Quantum Preliminary; medium vs. process

Quantum mechanics has recently shown that reality ‘is not what it seems’—that classical mechanics do not constitute the absolute framework for the fundamental operations of nature. This recent discovery is not new in the realm of philosophy, as it has been established since the beginning. There is a recurring theme in the cycle of history, where philosophers always challenge the world as it appears to the senses.

The conclusion is primarily always the same: the fundamental substrate of matter does not provide the essential framework for nature. There is, instead, a mind behind it. But it is only now that we have an empirical view and direct evidence through observation that classical models of physics constitute only part of nature’s operations. It is almost absurd to ask about the existence of something that is “already-there,” and yet this is our task in the sciences, as Hegel says:

“This apprehensiveness is sure to pass even into the conviction that the whole enterprise which sets out to secure for consciousness by means of knowledge what exists per se, is in its very nature absurd; and that between knowledge and the Absolute there lies a boundary which completely cuts off the one from the other. For if knowledge is the instrument by which to get possession of absolute Reality, the suggestion immediately occurs that the application of an instrument to anything does not leave it as it is for itself, but rather entails in the process, and has in view, a moulding and alteration of it. Or, again, if knowledge is not an instrument which we actively employ, but a kind of passive medium through which the light of the truth reaches us, then here, too, we do not receive it as it is in itself, but as it is through and in this medium. In either case we employ a means which immediately brings about the very opposite of its own end; or, rather, the absurdity lies in making use of any means at all.”

Hegel makes an early recognition of the observer-phenomenon problem in quantum science. In the above paragraph, Hegel provides the earliest account of quantum mechanics that we can directly link to Modern scientific thought. Before we explain what Hegel is trying to say in the above paragraph, let us first explore the context of his assertions. The dilemma in science, and the one that puzzles quantum science today, is the relationship between the “observer” and the “phenomenon.” In other words, how each influences the other in order for both to create each other. The observer and phenomenon maintain each other as opposite interactions of a determination, but how do they maintain each other? In what way do they influence one another, and what is the role of each in the components making up the interaction?

Hegel discusses how a process passing through a medium is ultimately changed by virtue of passing through that medium. In other words, any process passes through a “medium” or a dimension that enables it to be transmitted. However, in this transmission—whether it’s a natural object growing into its full potential before degenerating into its opposite, or a process like speech transmitted through a telephone—the medium plays a role in altering the process. Whether it’s an internal process like natural growth or an external process involving the interaction between two objects different from each other in time and space, in either case, it seems that the medium (the instrument) has an active role in changing the process. The process is not left as it was before it passed through the medium, but instead, the medium imparts to it a quality that works consistently with the being to which it is transmitted.

For instance, in the transmission between any two objects, even if the source is the same as the receiver, the process is designed in such a way that the receiver can apprehend it. This is similar to the way magnification works: the instrument zooms into a small area, making it “appear” larger to the human eye. In other words, the magnifying glass alters the dimensions—distances, size, etc.—to bring one part of the object forward and push another away, so that the eye can better understand what it is perceiving.

Observer “dilemma”

The effect the observer has on the phenomenon is defined by the role of knowledge as a medium for truth. For something to be a “medium,” it has two meanings. First, in more physical terms, a medium is a passageway that allows things to pass through from one source to another. In this sense, a medium does not affect the objects passing through it; it simply acts as a passive conduit through which the transition takes place. Secondly, a “medium” refers to a relation—it is what maintains two separate things in unity. In this sense, the medium does not leave the objects as they are; rather, in the process of transferring, they are changed or influenced by the medium itself that facilitates the passage.

The dilemma surrounding the observer concerns what it means for a phenomenon to exist in and of itself, and how it bears a relation to an “other”—either to itself or to something that is not itself.

Hegel says that whenever the mind determines an aim into existence, it always brings about the end opposite to the intended meaning. The intent is one way, but the result is never exactly as intended.

The observer “employs a means which immediately brings about the very opposite of its own end.” How does the observer affect the phenomenon? First, the very task of trying to secure for consciousness knowledge of what exists per se is, in its very nature, absurd. There is a boundary between the observer and the phenomenon that cuts off one from the other. If the observer is the way to gain access to the phenomenon, then the application of the observer to any phenomenon does not leave it as it is for itself, but rather entails a molding or changing of it in the process. On the other hand, if the observer is not the avenue through which an alteration of the world is actively employed, but the phenomenon is the kind of passive medium through which the light of truth reaches the observer, then here too, the observer does not receive the phenomenon as it is in itself, but as it is through and in this medium.

Limitations of perceiving time

Time is as much a mental principle as it is a physical one. This means that “events” happen to the mind, and they are the future or the past of the present moment, belonging to an observer. There is no direct evidence of time in the sensible sense; for example, you cannot see time in the same way you see space, because you cannot directly observe the degeneration or generation of objects. Instead, you only witness moments of time. When you directly observe anything in the universe, you are witnessing an abstraction of time, which is that object during a particular moment in its overall timeline. No single observer can see what happens throughout the total duration of time. The duration of time happening to one thing is disproportionate to the duration of time happening to another.

The observer only ever sees the object at a particular instant. For example, the duration of time for a human observer is mediated by opposite extremes of temporal magnitude. Either the time duration is too fast, and a human cannot catch it, or the time duration extends far longer than the observer’s lifetime. For example, the lifespan of bacteria or atoms is too rapid for a human to perceive the total number of events that occur within that duration; conversely, the lifespan of stars is too vast and long for a human to ever witness the beginning and end of that duration.

In this way, the observer can never see the full amount of time happening to any particular object, but only discrete moments that constitute one point within a timeframe. Furthermore, whenever the observer encounters any occurrence in daily life, he either arrives before it has happened, after it has occurred and witnesses the aftermath, or he happens to catch the moment as it occurs. However, during the occurrence itself, it is too variable for the individual to fully apprehend what has transpired. It is only through reflective reasoning that the individual can determine a proper understanding of an event that occurs in time. The individual can also “plan” or determine an event towards a result he wills. If he reasons before an event and initiates it, how well will the true actuality of the event align with his prior intuition about its potential? This question is not fully known and inherently exhibits an uncertainty principle. This is, in essence, what uncertainty is.

Difficulties facing quantum science

There are certain difficulties that quantum science faces that are similar to those metaphysics have faced in the past. Namely, in the last few decades, quantum science has been threatened by misinterpretations that introduce mystical dogmatism into the field. That is to say, the term “quantum” is so loosely used nowadays that laypeople apply it to make supernatural or grandiose claims. This is the same critique aimed at metaphysics, which is often reduced to the term denoting a world beyond physical matter.

Certain kinds of thinking have used this allegation of the term as an excuse to discuss matters that would otherwise be unsubstantial in the realm of logical and empirical demonstration. The ambiguity that accompanies quantum science has produced fear in empirical scientists, halting them in an intellectual dead-end of seemingly deducing limited facts. However, if we look back at the history of our recent technological development, we can finally understand the reason behind it. Since the start of the 20th century, humanity has focused on the development of computers and the gathering of facts that characterize their function. People have been endlessly collecting facts and information online without a clear reason, only to share and capture the attention of consumers. However, the development of this vast body of information is now the intent being used by the next era of computer development—AI, or artificial intelligence.

Man, as a natural being, generates knowledge, but he lacks the ability to form it perfectly, because he is imperfect. On the other hand, the mind of artificial nature cannot generate anything from its own self but can only reify the generation of things that have been arrived at naturally. However, it has the power to assemble and form that information into a coherent, perfectly logical resolution for a natural being, like man.

World Historical Individuals

Time only exhibits itself as discrete moments and events. Modern science depends on ideas from previously established human inquiry. However, even with the ability to look back into history, modern thought, whether purposely or accidentally, fumbles in formulating a conclusive idea of the past. Academics piece together a complete timeline belonging to a period in history by arranging fragments and scattered events, which we call pinnacle moments. However, these “pinnacle” moments are what Hegel refers to as “revolutions” or “changes” in history, caused by “world historical individuals.”In Hegel’s philosophy, “world-historical individuals” refer to exceptional figures who, through their actions, embody and propel the movement of history. These individuals are not merely personal figures; they are representatives of larger historical forces or ideas that shape the course of events. They act as catalysts or agents of change, pushing history forward and helping to unfold the rational development of the world spirit (or “Geist”) in time.

These “world” individuals, although often miserable, selfish, and greedy, have “passions” that coincide with the next step in the development of history as a rational process. The “passions” of certain individuals in history act as catalysts that mobilize the passions of the general masses at critical points in history.

Hegel believed that history unfolds according to a rational process, and world-historical individuals are those who, through their unique abilities, passions, and actions, play a crucial role in advancing this process. These individuals are often seen as driven by strong personal motivations—such as ambition, desire, or vision—but their actions often have a broader, historical significance.

Examples of such world-historical individuals in Hegel’s view include figures like Alexander the Great, Napoleon Bonaparte, and Martin Luther. These individuals, in Hegel’s philosophy, are not simply “great men” in a personal sense, but rather the embodiment of historical necessity, carrying out their roles within the unfolding of world history.

Ultimately, Hegel viewed history as a rational process of development, and world-historical individuals are essential to this progression, even though their actions may seem, at times, driven by personal or seemingly arbitrary motivations.

Misapplying History

Academics focus on preserving past “historical” ideas, but they overlook the fact that, in the process of interpreting them, they oversimplify them into straw-man notions. This happens because the mind will always understand a “concept” only to the limited degree of its own capacity. The level of development of the mind making the interpretation corresponds to the level at which the concept is understood. For example, a grade 1 student will understand a concept in a grade 1 way.

These overly simplified concepts of ancient times are passed down to students, making them feel like they understand the concept. However, there are a few keen students who realize not only that they do not fully understand what is being taught, but also that what is being taught is not even fully understood. What is often overlooked when interpreting thinkers of antiquity, like Plato and Aristotle, is that their notions of Being are profoundly more complex and sophisticated than what is usually granted to them. To this day, their ideas are still not fully understood.

Modern thinkers operate under the assumption that, as time ascends forward, ideas become more complete and complex. However, if we look at how history unfolds, we notice that all major civilizations reach a “peak” of evolution and then ultimately collapse. In this view of history, development is cyclical. This means that the highest peak of development in knowledge is NOT found at the end of a civilization’s history, but rather during its peak, which can be anywhere in the middle or even at the beginning of its timeline. Hence, the present cycle of history may look back at the past and see a collapsed civilization, assuming that because their time has passed, it was more primitive than the current time in history. But what the observer fails to grasp in this abstraction is that the present moment, from where they are making the interpretation of previous ideas, may be at a lower stage of development compared to the period they are interpreting. For example, an adolescent may think of himself as more complete than an older adult because his brain is fresh, but what he does not see is that the adult has gone through more experience and is at a higher level of intellect.

History moves forward toward an extent point of development, much like, analogously, a tree will extend its branches towards the furthest point in space. We do not know the full extent of history’s ultimate development. When we look back at past civilizations, we see the remnants of a lost society in time. How long their remnants withstand the test of time can correlate to the level of development they had reached.

However, there is a trick: the older the civilization discovered to be, the worse the condition of its artifacts. The worse the condition, the more it creates the assumption that they were less developed than they actually were. In other words, their artifacts look more primitive the older they are. However, this primitiveness in technology could be a result of the artifacts being fossilized into stone. If you leave out any object, even metal objects or living organisms, over enough time, they fossilize and turn into stone. We see the material and assume that it was the same during their present time. What we fail to realize is that the material of the artifact itself has changed over the span of time.

It could be the case that during the peak of ancient philosophy, they had already answered the questions we are asking today with the recent science of quantum mechanics. The same issues in quantum mechanics are the subject matters of metaphysics, just viewed in a different light. In fact, their ideas are so developed and complex that a demonstration using the physical sciences, which underpin modern thought today, may suffice as the next stage of development.

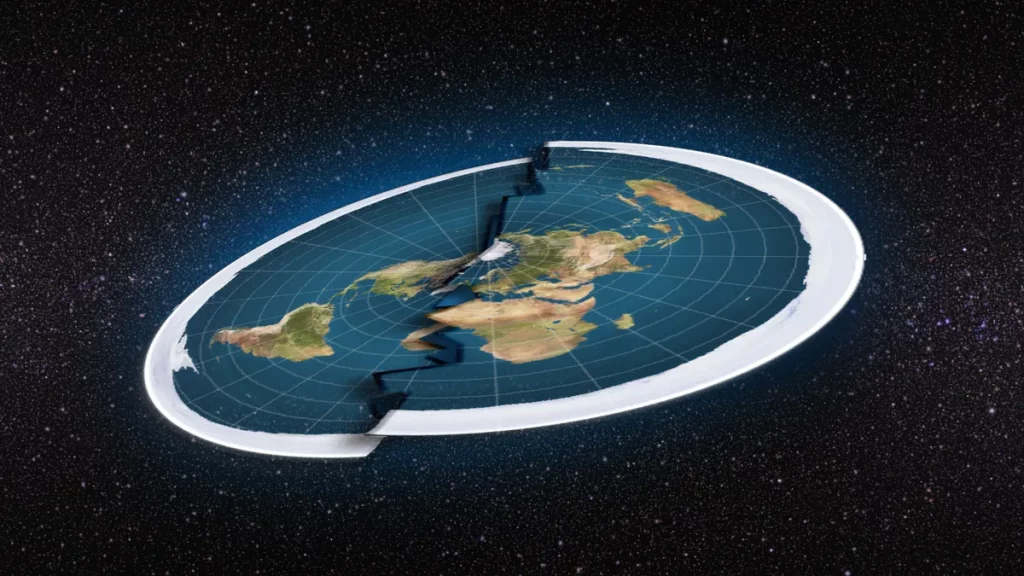

Flat

The most common recurring question right now is one we cannot escape from, and it insists on requiring a proper answer:

Is the Earth flat?

The short answer is that the Earth is not flat, but it is also not simply a circle, nor is it just a perfect sphere. These characterizations are abstractions of our reality, which we call “Earth” in space. The Earth is part of a grand scale “universe,” with the prefix “uni” meaning unification or unity, and the consequent “verse” meaning “many” or multiplicity. The most basic axiomatic definition of the universe is that it is a “unity” of “many,” or a unification of multiplicity. This is similar to the recent quantum term “multiverse.” However, even these definitions of the universe as a continuity or extended unity of scattered, disassociated, discrete measures are themselves abstractions.

For example, when we observe the “heavenly skies,” we see an empty black vacuum filled with discrete points of energy, separated from each other by place and position. Space itself is maintained by the balance of these objects in relation to each other. This picture is the common-sense view of the universe. However, it is not the full conception of what the universe truly is.

The universe has no primary form other than the form that it is potentially any form. The shape of the universe is therefore unstable and always changing. This answer to the former dilemma is still not the full answer to the question of what the form of the universe is. The universe is not stable in the way we observe it, but it is also not always constantly changing into anything and everything. There is a basic hierarchy of principles of logic or a “higher” structure of mathematical principles; the order of these concepts still applies to the form of a “concrete” phenomenon like the universe that contains us. What I mean by the above is the following: our basic principles in any intellectual field, like mathematics, for example, begin with fundamental concepts such as the point, line, circle, etc. From these basic spatial elements, more complex shapes like hexagons, polygons, and so on are developed. These more complex shapes, which actually capture three-dimensional reality more accurately than their fundamental counterparts, are built upon the primaries. In essence, they are nothing more than the relations of these basic principles. At the outset, first and foremost, it is the number 1. The number 1 is the starting point for all other relations. The first basic principle is always one and singular, and then it becomes variable and multiple. This is similar to the idea in all monotheistic religions, where God is always one.

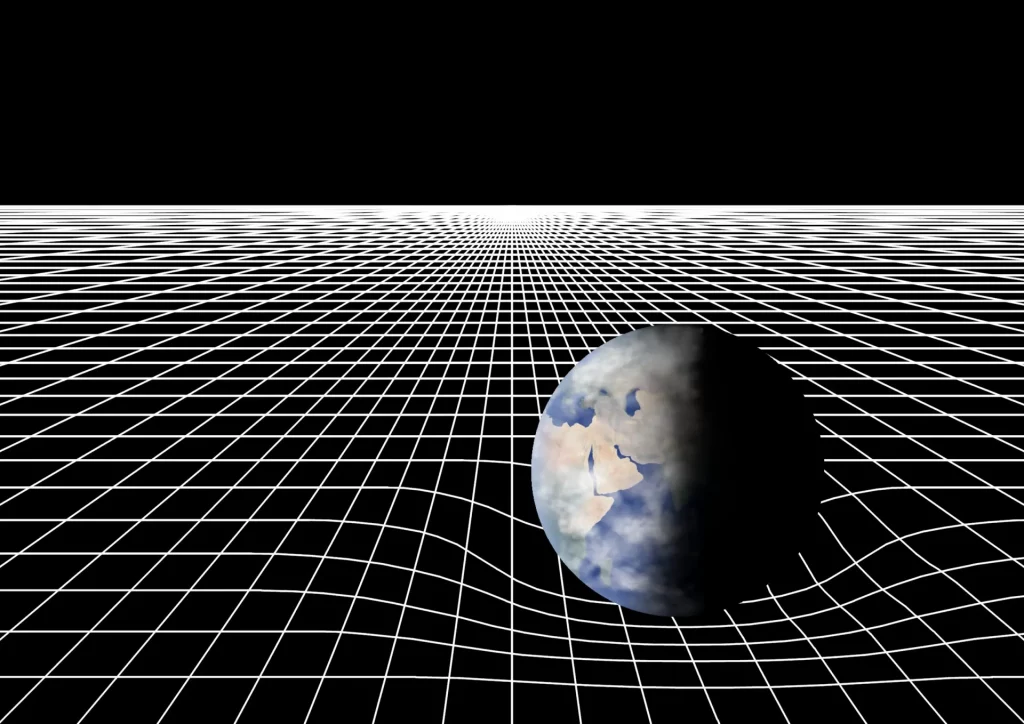

When we say that a complex object like the Earth is “flat,” we are talking about it dimensionally, meaning that at the more primary and fundamental level, it is two-dimensional, or even one-dimensional—essentially, it is just a discernible point of energy. Conversely, if you take any aggregate magnitude in the universe and expand it outward, making it larger by adding more mass, the points forming that area begin to shrink. Eventually, these points combine, forming the same discrete point of energy. From a certain distance, any object or set of objects, which is essentially the same in this case, will appear as a discrete point of energy. If you zoom into that discrete point of energy, it presents itself as variable, consisting of many more discrete points of energy. If you select any one of those points, it becomes variable as well, and the process continues infinitely. The earth is fundamentally flat, but so is spacetime. Three-dimensionally, each object is spherical, but that is a less fundamental dimension of it.

Slab

We must reconcile the common view of the universe—that it is an empty void of discrete points—with the resolution from the “unpredictability of change” in Form as requiring a hierarchical order of principles. This means that we have to look at the universe hierarchically from top to bottom, from general to particular, with the bottom being the most fundamental, and extrapolated outwards into less and less fundamental forms. These forms are expressions of one singular principle. The universe does not have a form, but rather, Form is the universe. In other words, the unity of multiplication means that the universe is merely the order of Forms organized in a hierarchical manner of fundamentals.

It is merely a “slab of nature,” as Alfred North Whitehead used to call terrestrial bodies. A slap is an interesting phenomenon in the universe because it is a figure on a two-dimensional plane. How can you pick out any point on a two-dimensional plane? First, the plane itself is distinguished from the first dimension by the fact that it is a plane, meaning it extends outward beyond itself while maintaining its own identity. Therefore, the point itself is extended outward, while remaining a point, which appears as a line. The first dimension is simply an undifferentiated point, meaning that within that point is an infinite or invariable amount of quantity, such that its content cannot be distinguished. The point contains this condensed energy and is, therefore, a singularity in spacetime.

But the two-dimensional plane discloses that point. The plane is a field where the point exists. A slab is a figure formed by these points, and that figure contains within it content, which consists of more unique forms. So, if you want to explore the universe, you do not go outward, but rather inward. This is not merely a spiritual claim that the universe is found by the soul of man, that to find the universe, you have to find yourself. This is not merely true in a metaphysical sense, as much as the “self” is the singular feature in the universe. The paradox is that “other” selves, outside of its own self-identity, exist. The number of these other forms constitutes a contradiction to the self-identity by being many different versions of itself each subsets in respect to each other. Together, they form a structure, like a solar system or a cell. These structures are organic aggregates, or slabs in nature.

They are also considered “observers” because they operate (move) within this continuum, and they determine form into being, through their internal relations. In other words, they project in their minds objects of their own experience. For example, AI is now generating a simulation of reality and operating within it. This means that the robot scans reality, generates a simulation of that reality in its processor (its mind), and operates within that conception of reality as if it were real reality because it is. The conception of reality actually corresponds to the so-called objective reality it is representing. At the observer level, the reality being generated is simultaneous with the reality from which it is supposedly generated.

The Earth is much more of a deeper phenomenon in the spacetime continuum than just a “planet.” In fact, our entire view of space consisting of spherical bodies of rocks revolving around larger bodies of plasma forming solar systems is wrong! It is wrong because that is not the full picture of the universe, and even if it is partially correct, it is only a very limited, narrowed-down abstraction of the true scale of reality. The number one principle in all of Ancient Greek philosophy up until the modern scientific tradition of German idealism is to never fully trust what you immediately see by perception. The image of the world provided by perception is inherently incomplete, and only through the “light” of “reason” can you penetrate the limited abstraction of the image and reach its fundamental abstract forms. In closing, the Earth is a slab in nature that is penetrable into infinite forms disclosed within itself, and such a structure is the form of the universe at large. Whenever you take any abstraction of the universe, it appears as a slab in spacetime—a set of discrete qualities together forming a singular figure that is picked out by an observer.

Scale

Scale, in the full meaning, is not just “sheer size,” but also the nature of the substance under investigation. In other words, what Forms does substance take, not only the measure of its current scale. When we say that our normal image of space—consisting of planetary solar systems—is an abstraction, we do not only mean that it captures a small portion of the universe, and that the overall universe, in terms of size, is much bigger. This counter-argument almost excuses our theory as correct merely because the alternative is too complex. Understanding the true picture of the universe is not equal to knowing ‘more and more’ of its size. Knowing ‘larger and larger’ areas of the universe is not equated with knowing its true essential nature because, as it seems according to the materialist view, we can have an infinite amount of vast empty spaces in the universe.

Our present theory of space is wrong because it fails to capture the true form of our cosmos. A cosmology that cannot describe the true form of reality—i.e., how it actually looks—fails as a theory. If we closely examine how we describe objects in space, such as planets, we will notice that it conveniently appears to mimic how we observe objects in our daily life. For example, our sense perception observes three-dimensional objects that appear as a certain kind of shape, with each object having edges, curves, etc. We assume that objects in space exhibit the same physical nature as the ordinary objects we observe because our geometric and elementary particle models are presumed to be universal. If we assume that our cosmological models are universal, then the Earth is first and foremost a sphere.

Space alone does not tell us the essential nature of the universe because space itself is just one of many other fundamental properties that form the universe as a substance. As a substance, the universe is a dynamic form, changing in accordance with the observer, who plays a role in determining the substance’s manifestation. It could also be the case that our mind resolves complexity into rudimentary shapes and forms that appear as curved, rounded outlines or circumferences, disclosing content of qualities into the same homogeneous acting identity.

The world is divided into objects, each disclosed by an outline of their shape. However, that outline does not capture the true extent of depth the object discloses within its figure. Infinity may be limited into a finite object by disclosing content in a certain shape; however, the content itself, when disclosed into a finite shape, is not itself finite. It is only made finite by the mind of the observer in order to make sense of it. In and of itself, it remains infinite, and the full extent of its infinity is infinitesimal in depth. The Earth is a singularity; the extent of it observed by us only resolves it into a finite object, round, because that is the most basic and rudimentary of shapes. Its true shape, however, is infinite.

Quantitative

The sphere is more fundamental than the circle or the line because those are 2-dimensional abstractions of it. We assume that the chronological ordering forming a hierarchical process begins with the lowest whole number and transcends upwards into higher numbers, with the latter being less fundamental than the former in the chain of quantitative sequence. For example, Charles Sanders Peirce says that in a sequence, a higher number is always greater than a lower number. For instance, in the series 9998, 9997, …, 98655, 98656, 98657, …, 97988, 97989, etc., 98656 is greater than 97989. Although this seems obvious, what is not evident is that this observation is a “fact” about qualitative objects that are innumerable. A quality is innumerable when an infinity of potential quantities is disclosed by its unique nature.

If we not only apply this principle in a mathematical arithmetic sequence but extend it into the application of quality forming a hierarchical “Pareto principle,” then we notice that the maximum number of effects occurs from the lowest number of quantities. This is the opposite of the sequence of higher arithmetic orders, where the higher the number, the greater the quantity it represents. The concept of “quantitative” is simply defined by this latter feature: as numbers increase in higher order, they represent greater and greater measures of quantities—”more and more” of them. A qualitative measure is inverse, whereby the lower numbers in the order of higher order represent an object more uniquely. For example, the number 1, being the first number after 0, is used to represent a single individual object (i.e., one man is assigned the number 1, or the number 1 is assigned to one car, etc.). As numbers get higher and higher, objects are less precisely represented by them. For instance, 1 man is made up of a billion atoms, but the measure is always less precise.

In the realm of higher-dimensional objects, the lower the dimension (closer to 0 on a series), the more fundamental it is (the more everything else after it depends on it). The reason is simple: the higher the complexity of the dimension, the more fundamental that dimension is. This is logical because a higher dimension discloses more possible sets of variables that may interact. The number 1 can represent a billion different ways because every number is a single number. But 1 billion cannot be 958 million—it can only be that one singular measure.

Spherical

There is an important distinction between physical objects, like the ones outlined in elementary particle physics, and metaphysical objects like the concepts of beauty, truth, love etc., these latter set of objects are not “less” real than the objects we directly observe as physical. Let us distinguish between abstract as opposed to physical; objects.

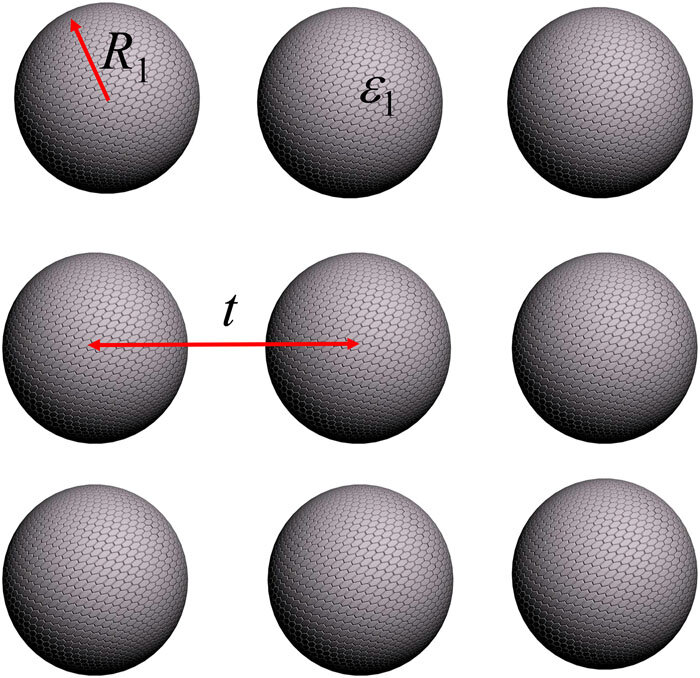

This means two things. First, at the substructure of the Earth, as an object like all other terrestrial objects (both organic and physical), the makeup of such material at the “subatomic level” consists of basic primary abstract principles, such as geometric objects of perfect and absolute symmetry. At the base level of matter, an object like the Earth is made up of perfectly coordinated spheres, or it could be that the Earth itself is a coordinate sphere in congruent relation with other similar forms. In either case, it is either made up of spheres or is itself a sphere that makes up other spheres. In both cases, it exhibits a form of relation that is purely abstract. When it becomes an abstraction, we identify it as finite or particular. It becomes two-dimensional or less-dimensional abstract objects, those same ones of the mind. These abstract objects are not confined to physical form but exist as conceptual representations, existing in the mind as simplified structures that we interpret and identify as finite or particular.

The earth as an elementary particle takes on the form of a sphere. Its circular structure is one abstraction of a sphere as a 2-dimensional object know as a circle. The earth is also a line, and is always flat from a first person point of view, a flat line is a plain. The earth is as much flat as it is a circle, both of which are abstractions of the more fundamental shape of a sphere. When we say abstractions, we are saying a line and a circle are ingredients to make a sphere. The surface itself on a sphere is always a wave-particle duality. Have you ever noticed that if you look at an object that is a sphere, there is always a visible side to it, a “side” of the surface facing the observer; and there is always a side of the object that is hidden behind the visible face of the surface away from the observer.

Solid

The next question is, why is a sphere the most fundamental shape of the earth? The answer is not because the earth is ONLY spherical. The earth is not only a sphere. This answer becomes clearer if we actually understand what the nature of a sphere truly is. The definition of a sphere is loosely defined as; a sphere is a surface, presumed to be solid, with every point on its surface equidistant from its centre. The latter part of the definition contradicts the former. A sphere cannot entirely be solid if all of its points are equidistant from its centre.

The reason is because the centre of a sphere is ultimately any point on the circumference of a sphere. This does not mean that the point is ‘on’ any arbitrary part on the surface. The surface itself is the consequence of all the points being equally away from each other because they maintain the figure of a point extending it away from each other, then it is as if its 2 dimensional self is being stretched outwards in every direction such that the figure and the surface each become the other. The figure is the point, and it becomes the surface. This is our representation for a 3 dimensional model, it is fundamentally flat, but abstracted into the mind as solid, it has depth in which the mind of the observer can fall into.

(See the nature of a sphere section)

Singularity

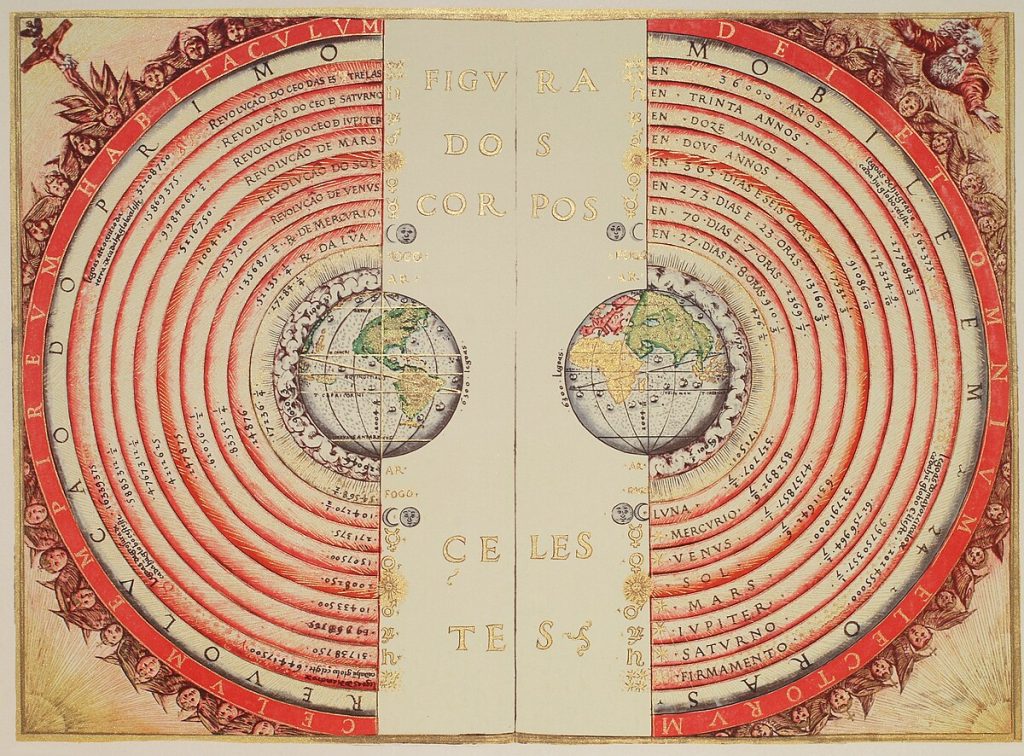

In ancient traditions, the Earth is often depicted as two spheres: one sphere showing the front side facing the observer, and the other sphere showing what is supposed to be the back side now as the front – back and front. However, this model is incomplete because it cannot represent the singularity within the sphere.

The singularity of a sphere is demonstrated by a point, but the geometric function of a point does the opposite of what the definition of a singularity entails. A singularity is an infinitely inwardly extended point in space and time. The side at the back of the sphere, which is invisible, extends into an infinitesimally extended duration. We often confuse infinitesimal with being infinitely small, but the magnitude of the duration is only relative to the scale of the position from where the observer is in relation to the point. The Earth is a point on the fabric of spacetime, an infinitesimally internally extended magnitude. What we see as the Earth, consisting of continents and bodies of water, is only the finite tip of a singularity’s surface. The Earth is not merely a sphere; behind that sphere is an infinitely extended duration of all possible moments and events in spacetime. We exist only on a small crust off the infinite wormhole of reality.

While on the same note, the Earth being infinitesimally extended does not spatially make sense because something internally infinite is limited by the self within which it is infinitely extended. From a two-dimensional point of view, a three-dimensional observer perceiving the infinitesimal would appear to see it as a two-dimensional object. In this perspective, the object would just look like a circular slab in nature, changing scenes — the appearance of rotation.

However, rotation is presumed to make the same finite rotation, from the back to the front. In reality, we don’t actually see the full extent of the rotation. We only perceive one side at a time, with the concealed side taking the place of the visible one, then expressing from the hidden side to occupy the front portion. We assume this is rotation because the two points are in a pendulum-like motion, changing positions one behind the other.

But if the point is a singularity, then its change of position would each time take a unique form for the observer, even if they do not notice it. There is always something new that emerges within a singularity.

‘Being is becoming, becoming is non-being, non-being is nothing, and nothing is being.’

Problem of Structure

The problem of establishing a “beginning” relates to the issue of trying to produce structure in a work of metaphysics. The challenge of structuring a body of ontological work is difficult because it involves attempting to talk about “everything” while maintaining a specific order of topics for the reader to follow. Hegel says:

“As the whole science, and only the whole, can exhibit what ‘the Idea or system of reason’ is, it is impossible to give in a preliminary way a general impression of a philosophy. Nor can a division of philosophy into its parts be intelligible, except in connection with the system. A preliminary division, like the limited conception from which it comes, can only be an anticipation.”

All scholastic pedagogy assumes that there is a specific order in which subjects must be taught. It is proposed that we begin with the most abstract of subjects, like mathematics, and then move on to the more concrete subjects, such as the social sciences. In school, we learn mathematics and sciences in the morning, and then all the social studies in the afternoon. For example, this is the difference between exoteric and esoteric studies. This structure is valid on some level because the abstract is more general and universal, which can then be made applicable to the more specialized and particular concrete cases. This structure is derived from an idealist ontology because it contrasts with the crude, intuitive way of understanding knowledge.

Naturally, the most applied forms of study, like communication, construction, cooking, etc., are what we think humans first learn. The more abstract subjects, like philosophy and mathematics, are learned last—by “last,” I mean after taking care of these applied necessities. In more developed societies, once these basic necessities are taken care of, the more abstract courses become the first and most immediate forms of learning. However, even in primitive cultures, the most abstract subject of all—religion—is still taught first and foremost and governs all forms of applied conduct. All ethical and moral conduct is driven by religious inspiration, while art and architecture are governed by mathematical insights.

Conception – “design”

Conception translates as “design” in French.

There is no precise word to describe the active aspect of determining an event, but there are many words that describe a reactive response to some external stimulus. Words like “instinct” and “intuition” define the sense where the knowledge of an event is derived “reactively” from the occurrence of something outside the control of the observer’s “will.”

More specifically, instincts—and less so intuitions—are survival characteristics that respond to stimulus. Stimulus can be objects or other life forms, but the events in time themselves are also stimuli. The way the mind reacts to an “event” is much different than the way it reacts to an “object.” When the mind reacts to objects as stimuli, it invokes some kind of response; however, for an event, the organism reacts with a response to an unknown action.

A “response” is an active form of conception rather than a reactive behavior. The word “conception” in French means “design.” From this meaning, conception has more of an active element, rather than a reactive one, in English. A conception is the design of an event. The way this works in time is very different from how time is experienced during the present moment. During the present, the organism must maintain itself and thus is reactive to any immediate stimulus that directly affects it, which is why we have the notion of “conception” as a reactive form of knowledge to an external stimulus, such as perception.

From a standpoint of time beyond the present, the mind conceives certain possible events and envisions details it can pick out by observation. We commonly confuse perception, which is the act of seeing with the human eye, with the concept of conception, which is the act of being conscious through the mind. The mind undergoes a “search” mechanism through the possibilities of potential events and determines details in a certain way. In this way, it determines the present in a future moment. The present, at some point in the past, was designed by a future conception. In other words, during the present, the conception determines a set of possible events.

(38 Aristotle tr. Jowett rev. Barnes, Metaphysics IV.1.1003a1.25-30

Aristotle tr. W. D. Ross, Metaphysics IV. Part 1)

Done-for-its-own-sake

Having a formal structure cannot be a proper aim for ontology because the sciences must be pursued entirely for their own sake and for no other purpose, including the purpose of having some kind of structure. A structure happens naturally from, and as a result of, habitually engaging in philosophical writing and thinking over a long period of time. The sacrifice of philosophy is “time,” which is why it is not ideal for acquiring immediate fame or money. However, the philosopher must already have the right “means” and resources to ensure they have the “free time” to philosophize. By “free time,” we do not mean the residual time after a long day of work, but rather that philosophy must be incorporated into the work process itself, no matter what that work is. For example, if you’re building a house, philosophy must somehow be engaged in that process. The result will turn out better, after all.

Doing something for its own sake is the way the mind derives the idea in itself. The reason for the action is identical with what that “thing” is. Hegel says:

“Here, however, it is premised that the Idea turns out to be the thought which is completely identical with itself, and not identical simply in the abstract, but also in its action of setting itself over against itself, so as to gain a being of its own, and yet of being in full possession of itself while it is in this other.”

When the mind thinks and tries to derive a certain idea, there is the intent of obtaining that idea. If the reason for thinking is simply to think for its own sake, that is identical to getting the idea as itself, as what it is. However, if the reason for thinking is for some other purpose, like teaching or fame, then that intention becomes the idea itself, and any other idea the thinker thought they could use to get to the real reason they are after simply gets lost. So, if the reason for doing philosophy is to gain fame, then fame becomes the idea I am after, and philosophy, which is supposed to be used to get to fame, becomes the secondary means. However, philosophy cannot be a secondary means to an end because it does not directly result in anything other than the truth. Since getting fame does not necessarily involve philosophy, it may involve a complete contradiction to philosophy—perhaps buffoonery is the best way to become famous. Therefore, philosophy—or anything else not done for its own sake—is not itself and can becomes anything else but itself.

Philosophy cannot depend on the idea of trying to formulate some structure because that aim changes its philosophizing to be tailored to the limitations of the structure it has set upon itself. Thus, it becomes compromised by that structure, even if the structure is true. Philosophy is interested in the capacity that allows things to be structured, not just in how they are structured. On the other hand, philosophy involves science when it looks upon a certain structure to get to the bottom of the capacity that gave rise to that structure.

Fundmental Science(s)

The specialized domains of science, such as physics, chemistry, biology, etc., assume an order where one is prior to the other, in the sense that one informs the other but does so in a more fundamental way. The substance each science deals with determines the level at which it is fundamental. For example, we learn physics before biology in school, and biologists take preliminary courses in chemistry, i.e., biochemistry. However, these sciences are fundamental not in the sense that their subject matter constitutes the source of causation for the other. We do not necessarily say that the facts of physics cause the organisms of biology, because the inverse is also true: organisms produce movements that are fundamental in physics. The idea that all the sciences pertain to the same Being is first in the logical sequence of knowledge before the sciences can be taken as particular divisions of a specific field.

The question of “what they are divisions of?” on the one hand, cannot be fully discovered during the duration of the science because a science must presuppose a nature to be essentially true before it fully apprehends it. On the other hand, the subject matter develops through discovery and changes while remaining fundamentally what it is as the same field of study. Even logic, which discovers its subject matters throughout its duration, is a specialized science in the sense that it assumes the substance of thought to be primarily a true nature. The question of a special science is not whether the topic is true or not, or what the topic is; but in what sense the topic is true? For example, in what sense is biology a true aspect of Being? The sciences talk about certain kinds of objects, all of which are certain kinds of being(s), or being in a certain way. For example, the study of biology, in an ontological sense, simply means that Being has an aspect of itself that is living.

Concept

When science talks about the concept it “takes” to be fundamental for its investigation, the concept is never really what it is, or rather, it is nothing that can be “known.” A concept has no identity, yet it identifies knowledge for us. In other words, the identification of a concept may be arbitrary, like the sound of words or the language of numbers, but what it identifies is not arbitrary, such as the nature of a certain object. A concept is generally known as an abstract notion, which defines it partially as speculation in the right place, or roughly about the right thing, without pinning down what the right thing is—only that the idea is on the right track toward gaining its desired aim.

This leads into a second definition of ‘concept’ as a plan or intention, in the sense that having the concept of something means having its understanding and demonstration. For example, when you read a blueprint, you see all the paths, ways, and the overall structure and capacity of the thing. This definition is completed with the more Classical Latin definition of “concept” as conceptum, which means ‘something conceived,’ from Latin concept- ‘conceived,’ concipere, com- ‘together’ + capere ‘to take.’ This final definition explains the ‘concept of a concept’: rather, a concept is simply the reference to the capacity in which a certain reality is disclosed at a certain level and in a certain way by grouping together a class of components and combining all their aspects. On some level, the conception takes itself and the capacity into a set of capacities that it then takes as the objects conceived by it.

Science(s) presuppose each other

Whitehead explains that specialized sciences always presuppose knowledge from one another. He says:

“Every special science has to assume results from other sciences. For example, biology presupposes physics. It will usually be the case that these loans from one specialization to another really belong to the state of science thirty or forty years earlier. The presuppositions of physics of my boyhood are today powerful influences in the mentality of physiologists.” (Nature Lifeless 178-179)

To what degree does a scientist maintain fidelity to one specialized science while partaking in another suggests that no thinker, “properly” speaking, is a pure specialist in one field; rather, they contribute to and partake in a specialized body of knowledge. Fields of study can be specializations of Being, but no single being can be a speculation of science because science deal with nature(s). A true specialist applies the specialized facts in a generally true way. Being is every science combined to form a total picture of reality. However, these very sciences, from which you pull the truth to create a general picture, are each part of a body of knowledge that has no general picture of reality.

The issue of what it means for a science to be fundamental is an ontological question, not a technical one. The specialized sciences derive abstractions demonstrating the fundamental nature of a phenomenon, but as Hegel says, regarding this:

“[…] How much of the particular parts is requisite to constitute a particular branch of knowledge is so far indeterminate, that the part, if it is to be something true, must be not an isolated member merely, but itself an organic whole. The entire field of philosophy therefore, really forms a single science; but it may also be viewed as a total, composed of several particular sciences.” (Encyclopedia of the Philosophical Sciences 16)

Any “given” object, at a “given” moment, involves all the sciences simultaneously because it involves facts from each one of them. However, every fact from a science must be taken as an objective illustration of the whole. For example, when we talk about something specific as a “cell,” we do not say it is limited to a particular animal only, but belongs as the basic unit of life for all animals. Yet, there are so many different kinds of cells that compile together to form the many diverse types of animal life forms.

Specialized Science(s)

These general domains of science that we call “biology,” “chemistry,” “physics,” etc., can only provide a general picture of reality by describing and bringing together the general laws of nature into a specific moment (instance). The basic rule of physics, said in the most general way, is that the most fundamental of the specialized sciences describe certain kinds of interactions happening between certain components; all of these interactions always relate under certain dimensional measures.

In terms of the difference in dimensional magnitude, the “chemical” components operate at a more microscopic level than their “biological” counterparts. Yet, the operations of physics operate at much more macroscopic scales than the chemicals, and the chemical operates at a more macroscopic scale than the biological, with the biological being more microscopic than the two former. Planets, which are ultimately macroscopic aggregate compositions of fundamental chemicals, are held together by a formal shape that is in motion, or is rather “thrown” around by the physical laws of physics, which are indefinitely interacting with one another. For example,

“Newtonian laws: Law of Universal Gravitation: Every particle in the universe attracts every other particle with a force that depends on their masses and the distance between them. First Law (Inertia): Objects in motion stay in motion, and objects at rest stay at rest, unless acted upon by an external force. Second Law: Force equals mass times acceleration (F = ma). Third Law: For every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction. Law of Universal Gravitation: Every particle in the universe attracts every other particle with a force that depends on their masses and the distance between them.”

These laws describe how the directions of motion, which we call forces, interact in certain ways to constitute what we observe as physical solid objects. The world appears to be in motion for the observer because every other object is already in inertia. This means that each object itself is inertia — it is solid, or its components are in such harmony with one another that they form an indistinguishable, unified form. While the motion described by Newtonian physics occurs between objects at a certain dimension, where the observer can discern the difference in space between them, each object forms an identity. In other words, each object moves away from or in relation to others at different distances, and they possess a size that makes them comparatively distinct in mass. From this dimension, the observer can just barely see the spaces between objects, enough to differentiate them by their motion in space. However, at different dimensions, such as the microscopic level, the distinction between objects becomes so small that the space between them cannot be distinguished. As a result, there is no discernible space, and they form the same interconnected being.

Biology, Chemistry, Physics

Biology, chemistry, physics etc., are conceptions of reality at certain fundamental domains, and as such, they are abstractions of reality. However, this comes with limited assumptions. For example, physics, chemistry and biology are mainly studied at microscopic scales—such as subatomic, molecular, and cellular levels—due to the fact that science is currently equipped to conceive of and study such phenomena. It is more accessible to consider biology as the study of the cellular structures of life forms rather than viewing it at macroscopic scales. For instance, we do not identify the planet Earth as a biological organism, even though it is abundant with all the living forms that biology concerns itself with.

Cosmology, which is “the scientific study of the large-scale properties of the universe as a whole,” looks at the universe’s large-scale properties, but these are not attributed to biology or chemistry in the same way they are at smaller scales. Partly because they do not exhibit the same characteristics—planets do not have the same kind of “cells” as mammals do—there is a clear distinction. However, we can say that as we expand outward, the same properties of biology remain fixed and true. For example, while a planet may not have the same “cells” as a mammal, a mammal within it can (philosophically) be compared to the cell of a planet.

The complexity might be the same: there are microbes that roam around the human body, just as mammals roam around the Earth. Yet, the body of a human is identified as a conscious being whose actions are recordable because they operate at a certain speed of time, where they can be classified and seen as a sequence that has the same duration. The rationality exhibited by the Earth, however, operates under a different timeframe. Thus, what a human does in one minute, the Earth experiences in a relative time scale that may correspond to thousands of years.

From a limited conception of time, an individual derives observations about the universe using very limited abstractions. However, the individual can derive a more complete picture by combining all the snippets of truth discovered by historical predecessors with their own immediate experiences. This creates a concept of reality, which is a general abstract notion, as it involves piecing together different conceptions made at various points in time, and it extends over durations that surpass any particular conception of it.

The limit of science – the moment when a cell becomes a molecule

Facts derived from the specialized sciences become ontological when they reach a limit of knowledge due to their specialization. It is at this limit that one science extends into the territory of another. At this point, the sciences belong to a more fundamental union known as their ontology. The moment when a cell stops being a cell and becomes a molecule, and when molecules start becoming atoms, is a distinction between the sciences that is not clearly defined. We can say that, ultimately, a cell is just another way of being an atom, and an atom is another way of being a molecule. Each form is equally fundamental as the same being.

A fact is simply a deception of a fundamental abstraction about the universe. The association of a fact with an “abstraction” can be confusing, as it implies that a moment occurs and then passes away. But how can something that passes away during a moment constitute a fundamental principle or law of the universe? Laws of nature are meant to be universal, constant, and eternal. However, the eternity of a principle is not determined by whether it is passing or consistent merely; rather, it is a matter of degree in time. For example, the moments most immediate to an observer come and go in a matter of seconds, minutes, or hours. However, if you extrapolate this temporal degree to a macroscopic scale, certain planets, stars, and terrestrial bodies have been in existence for billions of years. Some substances, like chemicals and atoms, are eternal because their presence constitutes the same necessity for the universe to remain as it is.

An atom, for instance, is an abstraction of the universe. While it is still a fundamental moment—one as old as the universe itself—it remains a moment in time. A fact depicts a fundamental abstraction about Being. But how fundamental a fact is depends on how abstract that abstraction is. A concrete object serves as a medium, transferring one abstract principle to another, much like a neural synapses transferring information. However, the difference is that the information is not transferred from one receptor to another; rather, it is used to form the fibers that structure the object into a form.

In the same way that the canals of Earth serve as passageways for water to flow through, with one element (earth) being denser than the other element (water), matter itself is more dense in extent than an abstract substance like thought. Therefore, thoughts, being the least dense substance, possess the fundamental forms through which objects are conceived by an observer. These forms actually make up the conception of the object. In this sense, the observer acts as the medium of the transaction between matter and thought, concrete and abstract. The difficulty arises when science is specialized to a particular nature of phenomena. This particular nature, in turn, begins to take on a nature of its own.

To structure a hierarchy of the sciences based on how fundamental the abstractions they depict are, we must start with the nature of Being as the source of knowledge, which is the starting point for ontology. The standard for measuring how fundamental a science is relates to the degree to which the abstraction the content of the science deals with is fundamental. The closer the content approaches the abstract nature of Being, the more fundamental the science ‘is’ in relation to other sciences. This is why mathematics, for instance, is considered the most fundamental of the specialized sciences, while ontology is even more fundamental, as it is the most foundational study of the philosophical sciences. Ontology explores the Being of the most abstract facts, while materialistic sciences explore how these abstract fundamental facts describe Being.

“Being” is the first subject-matter

When Aristotle says that “Metaphysics investigates not a specific part of Being”, but Being in-and-of-itself, he is addressing the difficulty of grasping the “first causes” in a field where all the principles of the specialized sciences coexist simultaneously. Being reveals itself as an immediacy across all the sciences and is fundamental in all particular fields. In other words, every particular subject is a “Being” for study. Physical science sees the universe as a world of objects, while metaphysics views the universe as a world of “Being(s).” The same physical objects, when viewed from different perspectives, are seen as Being(s).

This does not mean that we can call anything “a Being.” For example, inanimate objects exist, but they are not considered a Being in the sense that they are not alive. Life is a requirement to be a Being, but life, as it defines a kind of existence, involves active self-agency. This self-agency allows a Being to determine a set of objects in a specific way in order to operate a certain function. The word “organism” is defined as “a whole with interdependent parts, operating in accordance with a function.” In other words, an organism is an integrated body, whose whole form is made up of parts working together to fulfill a function. The aim of this function is always first abstract and then concretely executed. For example, stomach acid, on its own, is a corrosive chemical, but the body figured out how to use it as an important aid in metabolism.

The body evolved to synthesize chemicals for the breakdown aspect of metabolism. The stomach is protected from acid by a layer of mucus and bicarbonate. Acid is denser than the mucous membrane, much like how acid would sink to the bottom if poured into water. The acid sinks to the center of the mucous membrane that encapsulates the stomach lining. This allows, when food is dropped into the stomach, the acid to help break down the food, and the proteins are absorbed by the stomach. The organism has an innate knowledge of chemistry and fulfills its abstract aim, which is a hypothesis, by combining parts in the environment to form a single whole that operates on a function toward fulfilling that aim. The aspect of this process that involves the self-agency of determination is life. A Being is the whole complex of this living process—the organism as a body living, acting, and carrying out its aims.

All the sciences have the concept of Being as their subject matter. However, Being comes in many forms. A science becomes a specialization when it concerns how Being presents itself. Metaphysics, Aristotle says, investigates not a specific part of Being but Being in-and-of-itself. This means that Being converges all the sciences into a discussion about the same phenomenon. Being is not the general category that simply groups particular phenomena together, since that alone does not tell us why something exists in the way that it does. In other words, just because a thing exists does not explain why it exists in the specific way that it does; rather, Being is universal by becoming the particular in each particular thing.

Ordinarily, the object that appears to be a specific thing is confused with the particular, which partakes in a general category known as Being because it is just one specific thing among other specific things, all of which share the commonality of Being. Yet, this does not explain what Being is, because it reduces existence to the diverse complexity of different objects. As a result, the category of Being becomes a broad classification where completely different things are grouped together. A fish and a Spirochete bacterium are not the same kind of Beings, yet under the general category of Being, they are treated as equivalent. The concept of Being must distinguish these differences in life forms from one another and explain why they are different. This is the feature that made Aristotle the pinnacle of the Ancient Greek tradition: he made Being the thing that actually explains why something is particular.

Ancient Greeks on Being

Being defines what it means for a ‘thing’ to be particular because the any ‘thing’ is partaking in this fact we know as Being. If we can figure out what this fact is, we can understand what all things, no matter how peculiar and different they are from each other, are trying to do. If we replace the category of Being with Substance, as Aristotle does, it becomes clearer that each peculiar thing is trying to actualize some essence, or rather some essential aspect—again, not yet defined by what that essence might be, since the essence is not some independent goal external to the thing, but is identical with what the thing is. We call this the preservation of the self, but more accurately, it is the self-actualization of the thing, or simply the duration that constitutes the lifetime of the thing.

If we replace substance with Reason, as Aristotle does, but more notably Hegel, who defines ‘substance’ in terms of Reason, then we get closer to the mark. All specific things become expressions of Reason, or they are moving toward becoming rational, as this is what they are potentially. Reason is their ideal; things develop Reason, or the essential capacity that makes them what they are, and they use Reason to be an expression of it.

Greek philosophers before Aristotle are preoccupied with the question: What is Being? Being was considered too general of a concept, alienated from the particular forms it took. The pre-Socratics began by asserting the idea that there is an ultimate Being, and then they moved on to place a particular object in that ultimate position as the cause of all things. The truth of this approach lies in the association of the universal with the particular, rather than the idea that one particular principle can take the universal position, of ruling over all other particular things. Substance is not vague because it presupposes a nature with particular characteristics that are conceivable.

Business of Science

Principles of the Good- truth, love and beauty!

The science of ontology concerns the study of the ultimate nature of reality, which is defined by three domains of knowledge: the intellectual, the ethical, and the aesthetical. These are further elaborated as “love, truth, and beauty.” These principles represent the “Good” or ideas about what it means to be ”Good”—not only in terms of being a good person, but also in terms of what it means for anything to be good. These values of science are also “ideals” of nature, meaning they are the reasons for nature to exist and constitute the aim that nature works toward actualizing.

“The business of science is simply to bring the specific work of reason, which is in the thing, to consciousness” (Hegel, Philosophy of Right, p. 48). In other words, science constitutes an essential part of the developmental process toward acquiring self-consciousness, which, as the “end” of nature, is simultaneously its initial aim. Aristotle defines “substance” as the move from potentiality to actuality. The path of evolution is to actualize the potentials of nature, and the process of doing so is informed by a sense of indeterminacy.

The business of science in today’s terms is relevant because it experiments on the population with certain advancements in technology. The conflict of interest in this task arises between the natural development of technology through the development of human reason, while simultaneously that technology is being experimented on by the very observer who brings it into being. The latter case raises questions about ethics, or more specifically, morality. However, morality seems to be an ideal through which the process reveals the truth. The business of science in its true sense is to synthesize the universal conceptions of man with man himself as a finite being. But in doing so, the process of morality is revealed because the subject undergoing the process is man himself, as he is both the generator and the user of his own productions.

The end determines the means within the rigidity of the law

Whenever there is uncertainty, the idea is that the “end determines the means with the rigidity of a law” (Winslow, Historical Materialism, 2007). This means that, in the study of entropy, the antidote to chaos is the general rule that the end determines the means. This is counterintuitive because we typically think that labor is required first to produce the result. However, labor itself is initiated and governed by the plan—the abstract blueprint. This is not a form of predetermination in which the already laid-out plan is simply executed; rather, the content is never merely given in nature. Instead, its realization is the act of conceiving it into being. The end is not where a process finishes or results, but rather constitutes the aim that initiates the beginning. The ‘real’ is distinguished from the ideal on the basis that one is the “end,” while the other involves the developmental process toward realizing that intent, which, in itself, has already determined the means for accomplishing it.

This means that the initial conditions of Nature begin from the most limited and alien circumstances, the furthest away from an ideal state. The process of universal history advances towards acquiring capabilities that come closer to realizing these ideals as real aspects of life. Marx makes the following claim to propose the ontological idea that “Reason governs the world”, and always has, since the beginning: “Reason has always existed, but not always in a rational form” (Letters from Marx to Arnold Ruge).

Empirical analysis shows a more “crude” state of nature where the relations between ”things” appear to be the opposite of what is known as loving relations, and opposite to what is defined as ‘rational‘. For example, the universe, at first glance, appears chaotic, random, and happening without an end or aim. Even more specific observations that do reveal some semblance of rational life and order exhibit relations between each other that are non-ethical by our standards of love and care. All animals violently eat each other, and even at the human level, people are not necessarily beautiful beings, nor do they always express truth and love. For example, throughout human history, the only recorded fact is that a group of powerful minorities enslaved the majority, or killed them in war. The majority of people can seem selfish, deceitful, and aggressive. So it is easy to derive from this observation an ontology that denies any truth, love, and beauty in the world, seeing them as constructs of “ideals” that are never realized in reality.

However, the true constructs are the abstractions derived from what is immediately presented to the observer as the condition of the world, which is then taken to define the ultimate aim of the nature. The cynical ontology sees the world as meaningless, crude, and bad. But even if we begin from this premise, we still have to ask: What does the world in this picture aim for? We cannot say it aims for badness or the continuation of itself as bad because it has already achieved that, assuming we start from the present. Therefore, the universe would have no aim. But if it has no aim, then it aims for nothing. Yet, nothing would then be a better condition than the bad condition the world is already in, and nothing cannot be an ultimate aim. If the universe, assuming it has an eternal timeframe, had already attained nothing, there would be no things at all, which contradicts the fact that there are things capable of being apprehended by Being.

Thus, the Good must be an end for the situation of the world beginning as bad. Or rather, the Good is simply the capacity for the ‘bad’ to be at least better. The Good, as an aim for the world, defines what it means for the world to be a developmental process. But the Good is an ideal, and the entire field of evolution exhibits relations where, essentially, every animal eats and is eaten by other animals. These relations are development toward relations of love, even at this crude level. The construct, in fact, is seeing these ”crude” conditions in the world as the final and ultimate point of the universe. This is only taken as bad if we take it personally—in other words, from the standpoint of self-preservation. From such a perspective, these relations are not good. But these primal relations ultimately continue life as a species, and the general trend of species development is toward better and better rational capacities. Whether from a smarter physiology to a smarter psychology, the system organism is becoming smarter in digestion, vascularity, immunity, etc., and psychically in terms of neurological, perceptual, and all other forms of sensibility. We can argue that dogs have a better sense of smell than humans, but it is the overall operation of the psychological operations along with the physiological that contributes to a higher sense of self-consciousness, which is the measure for determining the complexity of a life system.

Is war bad?

We say that war is bad, and it certainly is by no means good. But those who argue that war is bad in the sense of being a “misfortune” and something the world should do without do not understand what it means for history to be a developmental process. War is present at the earliest evidence of any human group formation, whether tribal, cultural, or contextual. If war is bad in the sense that humans could do without it, why has it remained the oldest form of relation, and why is it not abolished? The reason is that war remains a fundamental way to resolve issues and is necessary for development. War is the only way man can learn in the crudest sense. At the end of every war, we see a great breakthrough in the development of world history. Particularly in the biggest of all wars, WWII, the world was at a potential end, but ended up in a complete renewal. As Hegel says, “World history is a court of judgment” and a “slighter bench of ideas” where man is reproduced only for the sake of sacrifice. The ideas of man are not merely theoretical, they are implemented throughout his relations and are reflected throughout history.

These are not divisions per se, but rather the fundamental bedrocks of science, with each concept presupposing the others for a complete discussion of itself. The intellectual part of ontology concerns what it means for a thing to be ‘true’ and what it means for there to be an ultimate truth, of which the specialized sciences are a particular demonstration. In philosophy, the study of Truth is not fundamentally epistemological, but metaphysical, dealing with the concept of Being as essentially a substance. The exposition of this inquiry has found success in the idea of idealism—that thought, or rather in modern terms, “Reason,” governs the world (history 25). The substance of the world is Reason, or nature exhibits rationality (order). But what this ultimately means has an ethical basis: Hegel says, what is rational is defined by what is ethical, or what is good. There is no real distinction between what is “Good: and what is reasonable, because what it means to be reasonable is what it means to be good, and vice versa. The entire Ancient Greek tradition held this notion as their principle. The intellectual domain of ontology concerns studies on truth, talking about the ultimate substance of the universe and its specialized demonstration in nature. The ethical domain discusses the behavior of this.

‘Education is the “art of making man ethical”

In ontology, the truth value is inseparable from the ethical. In other words, being intelligent is identical to being ethical. This does not concern the shallow sense of morality, which refers to customary conduct and social behaviour—what we often take as the basis of morality. We might say, “Why can’t everybody be nice?” or “Why is there no world peace?” These cliché generalizations about what constitutes the “Good” are naïve abstractions derived from a complex system of ethics, used to simplify and define it in a way that individuals can “feel” they have knowledge of the good. However, in all studies of the Good, vices are preconditioned forces that the individual must overcome, and virtue is the direct effort of transforming these bad behaviours into positive habits.

There is a universal ethics in the world. This is the behavior of matter we call universal and rational. It also encompasses all forms of mutual and reciprocal relations. For example, when one wolf yields to another, lion chasing a gazelle, and attraction and repulsion—these are the ethics of nature. We explain the behaviours of nature as laws, but they are really behaviours of Being that have expanded over long periods of time and have established themselves as law. Hegel says: “Education is the art of making man ethical.” This is where the ethical and intellectual components of ontology form an indivisible bond.

A good existence requires the full development of one’s virtues, of which there are two forms: (1) moral virtue and (2) intellectual virtue. Truth requires developed capabilities, both for its actualization and recognition. These developed capabilities include rational and ethical aspects, or what Aristotle outlines as virtues, of which there are two types: moral and intellectual virtues. For instance, a “universally developed individual” possesses both phronesis (practical knowledge) and episteme (theoretical knowledge). For example, he produces the piano than plays beautiful music on it; he has the plan and the capability to execute that plan bringing it to fruition. This individual uses virtues when partaking in “justice,” which, according to Aristotle, is the practice of “complete virtue […] in relation to our neighbor” (Nicomachean Ethics, Book V). Justice is complete because it is not just the practice of virtue to one’s own self, but also extends the application of virtue in relation to others.

According to Aristotle, “justice” is the ultimate virtue because it requires and encompasses all virtues for its actualization. These developed capabilities—e.g., “an eye for beauty of form”—as well as the experience of such beauty, are the true “currency” exchanged in the “relation of mutual recognition.” Producing in “the true realm of freedom” is an exercise of praxis, i.e., activity for its own sake. “Free time,” in such an activity, “is wealth itself” (Winslow Marx, 1971, p. 257). More time is made for the enjoyment of “free activities” in “the true realm of freedom,” such as spending more time playing beautiful music rather than making the instruments required for such music. “The realm of necessity,” i.e., instrumental activity or poiesis, is consistent with “the true realm of freedom” insofar as they both express the “universal.” Producing in “the realm of necessity” is “universal” because it also requires developed ethical and rational capabilities to create the necessary means for the end. For example, in order to play the best piano music, one requires the best piano.

Every science is an idealism

The loose term “metaphysics” is the science of “ontology,” which concerns ideas about the ultimate nature of reality. In this inquiry, the terms “metaphysics” and “ontology” will be used interchangeably to define the study of Reason, which alludes to the principle of Nature wherein abstract notions constitute fundamental physical changes, both are models of each other. Reason is the abstract; nature is the concrete. Both are different aspects of the same fundamental topic of Being. The extent to which their connection is carried out determines the success of the inquiry.