Section 7. (first updated. 12.11.2020)

When one looks at the world rationally, the world, in turn, exhibits a rational element. The relationship is mutual. Understanding becomes indispensable even in areas where common opinion believes it to be least relevant. In other words, the “truths” that are commonly assumed to be correct are precisely the ones that understanding must challenge. Understanding, as a function of cognition, confronts commonly accepted views by presenting their inverse or opposite logical claims.

There exist truths—or facts—that are not immediately accessible to human understanding. These are furthest removed from what appears to be common sense. Philosophical inquiry, as a kind of science, aims to transcend ordinary conceptions of truth. It makes its subject matter the full range of possible logical claims, including their opposites. For any claim to be considered logical, it must be rational—meaning it must be conceived as a part within a whole, in which the parts presuppose the whole, and the whole presupposes the parts in a mutual structure of coherence.1

A philosophical system of thought offers the contrary to any immediately presented fact or opinion. The guiding question is always: What is the opposite of that? Understanding then seeks to find reason within this indeterminate process of thought. It does so by fulfilling two senses of the word “Reason”:

- First, the observer seeks reason as meaning or purpose—asking why mind or nature exists, for example, and attempting to uncover intentionality or direction in what seems to be a chaotic or random reality.2

- Second, the observer employs understanding to find reason as order—an attempt to structure the entropic disorder of existence into a system that is organized and intelligible.3

The term Reason, therefore, combines both purpose and order, each presupposing the other: purpose aims toward the achievement of order, while order constitutes the fulfillment of purpose.

Footnotes

The rational structuring of chaos recalls Kant’s notion of the understanding imposing form (categories) upon the manifold of intuition. See Immanuel Kant, Critique of Pure Reason. ↩

This reflects a Hegelian conception of logic and reality as a self-contained system where each part only has meaning through its relation to the whole. See G.W.F. Hegel, The Science of Logic. ↩

This is akin to the teleological understanding of reason, where phenomena are interpreted as having ends or goals. ↩

Defect of the Understanding

There are topics or truths that Hegel says are “furthest from the understanding,” meaning that there are aspects of our world that we do not understand at all. The absence of these truths in our grasp of reality is considered a defect of the understanding. As Hegel states:

“We can also gather that even in the domains and spheres of activity which, in our ordinary way of looking at things, seem to lie furthest from the understanding, it should still not be absent, and that, to the degree that it is absent, its absence must be considered a defect.”1

Hegel explains that the ordinary understanding of the world contains this defect because it falls short of achieving reason. This shortcoming does not occur by simply failing to arrive at reason—as though cognition were like locomotion, where arriving at a location means changing one’s position across a spatial plane. In such a case, arrival might be accidental rather than purposeful. But with cognitive faculties like the understanding, every mental act is done with intention. Nothing occurs accidentally in thought. Every “move” within the mental domain has some Reason or explanation that justifies its occurrence. In this way, understanding is self-explanatory—both because it provides its own justification, and because it appears as self-evident.

However, the understanding fails purposefully to reach the truth. This failure is not accidental, but intentional: it fails by misapprehending the data it receives from the world. It does so because it finds comfort in the limitations imposed by the senses—particularly perception. Perception, especially through vision, functions like a tunnel through which we experience the world in what seems to be its most “complete” format in terms of cognitive development.

Yet, the observer does not see the world in a complete way. Perception resolves the finitude of the observer by limiting the scale of reality. Reality, in itself, is indeterminate and potentially infinite. Perception compresses this vastness into a generalized picture (“general picture”), one that the observer can identify as a determined and familiar kind of experience.2 In this way, perception offers a manageable image of reality, but at the cost of completeness and truth.

Footnotes:

Hegel’s theory of perception, as developed in his Phenomenology of Spirit, highlights how perception abstracts from the infinite complexity of the real to create a stable, finite object of consciousness—thus concealing the truth of the thing-in-itself. ↩

G.W.F. Hegel, Science of Logic, §127. Hegel critiques the “understanding” for remaining within fixed determinations and for not grasping the dialectical movement of reason. ↩

Hermeneutic

The art of interpretation is natural—it is already performed by our senses. We interpret the world every day, effortlessly and continuously. However, our formal science of interpretation, hermeneutics, tends to limit “meaning” to the scholarly task of uncovering a thinker’s true opinion, as if that opinion is not already explicitly expressed throughout their body of work. Yet, we often feel that something fundamental is still missing in any major philosophical or scientific text. This persistent sense of incompleteness arises because truth is not static; it is continually being revised and rearticulated across different historical eras. What we call “interpretation” is, in fact, the enchantment—or advancement—of earlier understandings into new and novel frameworks.

However, this advancement of truth is not necessarily an enhancement simply by virtue of being new. Often, new interpretations convolute or even conceal the past rather than clarifying or revealing it. This is the first and most obvious observation in many contemporary works that claim to address “truth.” They either distort the past directly, by presenting fabricated or selective interpretations, or they obscure it indirectly by repeating narratives that have been formally accepted by consensus rather than by critical insight.1 In either case, the neutral observer is distanced from the truth—no matter what that truth may actually be.

It is worth noting that we are not concerned here with the practical science of translating one language into another. Even in such cases—where word-for-word translation may seem reliable—meaning is never fully preserved across languages. This is because words carry feeling, context, and lived experience, which are often culturally and even biologically specific. Certain meanings may resonate more deeply within specific groups due to shared epigenetic patterns—the expression of genes that change in response to environmental and social factors over relatively short periods.2

Humans, as a species, share the same sensory organs, acquired through evolutionary processes such as use and disuse. Through attention, we prioritize certain information over others. This act of selective focus is not random—it is driven by judgment, an ethical principle that underlies the very mechanism of understanding. Thus, the same faculty we use to interpret a subject is also the faculty we are trying to explain. In other words, we are attempting to describe the very mechanism we use to describe phenomena.

Footnotes:

Epigenetics refers to the study of changes in gene expression caused by mechanisms other than changes in the underlying DNA sequence. In this context, cultural and environmental conditions may influence perceptual and interpretive frameworks shared across communities. See: L. Jablonka & M.J. Lamb, Epigenetic Inheritance and Evolution: The Lamarckian Dimension. ↩

This critique resonates with Hans-Georg Gadamer’s Truth and Method, where he argues that historical consciousness is always mediated by our present horizon. The fusion of past and present often disguises itself as objective understanding. ↩

Generality

The notion of generality applies to the object in particular, in order to clarify a conception of it that unifies all its parts into a single coherent movement—one that can be tracked and traced by the observer. The generality describing a particular object outlines a mental or physical framework in which a set of differentiated components operate together, such that they exhibit a shared and fundamental characterization. A generally true conception of the mind, for instance, allows particular components to maneuver and function within a finite and discernible frame of reference.

This general picture, however, is not infinite or all-encompassing; it is finite and inherently limited. It is a generally true representation of a particular instance—not a complete account of reality as such. Perception thus resolves complexity into a “resolution”: the most complete picture of the most finite parts. Vision may give us the clearest image, but it is not the ultimate mode of conception.

The senses limit the world by providing an interpretation of it that is relative to the observer. In this sense, the sense organs become the true scientific subject matter of hermeneutics—the field concerned with interpretation in its most general form. While hermeneutics is commonly regarded as the individual’s interpretation of a text or piece of writing, perception itself is an act of interpretation: our senses do not deliver reality as it is, but rather as it appears to us.1

By failing to move beyond the sensory perception of the world, the observer constructs a “scheme” of reality—a conceptual framework within which they can operate, building their understanding from the “ground up.” However, in gaining access to a generally comprehensive picture of reality, something essential is lost. The observer misses the deeper essence of reality: the dimension that penetrates further into the structure of being, transforms it, and ultimately produces it in the first place.2

Thus, the understanding never fully advances to the reason it is supposed to achieve. Although the human being is said to be naturally endowed with reason from the start, paradoxically, he fails to realize it. Why is this the case? The failure lies not in a lack of capacity, but in the structure of understanding itself: it rests content with what appears, what is perceived, and fails to press onward into the rational, dialectical unity of what is beyond appearance.

Footnotes:

G.W.F. Hegel, in his Phenomenology of Spirit, critiques the understanding for remaining at the level of fixed distinctions and failing to grasp the dynamic, self-developing nature of truth. True reason, for Hegel, emerges only through the dialectical process that integrates oppositions into a higher unity. ↩

This view draws on Immanuel Kant’s insight in the Critique of Pure Reason, where he argues that perception is shaped by the a priori forms of sensibility (space and time) and the categories of understanding. What we experience is not the “thing-in-itself,” but the phenomenon as it appears to us. ↩

Obtaining Reason

Hegel writes:

“What is rational is actual, and what is actual is rational.”

Obtaining reason by way of the understanding is not like possessing an object, such as money. In this context, “having” reason means possessing a prerequisite for seeing things as they truly are. This does not refer to a simple realist approach that sees objects as they exist at a particular moment—an abstraction or snapshot of their being—but rather, to seeing them in their truth: as processes of development, as essences unfolding over time beyond any isolated moment.

The understanding is, after all, a rational faculty, because the world it apprehends is itself rational. As Hegel suggests (paraphrased): Reason is in the world in the sense that the world affirms a rational basis for our understanding. That is, when one looks at the world rationally, the world in turn reveals a rational element to that observer.1

The understanding often errs when it becomes unsatisfied with the content it is given—especially when that content is made up of ideas rather than feelings and sensations. Because the most immediate form of knowledge comes through sensory experience, the understanding initially struggles when it moves into the realm of abstraction. It becomes dissatisfied with substance it cannot “feel” or directly encounter. As a result, it confuses the material of the object it perceives as its true content, ignoring the underlying essence—the form or rational structure that determines the appearance of that object in perception.

Take shape, for example. Shape is a wholly abstract notion, because every object to some degree exhibits a unique, imperfect, and asymmetrical form. Perceived objects only roughly approximate certain abstract shapes. A table, for instance, may be called a square, but it is never exactly square. In fact, we recognize that there are no perfect squares in nature. There is always some minor variation—slight deviations in length, width, or angle—that separates the object from the pure, abstract concept of a square. These abstract notions, while ungraspable by the senses—unseeable, untouchable, untastable—are nonetheless always present in thought, either indirectly through intuition or directly through perception.2

While the understanding directly receives sensations from the world, it only receives the abstract indirectly and unconsciously—through thought. And yet, paradoxically, it is this indirect connection with the abstract that places the mind closest to the truth of things. The immediate objects of sensation, which the understanding is most familiar with, are often the furthest removed from the truest form of reality. We can support this claim by examining the rate at which thoughts occur compared to the rate at which experiences unfold. Thoughts arise at a much higher frequency in the mind, whereas direct experiences are slower, more prolonged. This suggests that thought operates in a more immediate proximity to reason, while sensation lags behind, tethered to the finite and temporal world of appearances.3

Thoughts occur immediately, while sensations occur mediately.

This means that thought arises directly in the mind, without needing a medium or external stimulus in the same way that sensation does. Sensation, by contrast, requires mediation—it depends on an external object, a sensory organ, and a process of reception and interpretation.

In other words:

- Thought is immediate because it is self-contained and self-reflective—it arises within consciousness without requiring an external cause. For example, thinking about justice or the concept of a square doesn’t require you to touch or see anything.

- Sensation is mediate because it depends on an external stimulus and passes through a physical medium (e.g., light, air vibrations) before it is processed by the sensory organs and interpreted by the mind.

Footnotes:

This echoes Hegel’s critique of sense-certainty in the Phenomenology of Spirit, where he shows that immediate sensory data is not the most reliable form of knowledge—because it lacks the universality and necessity of conceptual thought. ↩

G.W.F. Hegel, Preface to the Philosophy of Right: “What is rational is actual and what is actual is rational.” This phrase asserts the dialectical unity of reality and rationality—not that everything that exists is good, but that true actuality is imbued with rational necessity. ↩

Plato’s theory of Forms addresses the idea that perfect geometrical concepts, like the square or the circle, do not exist in the material world but only in the rational mind. See Republic, Book VII (the Allegory of the Cave). ↩

Relapsing into the “Sensuous”

When the human faculty of understanding does not “feel” the world as it does through the senses, it perceives the purely rational side of the mind as empty and void—as nothing more than representations of the world it perceives through the senses, which it assumes to be the “solid,” real world. The purely abstract dimension of reality is often experienced as terrifying, because it cannot be directly grasped. It is there as much as it is not there. Yet the mind, at any given moment, tends to see only one side without seeing the other.

A failure to reason occurs when the understanding, left to itself—without progressing to a rational synthesis—resorts to irrational conclusions, such as confusing sensuous experience with the full, self-consistent, complete totality of reality. At the same time, it reduces the abstract side of the world—occurring in the very mind that makes such a judgment—into a mere representation of something external to itself, as though it were dependent on that externality.

This is why what we commonly call understanding is more accurately described as a continued or developing understanding—not yet the full realization of Reason. It represents a developmental process through which the human mind attempts to understand itself by first interpreting its environment.

In this process, cognition becomes lost in the environment it perceives as external to itself. Consequently, the understanding concludes that since this environment is “outside” of itself, it must be superior, and what is internal—its own self-consciousness—is therefore inferior, merely a part of a greater whole.

The counter-intuitive insight, however, is this: the world we deem to be “full and complete” outside the mind is, in fact, the finite component, which is disclosed within the mind. What appears as a finite point within the environment—our own Reason—is actually the infinite element, making any perspective on the environment possible, regardless of how vast or indeterminate that environment may be.1

Science has consistently challenged the immediacy of how the world is given to the knower. It often proposes concepts that are furthest from what is immediately grasped through the senses. Yet these concepts are not inconsistent with the sensory world; on the contrary, they supplement and deepen our understanding of its most fundamental nature.2

Footnotes:

This tension between sensory immediacy and scientific abstraction reflects Immanuel Kant’s distinction between phenomena (what appears to us) and noumena (things in themselves). Scientific progress often occurs by abstracting away from direct experience, revealing deeper, often counter-intuitive truths. ↩

This echoes Hegel’s account in the Phenomenology of Spirit, where consciousness progresses through stages—from sense-certainty, to perception, to understanding, and ultimately to reason—gradually recognizing that what it takes to be external is in fact grounded in its own activity of thought. ↩

Common Sense

Science offers notions such as time and space, and rests on mathematical logic—such as geometry and units of measurement—as its foundation. These ways of understanding the world do not appeal to the senses; rather, they speak to the abstract capacity of Reason. Logical and mathematical concepts are neither felt nor directly experienced, yet they are applicable to, grounded in, and in fact constitute the very framework for all the objects that are felt, perceived, and experienced.

Hegel elaborates the problem with “common sense” in this way:

“But reflective understanding took possession of philosophy. We must know exactly what is meant by this expression, which moreover is often used as a slogan; in general it stands for the understanding as abstracting, and hence as separating and remaining fixed in its separations. Directed against reason, it behaves as ordinary common sense and imposes its view that truth rests on sensuous reality, that thoughts are only thoughts, meaning that it is sense perception which first gives them filling and reality and that reason left to its own resources engenders only figments of the brain…”1

Philosophy in modern times, even up to today, often operates as a reflective science. This means that it separates the world into categories—and maintains these categories as rigidly opposed to each other. In this way, the power of argumentation—i.e., rhetoric—becomes the central task of thinking, under the guise of being “reflective,” when in reality, it is reactive, often based on bias or partiality toward a one-sided position.

However, philosophy, in its true sense, is the love of wisdom (philo-sophia). It is more than merely parroting conflicting ideas in hopes of arriving at a rational conclusion. Philosophy is the science of truth, because it seeks essence. Therefore, the goal of genuine discussion—the dialectic—is to discover what things truly are, in any given instance. That is, the question becomes: What is the truth of this?

This is a more practical pursuit than the abstract desire to discover the “Truth” with a capital T—as if that meant uncovering the single truth above all other truths. In reality, the “truth of everything” is not some supreme truth hovering over particulars, but the ability to grasp the truth in each and every thing—the truth in any instance or situation. Common opinion, by contrast, knows the truth in the most limited and partial way—filtered through sensation, assumption, and inherited convention.2

Footnotes:

This recalls Plato’s critique in The Republic, especially in the allegory of the cave, where doxa (opinion or common belief) is contrasted with epistēmē (knowledge). Common opinion sees only shadows of truth, while philosophy seeks the essence behind appearances. ↩

G.W.F. Hegel, Encyclopedia Logic, §31. Hegel criticizes “reflective understanding” for remaining trapped in abstractions and dualisms, unable to grasp the unity of opposites that Reason seeks through dialectical movement. ↩

Opinion

Opinion is a judgment about a phenomenon that does not necessarily concern its essence—it is a superficial view.

An opinion is not necessarily false simply because it is an opinion—there are true opinions. However, an opinion is also not necessarily true merely by virtue of having one. What makes an opinion true as opposed to false is something outside of it. In other words, opinion always depends on facts external to itself. But even these so-called “objective” facts must be assessed as true or false by appeal to further standards or facts outside themselves.

Hegel clarifies the difference between opinion and reason:

“In this self-renunciation on the part of reason, the Notion of truth is lost; it is limited to knowing only subjective truth, only phenomena, appearances, only something to which the nature of the object itself does not correspond: knowing has lapsed into opinion. However, this turn taken by cognition, which appears as a loss and a retrograde step, is based on something more profound on which rests the elevation of reason into the loftier spirit of modern philosophy.”1

In this passage, Hegel outlines the process of forming opinion, which begins with an attachment to subjective truth—truth based purely on appearances. For example, when one sees an orange, opinion might conclude that what is seenexhausts what the orange is. It makes no effort to think beyond the way the object appears. Thus, opinion treats appearance as the totality of existence.

However, even though opinion is a limitation of cognition—often defined by bias and narrow-mindedness—it also serves as the starting point from which the observer must reflect and move beyond. Reason is born by negating this limitation.

Having an opinion is inherently limited because it assumes one side to be truer than another; otherwise, there would be no “opinion” at all, but rather a logical fact—a recognition that considers all relevant sides, whether equal or unequal. If “opinion” simply means choosing a position (true or not), and no distinction is made between true and false, then the very difference between truth and falsity collapses. Truth would become entirely subjective, resting on the will of the observer rather than on reasoned justification.

In such a scenario, there would be no standard for truth beyond the fact that someone holds an opinion. This undermines the very possibility of truth as something objective or rational, reducing it to mere assertion or preference.

Footnotes:

G.W.F. Hegel, Science of Logic, Introduction. Hegel often portrays the movement from mere opinion (subjective certainty) to rational knowledge (objective truth) as a dialectical process. Opinion is not discarded but is overcome (aufgehoben) in the development of reason. ↩

Appearance

Appearance and the Ascent to Conscious Cognition

Appearance is the starting point of conscious cognition because it serves as the avenue through which the observer begins the movement toward essence. This deeper elevation—from mere opinion to truth—is a transformation of mind: a rational state of grasping what is genuinely happening within any event or phenomenon.

The central philosophical question then becomes: Why is there a discrepancy between the truth of a phenomenon and the same phenomenon appearing to be false? The reality of any phenomenon is that it always contains its true, genuine self, as opposed to merely being a deception or false representation. Nature itself manifests both deception and truth simultaneously, and this complex interplay is expressed in the form of appearance. Appearance can thus hold both truth and deception at the same time.¹ Hegel speaks;

“The basis of that universally held conception is, namely, to be sought in the insight into the necessary conflict of the determinations of the understanding with themselves. The reflection already referred to is this: to transcend the concrete immediate object and to determine it and separate it. But equally, it must transcend these separating determinations and straightway connect them. It is at the stage of this connecting of the determinations that their conflict emerges.”²

Appearance, then, is not merely illusory—it provides the raw material and content that the observer must engage with and ultimately transcend. It is the initial form of truth, mediated by separation and contrast. Appearance separates the indeterminate state of nature into distinct objects, and maintains the differences of these objects against one another. This creates a structured world of contrast, where cognition begins by observing what things seem to be.

At this stage, the observer can either:

- Remain at the level of cognition where everything appears as isolated, irreconcilable difference—leading to confusion, contradiction, and disorientation; or

- Advance toward a higher synthesis, recognizing the contradictions as the very impulse of reason to go beyond them.

When understanding becomes “stuck” in the world of appearance, it regards contradictions as final barriers—paradoxes that suggest cognitive failure rather than deeper potential. However, Hegel warns us against this stagnation:

“This connecting activity of reflection belongs in itself to reason, and the rising above those determinations, which attains to an insight into their conflict, is the great negative step towards the true Notion of reason. But the insight, when not thorough-going, commits the mistake of thinking that it is reason which is in contradiction with itself; it does not recognise that the contradiction is precisely the rising of reason above the limitations of the understanding and the resolving of them. Cognition, instead of taking from this stage the final step into the heights, has fled from the unsatisfactoriness of the categories of the understanding to sensuous existence, imagining that in this it possesses what is solid and self-consistent. But on the other hand, since this knowledge is self-confessedly knowledge only of appearances, the unsatisfactoriness of the latter is admitted, but at the same time presupposed: as much as to say that admittedly, we have no proper knowledge of things-in-themselves but we do have a proper knowledge of them within the sphere of appearances, as if, so to speak, only the kind of objects were different, and one kind, namely things-in-themselves, did not fall within the scope of our knowledge but the other kind, phenomena, did. This is like attributing to someone a correct perception, with the rider that nevertheless he is incapable of perceiving what is true but only what is false. Absurd as this would be, it would not be more so than a true knowledge which did not know the object as it is in itself.”³

In this light, human understanding is often absorbed in what surrounds the subject—external sensations, mental effects, psychological impressions—without grasping the subject matter in itself. It becomes trapped in a shallow epistemology, mistaking attributes for essence. This is the mode of unconscious understanding, where the observer apprehends only the forms of things as they are given, rather than striving to uncover the inner logic of their being.

Footnotes

- Appearance and contradiction: This paradoxical dual nature of appearance is essential in Hegel’s dialectics. Phenomena are not merely deceptive; they contain within them the tension (contradiction) necessary for reason to rise beyond immediacy.

- Science of Logic: Hegel, Science of Logic, p. 43. Here, Hegel discusses the internal movement of concepts—how determination, division, and reflection generate contradiction, which then demands synthesis or resolution through higher reason.

- Critique of Kantian phenomenalism: Hegel critiques the Kantian idea that we can only know “appearances” and never “things-in-themselves.” He argues that such a division undermines the possibility of truth altogether, since knowledge divorced from essence is self-defeating.

Stimulus

Stimulus and the Limits of Understanding

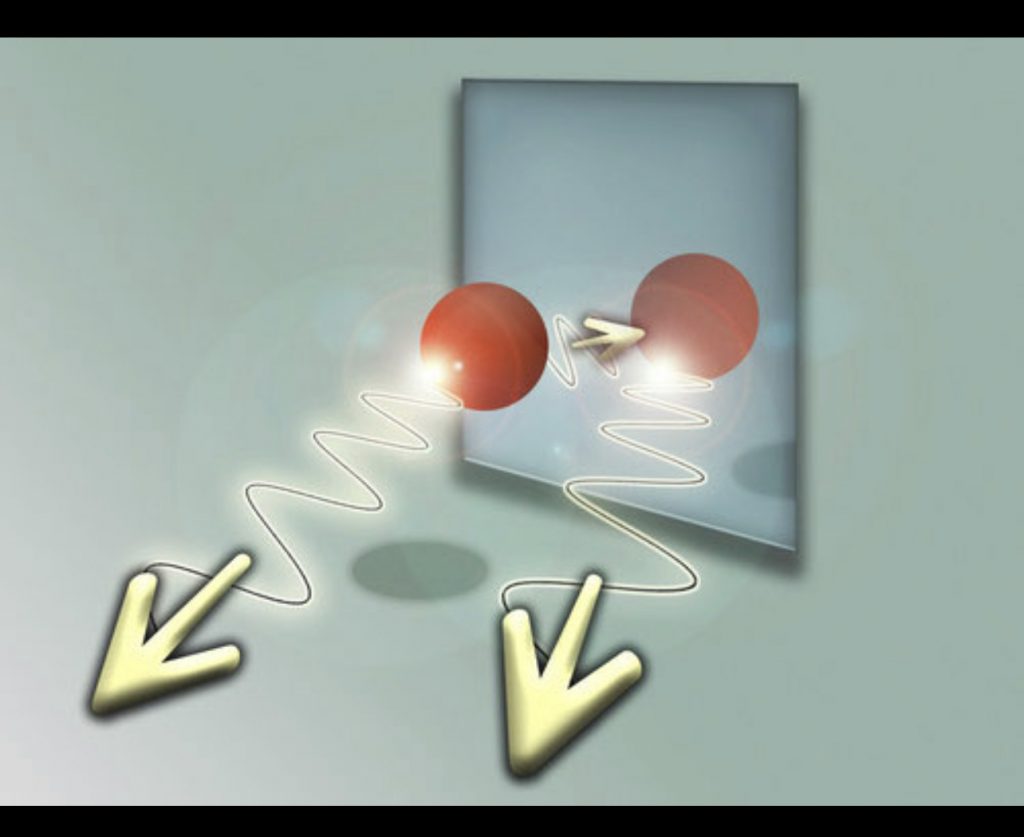

What it means to be a “stimulus” is defined by an event or an object that causes a specific reaction in an observer, whether consciously or unconsciously. In the unconscious sense, a stimulus causes a reaction in an organ. For example, in the process of cellular respiration, particularly during oxidative phosphorylation, the mitochondria—organelles within cells—use electrical voltage across their membrane as a source of energy to produce ATP (adenosine triphosphate).¹ The muscles then rely on this ATP as a source of energy to carry out various functions such as movement, tension, stretching, and contraction.

The moment an organ in the observer reacts naturally to a phenomenon, the reaction is known as a reflex, while the stimulus is the aspect of the phenomenon that triggered the reaction. In this way, the understanding is typically conscious of the objects that evoke a response; it places its focus on what stimulates it.

However, understanding is not well-equipped to grasp objects or phenomena that do not provoke a reflex. That is, it struggles to apprehend things that are present but are not sensed, felt, or registered in any immediate way. Yet, just because certain things are not noticed, does not mean they do not exist. These unseen or unfelt aspects of reality—though presently outside of direct perception—still exist. In fact, they represent the very goals that the understanding must work toward apprehending.²

In other words, cognition must be extended beyond immediate stimuli and reflexes, toward that which lies beyond sensation—the unfelt, the unnoticed, the unreflected—in order to become truly comprehensive.

Footnotes

- ATP and mitochondria: ATP is the primary energy currency of the cell, and mitochondria produce it via oxidative phosphorylation. The “electrical voltage” referred to here is the proton gradient (electrochemical potential) across the mitochondrial inner membrane, which drives the enzyme ATP synthase.

- Philosophical implication: This idea echoes the philosophical notion (e.g., in Kant and later Hegel) that phenomena (what appears to us) do not exhaust reality. There are aspects of the world—the “thing-in-itself”(Kant) or the essence (Hegel)—that are not immediately accessible to sensation or reflex, but which cognition must strive to grasp through reason and conceptual thinking.

Conscious in one respect – unconscious in another

The Dual Nature of Consciousness and Unconsciousness

While the understanding is conscious in one respect, it is unconscious in another. If we consider the total amount of time a human being has during a day, we might ask: Is a person mostly conscious or unconscious? The answer is more complex than it first appears. The intricate relationship between conscious and unconscious states is revealed through two apparent contradictions:

1. The Argument for Predominant Unconsciousness

If we assume that human beings are mostly unconscious, we are correct in the sense that the bodily operations—heartbeat, digestion, breathing, immune responses, etc.—function automatically and outside conscious awareness. Furthermore, a vast range of our actions are reflexive responses to stimuli we never consciously register. The total number of possible external events, internal sensations, and perceptual inputs far exceed the mental bandwidth of our conscious minds. In this light, we are only ever conscious of isolated moments within the full span of time; we experience punctuated moments of awareness, embedded within a broader, mostly unconscious temporal flow.

2. The Argument for Continuous Consciousness

On the other hand, if we assume that we are conscious most of the time, this also seems valid from a subjective point of view. I “feel” as if I am always awake, as though there is a continuous presence within my mind, even when I am not actively reflecting. There seems to be an underlying continuity—a kind of inner witness or “autopilot”—that sustains experience and action. We might call this an autonomous state of consciousness, or refer to it simply as the unconscious, yet it appears to be guided by a deeper, higher form of awareness that we are not ordinarily conscious of. This would imply the existence of a super-consciousness, one that governs the operations of unconscious activity without being directly perceived by the individual.

Collective unconsciousness

According to Carl Jung, the collective unconscious is the universal psychological inheritance shared by all humans—a reservoir of archetypes and primordial images that shape thought and behaviour.¹ It is present in each individual as the default state of cognition, prior to and beneath personal consciousness. However, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, a key figure in German Idealism, posits a state of consciousness even more foundational than Jung’s collective unconscious.² Though Hegel precedes Jung historically, his notion of Absolute Spirit or Absolute Knowing reaches further in describing the true essence of consciousness. For Hegel, consciousness develops dialectically, and the individual’s awareness is always part of a universal rational process unfolding toward freedom and self-realization.

Thus, we might say that consciousness has a “super” side—a collective consciousness—which, although not immediately accessible to individual awareness, nevertheless guides and determines the trajectory of unconscious states. This unknown conscious dimension of the unconscious steers the direction of human thought and action across time, shaping the future of the species.

Footnotes

- Carl Jung’s Collective Unconscious: Jung describes the collective unconscious as a layer of the psyche that contains inherited, universal symbols and experiences (archetypes). It operates independently of personal experience and shapes myth, religion, and instinctive behavior. See Jung, The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious.

- Hegel’s Absolute Spirit: In Phenomenology of Spirit and Science of Logic, Hegel argues that consciousness evolves through dialectical stages, culminating in Absolute Knowing—a state where subject and object, thought and being, become fully unified in self-conscious reason.

Warp

Any object is a stimulus in the narrowest sense of the word because it is the most concentrated form of the most general factors of nature. Any specific object is, by definition, the opposite of the generality formed by an uncertain number of possible objects. The opposite of indeterminate and confusing generality is a specific, particular, and peculiar thing. Thus, an object is the most particular and distinct aspect belonging to a more general factor known as a scenario or an event.

An event is, first, an indeterminate level of generality. Second, it becomes warped into a subset of specific configurations, appearing as shapes that trigger a response in the form of sensation—for example, seeing an object take on a three-dimensional figure. The most primary event that an object belongs to is a spherical form, which is why virtually every object in the world exhibits some degree of spherical magnitude.¹

A sphere is the first form of a three-dimensional figure because it is fundamentally a “warp” of spacetime, a self-sufficient and continuous form.² Yet we say that there can never be a perfect circle in nature, because in the natural world there is always flux, and flux implies change. Therefore, no perfect circumference of a two-dimensional circle can exist in three-dimensional space. This asymmetrical distortion of the circle is the phenomenon we observe in nature as a “warp”. Every object in nature has a dent or break in its form because its body is performing a specific function within a defined environment.

An object in nature does not move equally in all directions but is rather biased toward a particular direction. It “chooses” one finite path over others, and this selectivity causes the basic asymmetry in its shape. This deformation is necessary to meet the primary asymmetry of its purpose or determination.

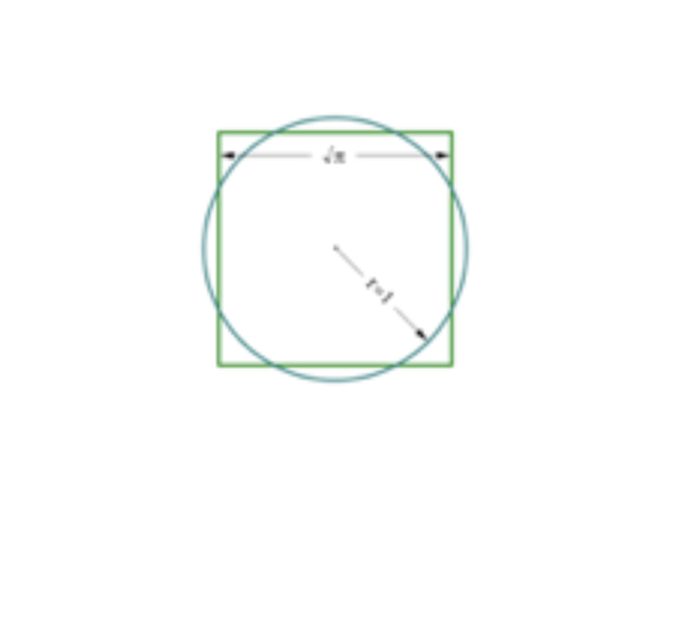

Squaring the Circle

There is archaeological evidence suggesting that ancient civilizations predating the Greeks made use of the golden ratio and practiced the principle known as “squaring the circle.” The Greeks are often credited for highlighting the mathematical problems associated with this concept—not for inventing it, but for formalizing its contradictions. While the Greeks and Babylonians produced sophisticated theoretical knowledge about the golden ratio, they left behind relatively little direct physical application of it. In contrast, even older lost civilizations appear to have physically implemented this principle in architecture and design.³

The Greeks formally defined “squaring the circle” as the geometric problem of constructing a square with the same area as a given circle, using only a finite number of steps with a compass and straightedge. They proved that this is mathematically impossible, due to the irrationality of π. However, this contradiction exists only within the realm of abstract mathematics. When applied physically, the “contradiction” functions instead as a tool of measurement. For the ancients, the perfect circle was not the end of mathematical reasoning, but rather the starting point—a reference form from which other measurements could be derived.

In the natural world, the perfect 2D circle is disrupted by the unknown dynamics of the third dimension. That is, 2D shapes become wrapped into 3D figures. Within this three-dimensional framework, unknown interactions—as described in thermodynamics by the law of entropy—introduce differentiation and divergence.⁴ This means that in any so-called perfect shape, a point along the circumference will deviate—not maintain uniform circular motion. It may diverge into a right angle, an acute angle, or even a singular point, forming a kind of “dent” or asymmetry.

This deformation can be visualized in phenomena like a raindrop, which is not a perfect sphere due to gravitational distortion, or in the dynamic shape of a flock of birds, which changes as direction and speed change. A wormhole, too, is theorized as a “sphere within a sphere,” stretched and folded within itself by intense gravitational forces—a literal warp in spacetime.

Footnotes

- Spherical symmetry in nature: The sphere is considered the most efficient shape in nature due to surface-area-to-volume ratio and isotropy. This is why stars, planets, bubbles, and even cells often approximate spherical shapes.

- Spacetime curvature and general relativity: Einstein’s general theory of relativity describes gravity as the warping of spacetime. A massive object like a planet creates a spherical dent or curve in the spacetime fabric.

- Squaring the circle and ancient geometry: While the Greeks proved that squaring the circle is impossible using classical tools, civilizations such as the Egyptians and possibly the builders of megalithic sites used geometrical harmonies—including π and the golden ratio—for architectural and symbolic purposes.

- Entropy and disorder: In thermodynamics, entropy measures the degree of disorder or randomness in a system. Any real-world system will tend toward greater entropy, which naturally disrupts perfect symmetry.

If we observe our most immediate environment, we notice that every object exhibits different shapes and varying degrees of figure. However, if we “go out” into a broader area of space—one that reveals a greater abundance of objects—we might assume that there would be more variability and diversity in shape and figure. Yet, quite the opposite is observed.

When we look out into the larger expanse of the universe, we find that the majority of objects—stars, planets, moons—share the same fundamental shape: the sphere. While the internal content within these spheres may differ greatly, the external form is remarkably uniform. It is only when we magnify these spheres, or enter within their circumferential frame of reference, that we encounter variations in other shapes—forms with edges and angles, such as triangles, squares, trapezoids, and so on.

This observation suggests that uniformity increases at a macrocosmic scale, while variability increases at the microcosmic or localized level.

The transformational motion of an event is an abstraction that captures a moment of change—a transition from one event to another. Crucially, the moment of change does not occur in the object itself, but rather within the observer, in relation to how the object is being conceived or interpreted.

To illustrate this idea, we can use the geometric figure of a trapezoid. The trapezoid, with its combination of parallel and non-parallel sides, can serve as a visual metaphor for temporal movement—a structure that demonstrates how time and motion can be described through changing angles and asymmetrical configurations.

Trapezoid

The “acute” determination—an abrupt movement or directional shift—transforms the circle into other shapes, such as a trapezoid, rhombus, triangle, oval, hexagon, etc. All these shapes, when experienced in a particular order or conjunction, and within a specific temporal instance, constitute the single common object we perceive. They are all planes or fields in which a spherical, discrete measure of a point can be disclosed at every dimensional magnitude.¹

The understanding, in the form of perception, selects from among these abstract shapes available in nature a particular combination to construct what we experience as a single object with a function. For example, a 2-dimensional trapezoid is fundamentally a 3-dimensional plane in conceptual terms. The latter is the functional expression of the former, but we experience this function as an abstraction, appearing to us as an object in motion.

First, the angles at the top of a trapezoid represent the furthest distance on that plane because they are the shortestand smallest from the point of origin of the observer. Second, the angles at the bottom form the largest length of the diameter, which is closest to the observer. This corresponds with common perceptual experience: things far away appear small, while things up close appear large—regardless of whether they are inherently large or small. For example, germs or bacteria, when viewed up close (e.g., through a microscope), appear relatively large.²

The trapezoid, then, is not simply a two-dimensional shape but represents a three-dimensional plane. Its form demonstrates a relative difference in extension—between a shorter and a longer side—unlike the square, which has all its sides equal in length. Among the most fundamental geometric shapes is the trapezoid. However, even more fundamental—not in a linear sequence of steps, but as an instantaneous structure that can appear at any momentwithin a sequence—is the square.³

Footnotes

Archetypal forms: Shapes like the square, circle, and trapezoid often function in philosophy and symbolic systems as archetypal or primordial structures—forms through which the material and conceptual world are interpreted (see Plato’s Timaeus, or Jung’s archetypal symbols).

Dimensional magnitudes: The notion of dimensions here follows both Euclidean geometry and philosophical interpretations of dimensionality (e.g., in Kant or Hegel), where spatial shapes are forms through which objects are structured and disclosed to perception.

Perceptual relativity: The phenomenon that things appear smaller when distant and larger when closer is part of basic optical perspective and is deeply embedded in how human beings intuitively process space and scale.

Even more fundamental than the square is the triangle, which holds primacy because it lacks a diameter yet still possesses three connected points, each converging at the center of a right angle. The triangle has fewer diameters than the square, but it remains a fully formed figure—a geometric structure that can be discerned from all sides. In other words, the four directional orientations (top, bottom, left, and right) can all be used to perceive the three points that construct the formation of a triangle.

The trapezoid, when condensed—not just by stretching outward, but by drawing inward—undergoes a transformation where the axes at each angle draw exponentially closer to one another. This motion causes the shape to collapse inward, while still preserving the trajectory of the diameter lines extending beyond it. The triangle is the moment of this transformation—the instant in which the trapezoid shrinks and resolves into a new configuration. It is a minute yet significant moment present in all objects, for it represents the dimension where change takes place, where one form gives way to the potential for another.

The circle, in contrast, represents a pure point of possibility—a field of indeterminate potential from which any shape or object may arise. This is because all the points along its circumference are equidistant from each other and from the center, and thus are equally prepared to shift into a new positional determination. However, when one point changes direction or form, it may not coincide with another point that has taken on an opposite determination—introducing divergence and asymmetry. The circle, then, is the ground of all transformation, the field from which determinations emerge and into which they return.

At the point inside the trapezoid, this transformation occurs as a kind of falling wavelength—a momentary shift in dimension, a ripple through space and form, which initiates the birth of a new shape or object.

The outermost acute angles of a trapezoid are directed away from each other, aiming toward the furthest possible point in opposite directions. Yet, paradoxically, the central point—situated perpendicularly between them and equidistant from both—is the nearest point where they may converge. As the common expression goes, “I can meet you halfway.” This midpoint allows the time and distance to be equally divided, so that both sides require the same effort to arrive at the destination.¹

The oval is one of the most fundamental forms within the family of trapezoidal shapes. It emerges after the relational unfolding of the circle, triangle, and square. The oval’s curved sides both move inward toward a central point, the nearest point furthest from the extremities of its curvature. The motion resembles the experience of falling off a cliff—a descent toward a gravitational center. This central motion converges at the radius, the point around which the entire plane enclosed by the oval’s circumference folds inward.

This converging center represents the core of a particular object—the entry point for perception to exit the current reference frame and pass into an infinitesimal dimension, where all possibilities are compacted into a single singularity. This singularity appears to be a point of infinite density, but in reality, it is an endless line—a wavelength—shaped like a tunnel. This tunnel contains every possible form, and every possible moment.

The understanding is unconscious of this dimension, but its existence is not negated by this lack of awareness. This infinitesimal location is simply “out of view” for the system of sensation. Yet, the understanding, which receives and interprets information from all sensory inputs, must eventually reflect back upon the world—a world where reason exists, and where all possible rational and irrational structures reside. This return is not merely for the sake of survival, but to determine what will construct the next sequence of events within the subset of a duration.

Footnotes

- Symmetry and Equidistance: This concept is used in both classical mechanics and metaphysics—especially in theories of equilibrium or symmetry—where opposing forces or forms resolve at a midpoint or center (cf. Leibniz’s notion of the pre-established harmony).

- Singularity as Possibility: The idea of a singularity as a compacted set of all potential outcomes echoes notions found in quantum physics (e.g., the superposition principle), as well as in metaphysical traditions like Neoplatonism or Jung’s archetypal unconscious.

- Infinitesimal dimension: This idea draws on the philosophical and mathematical notion of the infinitesimal—popular in Leibnizian calculus and contemporary physics—referring to a value so small that it approaches zero without ever being zero, often used in describing the transition between dimensions or states.

Sense-Certainty

Sense-Certainty: Object “Taken” as a Universal

Sense perception differentiates between objects; after each immediate conception of an object, the object is taken as a universal in order to maintain its certainty even when it is no longer immediately being perceived. The object itself cannot be taken as a universal, since even in perception the object is always changing, or the position of the perceiving subject shifts to disclose a different set of objects. In either case, the object is subject to continuous change and therefore cannot be held as a universal. Rather, it is something implicit within the object that must always be held as universal. The object contains within it our presupposition of the universal—that something remains unchanging. Even when we turn away from an object and direct our attention elsewhere, we still presuppose that something remains there, holding everything together. Thus, when we turn back, we assume that the same object will still be there, unless it has been acted upon by some external force. When the conception of the object becomes the universal of that object, the concept of sense-certainty is at work. This is not merely sensation itself, but rather a purely mental attribute. Sense-certainty refers to the assurance that there is something physical, regardless of whether it is currently present or not.

The problem with sense-certainty lies in its implicit assumption: while it correctly holds that there must always be something physical—since the sense organs are made to interact with the physical—it incorrectly assumes that this guarantees knowledge of what kind of physical thing is present. Just because we are always in contact with something physical through sensation, it does not follow that we can determine what specific physical object is present simply based on the capacity of sensation to register physicality. For example, one may say that there will always be a physical object in the future because there was one in the past and is one in the present. However, just because a dog existed in one’s past does not imply that one will encounter a lion in the future. Both are physical, both can be sensed, but they do not presuppose each other. Nor do they presuppose their own physical presence at times when they are not being perceived.

The universal of one object is maintained through the conception of another. At one moment, sense-certainty conceives of a tree and claims it to be “here and now.” But this “here and now” is lost when another object, say a house, is conceived. The previous “here and now”—the tree—becomes a universal in thought when the house is perceived, and the same occurs vice versa. One certainty disappears into the other, and when both objects are removed, what remains is the certainty that they were conceptions—that is, the self-certainty of consciousness is mediated through the negation of each particular object.

In this sense, the object is not excluded from thought but becomes its ground. Each object is encountered with the consciousness of that object, and this mutual relationship constitutes the object itself.

This universal process is mirrored in self-consciousness. When consciousness gains knowledge of the object, it can, in turn, produce the object. Art and technology, for instance, are the objects of consciousness that become objective in relation to other objects—they aesthetically develop the individual.^[1] (Recall that self-consciousness is the unity of consciousness and matter.)

The critical question then arises: How can the human being go beyond their enclosed subjective consciousness to understand consciousness beyond itself? This is the challenge that science seeks to address, and which philosophy has been grappling with since the inception of human thought.A flawed answer is offered by vulgar subjective idealism, which asserts that subjective consciousness itself gives rise to universal consciousness. In this view, one projects their own consciousness onto the world and claims that their subjective perception constitutes the universal. This is an empty claim: if your subjectivity were truly universal, it would not be merely subjective. And if it is only part of a universal that exists beyond it, then you have already conceded that your subjectivity does not account for the whole.

This subjective projection is the unscientific method of metaphysics, because it amounts to ignorance of what exists beyond one’s own consciousness.

It is valid to say that the world is infinite. However, postmodernists often conclude from this that the world is relative, meaning that no single standard holds authority over another within a system of order. But such a stance collapses the very notion of truth or objective knowledge.^[2]

Footnotes

(1) See Jordan B. Peterson’s critiques of postmodernism, especially his discussions on moral relativism and the loss of objective values in Western society.

(2) This reflects Hegelian ideas, particularly from Phenomenology of Spirit, where consciousness moves from sense-certainty toward self-consciousness and ultimately to the realization of Spirit through art, religion, and philosophy.

Judgement

The Human Being and the Faculty of Understanding

The human being is the first living organism that can explicitly be said to possess understanding. While animals do not turn their attention toward the world in order to question it, but instead accept it as given and operate within it, the human being develops the faculty of understanding, which allows for the act of judgment.

Understanding operates through analysis, which is the mechanism of abstracting a conception into a particular entity and examining it as such. This explains why judgment is inherently limited—because it works by isolating aspects of a whole and evaluating them in abstraction.

Judgment places the observer in the position of the object. To pass judgment on something is to abstract the mind from the self and direct it toward the thing in order to experience it as it is. Judgment is therefore fundamentally an ethicalact, because it involves the intention to know the object in itself, regardless of whether that knowledge is successfully attained. The act of judging arises from the ethical intention to know.

Whenever the understanding encounters a new system of ideas—such as a belief—it immediately passes judgment. In this way, understanding is rightly called the “faculty of judgment,” not because it is merely analytical in the sense of being neutral or objective, but because it is also normative. It judges, ignores, selects, gathers, and formulatesinformation. And since it is ethical in nature, it is also unethical—it can err, be biased, lazy, sluggish, ignorant, arrogant, and more.^[1]

Impartiality always remains an ideal for the understanding. It is not a quality found at the beginning of the process but is something to be achieved only after filtering out the biases that enabled the information to be received in the first place. Seeking knowledge “as it is” can only happen after it has first been received in a biased way. Thus, whenever the understanding hears a new idea, it critiques it—because it is naturally ignorant or uncertain of the truth. This is why it seeks to either gain or confirm knowledge.

For example, when we encounter belief systems such as Jehovah’s Witnesses or Mormonism, we might immediately dismiss them as laughable or irrational. However, even within these systems, there is some truth: people use them to live, to make sense of their experiences, and sometimes even to find a form of enlightenment.^[2] The presence of any truth in such beliefs forces us to reflect more deeply: if these systems contain truth that we initially ignored or dismissed, then how much do we really know about Truth itself?

Footnotes

- Kant refers to understanding as the faculty of judgment in his Critique of Judgment. While he often treats judgment as a power for subsuming particulars under universals, your treatment emphasizes the ethical and fallible nature of this process, which aligns with certain existential and phenomenological readings.

- William James, in The Varieties of Religious Experience, emphasizes the practical and psychological truths found in religious belief systems, regardless of their metaphysical correctness.

Organs of Understanding

The special function of the organs is the natural means of the understanding.

The understanding is not merely a theoretical framework that the observer constructs in order to conceive a general view of reality. Rather, a general view naturally arises through the cooperative functioning of various cognitive faculties as well as the coordinated efforts of the sensory faculties—touch, sight, hearing, thought, and so on. Together, these faculties provide the picture of the world that is taken for granted by the observer. None of these faculties can function in isolation; each depends on the coexistence of the others.

Consider the question: Can a blind man still hear? The answer is yes, but not in the same way as someone who possesses both sight and hearing. Even hearing, when it is not accompanied by sight, is still supported by other faculties such as thought and reason. In fact, this raises a deeper question: Can a man with no senses at all still reason? If the senses do not provide him with a world to reason about, what is he left with? Can he truly reason about his own reason without the content that reason needs—namely, what the senses provide?

This question is theoretical and abstract, disconnected from concrete reality. In theory, we may attempt to separate reason from the senses, but in reality, such a separation is an artificial move made by the understanding itself, operating through abstraction to better comprehend its own workings. However, the understanding becomes trapped in these abstractions, failing to see that reason and the senses are essentially of the same substance.

For example, the senses are not external to reason but are extensions of it. They are the instruments through which reason develops in order to understand the world. To claim that the senses operate independently and then provide input to reason is to fall into the very fallacy that the understanding uses to get a grasp of the world—namely, the mistaken belief that reason is separate from the world, rather than recognizing that the world itself functions as an extension of reason.

In other words, reason extends itself outward, manifesting as those organs we believe give rise to reason in the first place. They are, in truth, not separate. Reason and the senses are unified, and while we must make conceptual separations in order to study and understand them, we must also remember that they are ultimately parts of the same whole.

Hegel says:

“Interpreted in this way, then, the understanding manifests itself everywhere in all domains of the objective world, and the “perfection” of an object essentially implies that the principle of understanding has its due therein. For example, a State is imperfect if a definite distinction between estates and professions has not yet been achieved within it. Similarly, a State remains imperfect if the conceptually distinct political and governmental functions have not yet formed themselves into particular organs—just as in a developed animal organism, the various functions such as sensation, motion, and digestion are differentiated into specific organs.” (Hegel, 127)1

Hegel argues that understanding (or rational structure) is present throughout the objective world. An object or system is considered “perfect” when it fully embodies this rational structure. For example, a State is imperfect if it lacks clear distinctions between social roles (like estates and professions) or if its political and administrative functions are not properly organized into distinct institutions. Just as a biological organism becomes fully developed by assigning specific functions (e.g., digestion, movement) to specific organs, a State becomes perfected when it organizes its various functions into specialized institutions or bodies. This is part of Hegel’s broader philosophy of organic unity and rational organization. He draws an analogy between:

- A living organism, where each organ has a defined function (like the heart for circulation, stomach for digestion), and

- A State, which is “alive” in a similar way when it functions as a whole through differentiated but integrated parts.

In both cases, “perfection” means that the parts are not just present, but functionally distinct and coordinated, guided by an underlying rational order. This reflects Hegel’s view that the actualization of reason in reality is the highest form of development—whether in nature, society, or politics.

Perception as the “Lightest” Contact

The ancient Atomists observed that perception is the lightest form of contact. They accounted for perception and all other sensations by means of contact. For example, sight occurs, according to this view, when a thin film or image (eidolon) detaches from the surface of atoms and makes contact with the sense organs.2 Atomists like Democritus, being strict materialists, used this theory of contact to claim that all phenomena, including perception, are mechanical interactions. Thus, they denied the possibility of pure abstract knowledge.

Ironically, however, their explanation inadvertently demonstrates that matter itself contains a degree of abstraction measurable by the level of contact. If contact is a measure of knowledge, then the greater the contact a sense organ has with its object, the more concrete the knowledge. By that logic, something hard would be more concrete than something soft. Consequently, perception would be considered the least concrete of the senses.

But this is not necessarily the case. All forms of texture and density are equally experienced as concrete, and perception—particularly visual perception—is arguably the most developed and valuable sense for the understanding. Perception, as the “lightest” form of contact, is also the most abstract. It proves to be the most refined form of sensation for cognition because it offers the most general overview of the object. Sight allows for the apprehension of universal characteristics such as color, shape, and motion—fundamental categories of appearance. These abstract, general forms make vision uniquely suited for conceptual thought and understanding.

Footnotes

In Atomist theory, particularly in the writings of Democritus and later Epicurus and Lucretius, eidola or images were thought to constantly emanate from objects and strike the senses, producing perception. See Lucretius, De Rerum Natura, Book IV. ↩

G.W.F. Hegel, The Philosophy of Nature, trans. M.J. Petry, vol. 2 of Encyclopaedia of the Philosophical Sciences(London: George Allen & Unwin, 1970), 127. This passage is drawn from Hegel’s exploration of the organic body and the concept of “organs” as differentiated functions, both biologically and politically. ↩

Aether is Gravity

Aristotle brings in the “fifth” element called “aether,” which is really the “first” element because it is more fundamental than air, earth, fire, and water. Plato calls aether the “most translucent kind.”¹ Aristotle explains that it is neither hot nor cold, neither wet nor dry.² Aristotle never used the word aether when introducing the element in his work On the Heavens,³ unknown because it is imperceptible, but that word became associated with what he described as a substance only capable of local motion—that it naturally moved in circles and had no contrary, or unnatural, motion. In other words, it is pure motion.

In modern times, aether is dismissed and said to be non-existing, but really what is dismissed is the word, and not the concept it denotes, because the concept Aristotle was describing is what we know today as gravity. Gravity is also not obvious in how it is present in space and time. Some scientists claim that gravity exists as a force that holds everything together. However, basic observation suggests that everything already appears to be held together on its own. Therefore, it may seem that no deeper thinking is required to discern the concept of gravity beyond what is already evident to perception. All things appear to be in place and move in harmony with one another.

If gravity is the force that facilitates this process, then it should not be abstracted as a separate or isolated force. Instead, it may be understood as the collective, simultaneous, and instantaneous motion of all objects in relation to each other. Every object is constantly in motion, interacting with every other object in a unified, harmonic manner. And yet, we still feel that gravity must be described as its own force—something acting externally on something else. The external relations between objects form structures in spacetime, and it is these structures in spacetime that Einstein aims to describe in his theory of gravity, which is the closest idea we have today of what it truly is. Although it is still wrong.

Deeper than that, gravity is the events in spacetime itself—which Einstein, in only describing the physical structure, obviously overlooks—the soul, the essence of that matter.

Elaboration on Gravity:

Gravity is one of the four fundamental forces of nature, alongside electromagnetism, the strong nuclear force, and the weak nuclear force. According to classical physics, particularly Isaac Newton’s law of universal gravitation, gravity is the attractive force that acts between any two objects with mass. This force explains why objects fall to the ground, why planets orbit the Sun, and why galaxies form. Gravity is literally the “in-between” of celestial objects.

Einstein’s theory of general relativity expanded on this by describing gravity not as a force in the traditional sense, but as a curvature in space-time caused by mass and energy. According to this view, massive objects like Earth warp the “fabric” of space-time, and smaller objects follow the curves in that fabric—what we perceive as gravitational attraction.

Gravity may not feel like a “force” in the way we experience, say, being pushed or pulled directly. Instead, it manifests as a continuous, holistic interaction—everything influencing everything else, constantly. In this sense, gravity can be seen as a global relationship, not merely an isolated interaction between two objects.

While modern physics models gravity as a calculable force (or curvature), it’s true that its effects are emergent and interconnected—objects indeed move in relation to each other in a way that seems almost choreographed. This does not mean gravity isn’t “real” or requires no explanation, but rather that our understanding of it continues to evolve, especially as we venture into quantum physics and theories of everything.

Attraction and Repulsion

Gravity is most primarily described as the affect that objects have on each other. Objects exhibit different size, weight, density, etc., and these differences in their quantitative measure have an effect on how they attract and repulse each other. The greater the weight, size, or density, the greater is the force of attraction. Attraction is not always the same in different dimensions. The dimensional magnitude, i.e., the size, for example, manipulates the relation between attraction and the next moment when that attraction turns into repulsion. Attraction and repulsion are not external forces; they both belong internally in each object that is external to another. The object is external from other objects exhibiting these forces in certain unequal ways, and so we mistakenly assume that when attraction is happening between two objects in the vacuum of space, repulsion is happening somewhere else. However, repulsion and attraction are degrees of the same force taking on opposite determinations.

When two objects attract each other with a great force—meaning that when one object attracts the other faster—the opposite inverse force of repulsion propelled by the object being attracted is equal to the volume of its size, density, weight, etc. In simpler terms, the position that the body occupies in the fabric of spacetime is the same force that causes the object to move away in relation to the bigger object moving toward it. In gravity, you have this static position, this lack of motion, between all objects that maintains their differences. We cannot have direct observation of this hidden force, because it is by very nature indirect; it is the positional change that is the causal source for a stable conception of related objects. Aristotle already called it the “unknown” celestial body.

We ascribe Isaac Newton as being the “father” of inventing the idea of gravity because he outlined the basic mechanics of it, but the idea of gravity as a general notion has been present since Ancient Greek times. In the Modern era, Einstein revolutionized the idea of gravity with his notion of spacetime—that gravity is the warping of spacetime— that spacetime is the structure of the cosmos.⁴ Gravity is a change that is observed in the “fabric” of spacetime. The problem is that we do not know whether that change is caused externally by an unknown factor, or whether there is an unknown internal force of change. The notion of gravity is still imbued with this paradox.

Footnotes:

- Plato, Timaeus, 58d–59c – where he describes aether (or the fifth substance) as the purest and most divine element.

- Aristotle, Meteorologica and De Caelo – discusses the characteristics of the four terrestrial elements and the fifth (unnamed) celestial substance.

- Aristotle, On the Heavens (De Caelo), Book I–II – introduces the fifth element without naming it aether, describing its natural circular motion and incorruptibility.

- Einstein, Albert. General Theory of Relativity (1915) – proposes that massive objects cause spacetime to curve, and that gravity is this curvature rather than a force in the Newtonian sense.

Spacetime is complex yet simple

Spacetime is very complex, yet at the same time, it is also very simple. Terms like “complex” and “simple” have physical meanings—i.e., they represent different degrees of physicality.

Spacetime is complex because it contains all possible content in the universe, including different dimensions of past, present, and future, and all levels of physical magnitudes. Yet it is still simple because it possesses no quantitative measure, only a mere qualitative explanation. In other words, it is the most basic and primal physical substance. This means that the essence of spacetime can be conceptually described and demonstrated, but it cannot be measured in terms of solidity, plasticity, size, weight, etc. It is the rarest, fairest, lightest—or in other words, it is the most abstract substance in the known universe. This substance corresponds with “reason” as a fundamental essence in the universe.

Spacetime is not the conjunction of space placed together with time. The basic placing of the words together in conjunction denotes an altogether different topic than if we subsume space and time independently as distinct principles. Space on its own is the abstraction of having a context, a place, or a position where an object can reside. However, space is distinguishable from the object, while at the same time is not distinctly any specific kind of object. Space is not like one object contained by another—e.g., like the embryo within the egg or the cream in the donut.

Space, in this sense, is akin to gravity—except that while gravity may be an active force caused by a cavity or distortion in spacetime, space itself is passively absent. Both represent abstractions in the substance of spacetime, but one is active and the other passive. These subtractions are what we describe as different concepts—emerging from a deeper breakdown of fundamental substances. Space remains universal because it is the abstraction of having these distinct forms sharing the same conception. In other words, the different aspects we pick out in space and call “objects” belong as components of space as much as the concept of space belongs as a component of any picked-out object.

Time on its own is an occurrence—or rather, an event—consisting of differing forms. But objects in time do not necessarily share the same context of space. An event may have happened years ago that relates to the present moment. Two or more entirely different events can occur in what otherwise appears to be the same location. Conversely, similar events—like giving birth, eating, or passing—can occur in entirely different locations.

Spacetime requires that space be made indivisible from time, and vice versa, while maintaining their distinct qualities. This would “look” something like this:

- Space is the context for any series of variables relating to form an event that occurs in a single context of the same place.

- Time is the difference of these variables occurring—each having their own space and context to occur within—while sharing a general moment and location of space. The moment is the quality of time that each present object has that distinguishes it.

So, you can have a bee flying around a boy’s head—both the boy and the bee share the same space, but the bee is within an entirely different dimension of spatial magnitude as compared to the boy. This means that every possible moment of time takes on its own context of space, while space contains the infinity of all these moments taking on a unique series in time.

Totality of Spacetime

Einstein explains that the totality of spacetime has an effect on each object within it, but also that individual objects have an effect on overall spacetime proportional to their size, weight, force, etc.¹ This means that the object taking on a place in space is also a happening. The word “object” describes the physical reference frame that captures events within its boundaries. The essence of an object is an event, because it is an animated force of motion that is quantified by size, density, heat, light, etc. All these qualities of the object reach a degree of limit in space, and it is this limit that has an indivisible connection with another object. In other words, the total variables that go into an object fill up the space it resides in, reaching an outer limit that locks with the outer limit of another object—and both have an asymmetrical gravitational bond with each other called an “orbit.” Einstein introduces spacetime by describing the mechanics of it, but he does not clarify the essence of spacetime.²

The explanation that spacetime is a plane of three-dimensional time and one dimension of space is limited in explaining the essence of spacetime. For one thing, Einstein was somewhat against quantum mechanics because he viewed the theory as unpredictable at the macroscopic scale.³ Although it describes nature at the atomic level, he did not view it as a useful basis for all of physics. Einstein apparently valued firm predictions followed by direct observation, and he famously claimed that “God does not play dice,”⁴ expressing his ontological position that the universe is stable, predictable, and governed by determined laws of nature. Today we think quantum mechanics contradicts Einstein’s theories of spacetime, but in truth, it actually reveals and explains what it is. Einstein did not like quantum mechanics because it resolved his theory—and he wanted to maintain the perplexity that marked the limit of his knowledge.