Misappropriation of Metaphysics

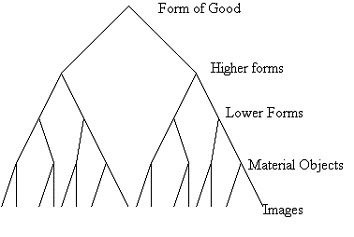

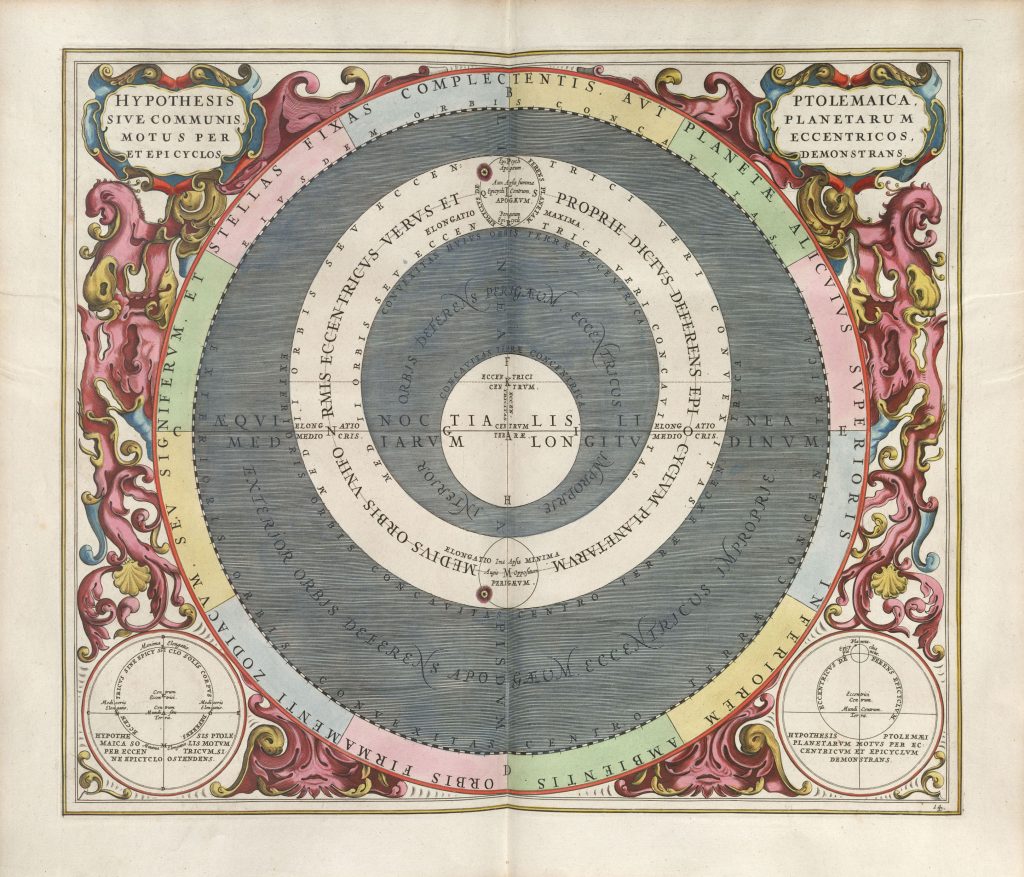

Our modern science today fancies itself complex because it is technically nuanced. It involves many connections between axioms and a diversity of facts, yet all of this is essentially an exercise in redundancy, reiterating the general truths that have already been communicated by ancient philosophy. The limit of any unique modern scientific fact is the universal truth it expresses, which has already been established.

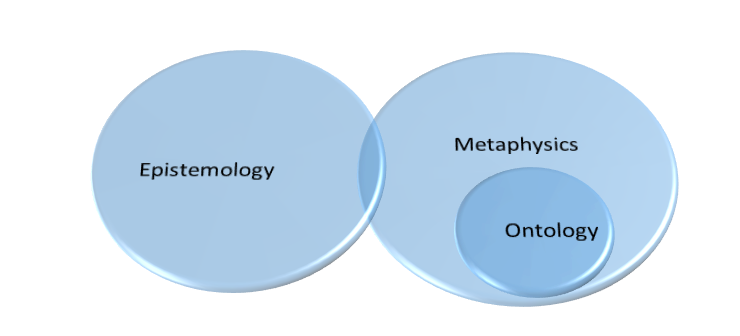

Referring to metaphysics merely because something is unknown or too difficult to understand is a misapprehension of its purpose. Metaphysics is not just a term used to denote unattainable knowledge; its principles require justification, just like every other scientific discipline. In fact, during the time of Plato and Aristotle, the term ‘metaphysics’ was not even used. Instead, it was called the ‘inquiry into the study of Being,’ which is understood today as ontology.

Metaphysics has never carried the same meaning since the time of the ancient Greeks. We mock the ancient traditions for having metaphysics without physical science, but in reality, they were the same thing. Today, however, we have separated them, claiming one to be the successor of the other.

Quantum reared to the older metaphysics

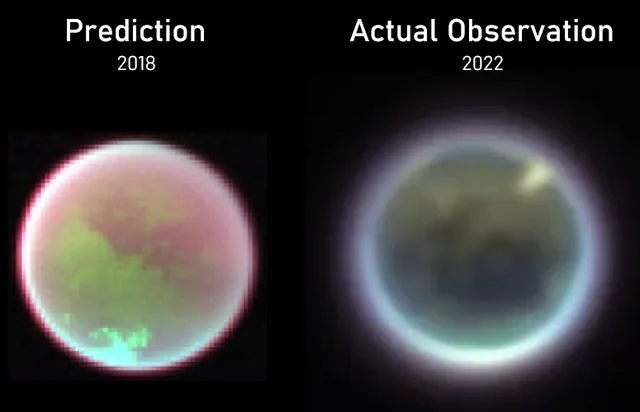

Quantum mechanics provides concrete evidence and empirical criteria for principles that have already served as foundational for the study of metaphysics, from the Ancient Greek era up until the modern scientific era of German idealism. We do not typically associate these eras with the development of quantum science, but the connection is indirectly historical.

If we examine the facts provided by quantum science, we will slowly, but surely, see that it is scratching the surface of what has always been the oldest and most fundamental principle of ‘idealism.’ It is almost as if the future is proving the statements of the past.

The usage of ‘idealism’ is not confined to a specialized discipline. Science overall, as a field of ontological inquiry, is by design an idealism. If metaphysical science accepts the notion that the world is fundamentally abstract, then the power of idealism is the force that causes reality to come into existence. The fundamental facts of quantum mechanics are, in essence, the same as the foundational principles of Metaphysics, with the former simply providing empirical evidence for the logic that has already been established by the latter. This lineage extends from the ancient Greeks through the idealism of Kant and Hegel, and continues into today.

These traditions constitute our central focus because they are considered the most successful in providing an accurate system for grounding the foundation of reality. The history of philosophy can be characterized as a series of attempts—some successful, some not—by philosophers to figure out the basics of Being. The contemporary thinker dealing with this issue must correlate the logical foundations of metaphysics with the empirical evidence provided by quantum mechanics. Our hypothesis is simply this: nature, at its most basic element, exhibits the exact same operations as the nature of Reason in the mind.

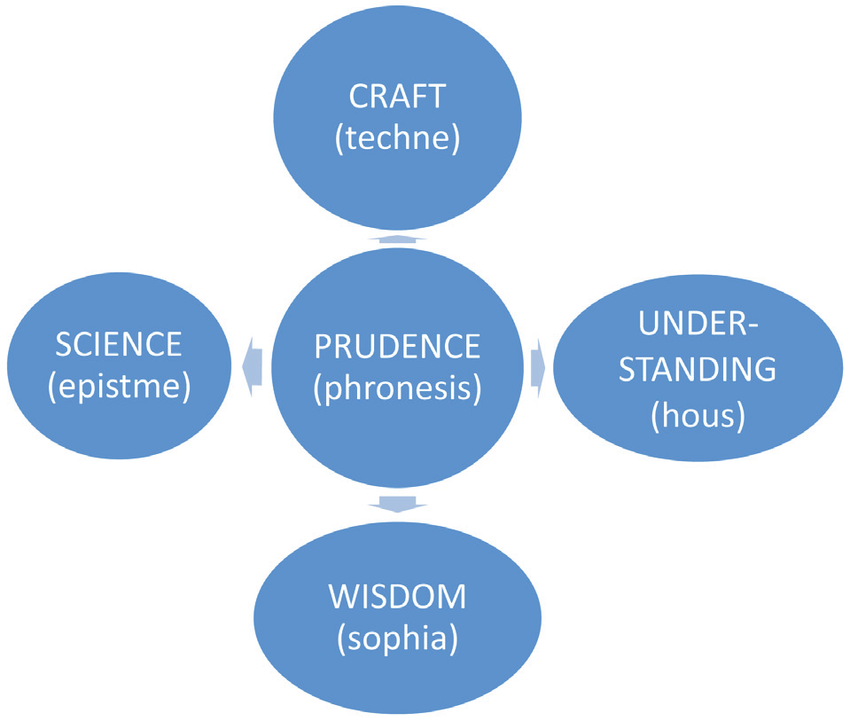

Reason is the unity between nature and mind, suggested by their interrelated meaning; the very reason why something exists, as opposed to not existing, is identical with its function or the structure it exhibits. Aristotle states that the purpose of the subject under discussion is related to the way it is physically built.

The purpose is not some untenable abstract aim, but has already been determined into being. The process after the fact is the realization of it—in other words, living through it. This is more complex than saying that the reason something exists is simply because it is ‘that way.’ The way something ‘is’ cannot stand alone, independent of the set of relations that presuppose its existence.

The Corruption of education

Some individuals conflate the value of a concept by crediting it with “completion” merely because it is taught in schools. However, the teaching of a concept is actually the process of validating it. Ideas are not “substances” taught in school. If school were a collection of universally true principles, then it should adopt its most ancient meanings. The modern application of “school” as a medium of learning is, in reality, disguised as indoctrination. In this latter case, “school” becomes a tool for implanting a specific idea into the minds of the masses—what Hegel refers to as the Weltgeist (world spirit).

Socrates, teacher-student paradigm

Socrates highlights a paradox in the teacher-student paradigm. He argues that the student requires a teacher, but the teacher was once a student who required a previous teacher, and so on. Moreover, just because a teacher is teaching does not mean he stops learning, and the student, by virtue of learning, is simultaneously teaching. This logic applies equally to the concepts taught in pedagogy. The fact that concepts are taught in schools does not make them complete; rather, in being taught, concepts themselves develop toward completion.

Difficulty of “teaching” and “learning” Quantum

These questions are especially relevant to the concept of quantum science, as it remains elusive for both teacher and student. The difficulty of quantum mechanics in modern times, even for those technically gifted in physics, stems from a lack of proper ontological foundation. Quantum mechanics is not only challenging due to its mathematical and scientific complexity; even materialist scientists who excel in physics and mathematics—those capable of applying quantum mechanics—often fail to grasp its philosophical implications. The science remains in its infancy because it has yet to ground its fundamental principles in the past knowledge established throughout human history.

The student of quantum science must therefore correlate past ontological knowledge with contemporary empirical evidence. In fact, this is precisely the resolution to Socrates’ teacher-student paradox: How is a teacher supposed to teach a student if the teacher himself is still learning? The answer is that the teacher has developed a foundational knowledge, appropriated from the history of human inquiry, to pass on to the student—allowing the student to update and expand upon it.

The distinctive task of the teacher, therefore, is to cultivate in the student the ability to appropriate a foundation of knowledge, from which the student can contribute their own insights and attribute value to it. The history of human thought is identical to the evolutionary capacity for reason that develops in individuals within their respective time periods. The teacher does not impart knowledge in a rigid sense but rather promotes the student’s self-learning tendency and stimulates the intellectual development of their era.

Animal – thinking and acting is one

———————

Abstract Thinking Is Counterintuitive

Abstract thinking is counterintuitive because it relies on the truth of its facts being prevalent, even when they are farthest from what is immediately apparent to sense perception. In the present moment, the furthest point from the immediate object directly in front of you is the truth of an abstract intuition.

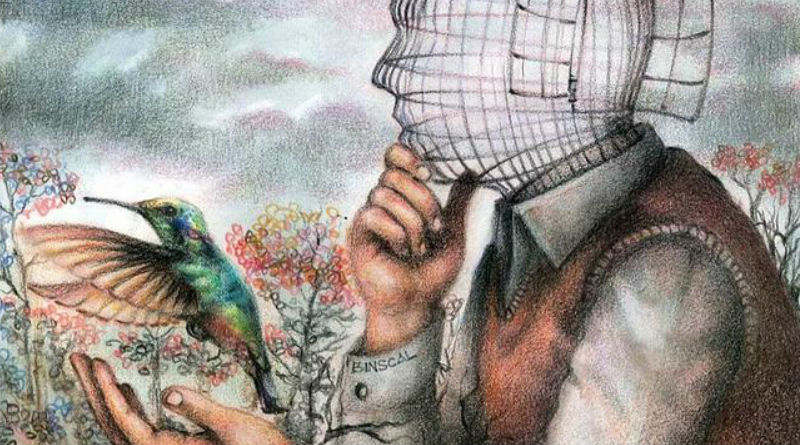

Animals are differentiated from human beings based on two observed facts:

- Animal consciousness is indivisible from the objects immediately present in their environment. The animal mind does not differentiate the world into distinct identities or categories; rather, its thinking is identical to what is presented through sensation.

- Animal thought and action occur simultaneously, with no clear delineation between thinking before acting or thinking after acting. Animals have such a strong focus on events directly in front of them that they do not distinguish their thoughts from their objects. Their thoughts and actions happen at the same time, and they instinctively act on their thoughts instantaneously. For example, if they are angry, they attack; if they are hungry, they eat; if they are scared, they flee.

Humans, on the other hand, deliberately refrain from acting on instinct, extending the time between thought and action to allow room for deliberation. For example, people may fast for health reasons despite hunger, restrain themselves from attacking when angry, or act courageously despite fear. In animals, the gap between thinking and acting is so narrow that they are indistinguishable—what they think and what they do form an identical experience. The idea of “thinking before acting” has no place in the animal world.

Forethought is an exclusively human trait, giving rise to the concept of the future and, consequently, anxiety. Humans rationalize the objects presented to their senses by separating what they think about from what they observe. The truth of abstract thinking operates independently of any particular sequence of time—just as a theoretical model remains valid regardless of whether it applies to the present, the future, or the past. A theoretical model is universal because it can be applied “now” in the present, “later” in the future, and “was” applicable in the distant past.

Animals are the true Empiricists’

The “crude materialists” argue that when a subject matter is furthest from sense experience, the abstract notion has no truth. They justify this claim by associating the most abstract principles with the most immediate instances of experience. There is nothing inherently wrong with this approach—if and only if they do not limit the most abstract principles (universal) merely to the modes or attributes of particular sense experiences (particular).

Sense experience restricts the possibility of understanding that events occurring in the present moment are not limited to that moment alone. How do you know that the present is not temporarily deteriorating? You do not—but you assume otherwise, and the inverse becomes the truer initial function.

The present is not reducible to the immediate moment occurring for sense perception. Hegel (paraphrased) states, “In this respect, the animals are the true materialists” because they do not perceive their thoughts as separate from objects. As a result, their thinking is limited to what they perceive. They are entirely reactive to the stimuli before them and automatically respond without deliberation. Humans, however, are the only known animals capable of forethought—i.e., thoughts occurring before or after an event.

What the crude materialists fail to realize—just as animals do—is that experience in the present consists of a set of abstract models. Taken individually, these models are theoretical; however, together, they form the concrete experience we perceive as the true moment. Materialists recognize only the latter but fail to see that the former is the actual true state of the present—namely, that the present moment consists of a simultaneously occurring number of parallel and potential events.

The observer determines a sequence of events into a linear duration of time, shaping what is experienced as a lifetime. In reality, these events occur simultaneously and in the same place, but the observer perceives only a single sequence at a given moment. From the perspective of the present, the future consists of an equally probable set of potential events, while the past has the asymmetry of having occurred in only one specific manner.

The question then arises: How do we determine the “desired” or “best” outcome? Animals lack a concept of the future, and therefore, for them, the future does not truly exist. What is true, however, is that the present extends into a duration of time by being constantly present. While animal consciousness is in flux—always changing, fading in and out of awareness—this is also true for humans. We exist only in the present moment, but when we sleep and wake up, our consciousness restarts, giving the appearance of a “new day.” We catalog these “new days” as the future.

As for what the future or past truly are, in both scientific and philosophical terms, that is a deeper question. The key idea here is that the “present” itself contains both the future and past as a set of ‘potential parallel’ events occurring simultaneously and instantaneously. However, the observer is inherently limited and cannot perceive this infinite process beyond the constraints of their own apperception.

Abstraction

The problem with limiting the most universal principles to the present moment relates to the problem of abstraction(s). In an ontological context, abstraction is the act of maintaining a complex system within a variable that is confined to a part. This partial view represents only an aspect of a broader whole—the whole of which is ignored, overlooked, and thus remains unknown and unpredictable to the observer.

A perfect example of abstraction is what Whitehead describes: taking an image of the sky containing stars and planets and assuming that it represents the entire, comprehensive view of the universe. This type of abstraction characterizes the scientific materialist outlook on the universe—an outlook that organicism ontology rejects, as it recognizes that mind itself is a substance in the universe, introducing an unpredictable element into the observation of nature.

The word variable has an interesting twofold meaning that appears contradictory but is actually complementary:

- As a noun, a variable refers to a specific component that is maintained as a distinct part, independent from the system that contains it.

- As an adjective, a variable describes something that is inconsistent, changeable, and unreliable.

Why would an element meant to be distinctly different from everything else be defined as inconsistent and always changing? Ordinary sense experience does not perceive the world as abstract thinking does. For example, classical mechanics aligns with sense perception in that it first identifies a result, followed by its movement. Consider a ball: the ball is the result, and its motion—such as moving to the left—is secondary. The ball must first exist before it can move in a particular direction.

Expanding this idea further, we see that there exists an infinite set of potential parts, yet only a confined and specific conception can disclose a finite amount of information. Within this conception, which defines an unknown and ever-changing continuous flux, there exists a finite and determinable set of objects. However, these objects themselves are in a constant state of change—they emerge and disappear continuously. While the process of degeneration and re-emergence is constant, it remains unpredictable in its specific details.

Classical Mechanics

Classical mechanics relies on a static notion of an object, asserting that if the present state of an object is known, it is possible to predict how it has moved in the past or how it will move in the future. However, the problem with classical mechanics in predicting the outcome of possible events is that it lacks the qualitative dimension of whether events ought to occur or ought not to occur at any given moment. The reason why an event occurs ultimately determines whether it occurs or does not occur.

The fact that potential future events all have an equal possibility of occurring does not mean they will all equally occur in reality. For example, in a purely quantitative model, the number of possible events is equal in that each event is represented as an individual numerical value. However, the kind of event that actually occurs depends on qualitative distinctions—specifically, differentiating between events considered “good” or “bad” outcomes. These measures are qualitative because they are relative to an observer. The occurrence of an event for the observer is not purely quantitative; it is evident that a number of events will happen to a number of observers, but the critical question is: what kind of events will happen, and to what kind of observers?

This question relates to a property in the observer known as the ethical principle—the idea that every outcome is either good or bad. Classical mechanics, however, strips away this dimension by reducing all events to their bare physical motions. In this way, we can analyze how the puppet moves while overlooking the puppet master.

A good outcome is not simply what the observer wants to happen, because sometimes the observer desires a bad outcome. Instead, the good outcome is what ought to happen. However, what ought to happen does not always occur; in fact, in most cases, it falls short of happening. Similarly, the bad outcome does not always happen because, whether consciously or unconsciously, the observer typically desires the best possible outcome—one that is always better than the worst outcome.

So, what future event is most likely to happen? The answer is that the event most likely to occur is the one the observer is most likely to deal with—either positively or negatively. This is a pragmatic answer because, if the outcome is to some degree determined by the observer, then the observer will determine an outcome that they are most capable of confronting. Whether they handle it well or poorly is another question. In other words, the outcome the observer learns (or becomes aware of) will be the event they ultimately experience.

Weakness of Empiricism

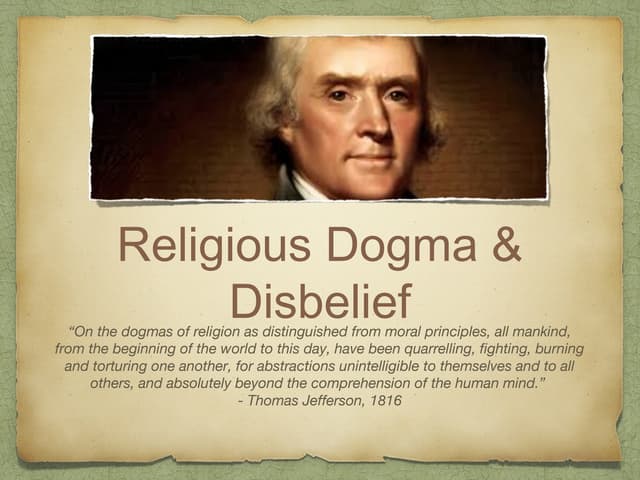

The weakness of empiricism exhibits the same problem as religious dogma—it is merely the other side of the same coin. While religious dogma makes the truth of God unattainable, empiricism collects endless information about the world without considering the ultimate purpose of those facts—it seeks the body without the soul.

The critique of metaphysics is often praised as a key feature of empiricism. Materialists argue that metaphysics makes claims about the world devoid of concrete facts. However, materialists themselves gather facts about the world without understanding their true meaning. As a consequence, they derive the wrong ontology from those facts, believing that ontology follows from the facts rather than preceding them. In reality, ontology is already preordained—it must simply be proven.

The weakness of empiricism is often praised as a skill, supposedly granting an advantage over metaphysics. Historically, however, metaphysics has always served as a critique of dominant modes of thought—whether religious or scientific. Its purpose is not to oppose these fields outright but rather to question them, ensuring they remain aligned with the true nature of reality when they begin to stray. The question of what truth is remains independent of the question of whether truth exists at all.

In the Ancient Greek tradition, Socrates employed metaphysics as a means of questioning religious thinking in order to better understand natural phenomena, including the nature of the mind. The mind, in this view, is recognized as the first element in nature. Throughout history, metaphysics has been used to challenge foundational ideas about the universe, including preordained notions of God. In religious thought, questioning the nature of God has often been considered blasphemous. A less dogmatic interpretation holds that God can never be fully understood, because once the nature of God is stated, that description ceases to be God in the absolute sense. The notion of God is an absolute truth that transcends any finite definition.

This idea is not in itself incorrect—there is always a greater conception beyond any single conception. However, the problem arises when that “greater” conception is rendered inaccessible due to rigid and finite definitions. There is always more to a fact than the fact itself. The mistake in viewing God as the absolute limit of knowledge is that this limit is not treated as a feature of the world but as an obstruction to inquiry. Thought reaches a dead end upon recognizing this supposed limit, forcing individuals either to submit in worship or to retreat into vulgar materialism, endlessly accumulating facts about the world without recognizing their broader unifying significance.

The dogma of religion makes God the limit of knowledge, while the equally extreme dogma of vulgar materialism seeks knowledge without any concern for its ultimate purpose. Both of these distortions make truth seem unattainable: in religious dogma, truth is unreachable no matter how far one reaches; in materialist dogma, truth always slips away the moment it appears grasped.

Religious thought has historically been corrupted by its rejection of ontological inquiry, which seeks to understand the fundamental nature of the universe. Instead of serving its true purpose, ontology has often been reduced to a means of reaffirming religious worship. In this framework, understanding God is deemed sinful, while fearing God is considered the foundation of wisdom. However, if knowledge is not a sin but a responsibility, then faith itself depends on knowing the word of God—which, in turn, is identical with what God is.

While the vulgar empiricist rejects God altogether, for them, the world is lifeless—a never-ending, dead place without purpose. Our creation is seen as a mere mistake, an accident that we must deal with by searching for facts that only satisfy our most immediate needs. A materialist is like a hound sniffing around for an object; upon finding it, the hound continues sniffing without understanding why it is searching. The police officer, however, uses the hound to find evidence. For the dog, it is a simple exercise of its dominant sense—smell; for the police officer, it is the use of his mind. Empiricism in this sense is like the hound, while ontology is the officer.

Dogmatism

Metaphysics has acquired the widespread misconception that it is a form of philosophical thinking aimed at supporting dogmatic views, rather than questioning them. In other words, metaphysics today is conflated with dogma, which is unfortunate because it was originally designed to counter-check dogmatism. The dogmatist, in their rhetoric, conflates the term ‘metaphysics’ with ‘dogmatism.’ The very system intended to counter-check dogma is now associated with it, allowing the dogmatist to go unchecked—something they ultimately rely on in order to make ungrounded claims. It makes sense that a dogmatism would seek to eliminate any fact-checking system to maintain its falsities without being questioned. This misconception has persisted in the minds of ordinary people, who no longer define metaphysics as scientific but instead view it as mysticism.

Metaphysics was originally created to check false claims about the universe because it is the primary science that requires a logical basis for truth. Dogmatism corrupts metaphysics because it seeks to make its claims immune to logical scrutiny. Academics today are in disagreement about whether logic is universal or artificial. If logic is artificial, they can create their own man-made systems of verification to maintain their dogma. However, if logic is universal, then it is an organic system discovered by mankind, and humans must answer to a rationality that exists outside themselves, rather than relying solely on their own reasoning. If universal logic does not exist, then their facts can go unchecked.

Ironically, it is the very reference to outside rules and laws that the dogmatist claims to be ‘objective’ that they use to justify their subjective claims. Historically, dogmatic religious thinkers have referred to God to justify what would otherwise be inhumane actions. They make knowledge of God the absolute principle ‘beyond’ the mind. The combination of ‘absolute’ (which cannot be questioned) and ‘inaccessible to the mind’ (beyond comprehension) is the fatal mark of dogmatism. That is, God is made the limit of thinking. The subjective opinion is disguised as an objective truth with ‘no’ inherent truth other than personal gain, because God is said to be interpreted only through personal understanding.

Monotheistic religions have attempted to make an objective claim about God, but in doing so, they have made God the objective limit of knowledge. Consequently, any notion about God is merely a limited interpretation based on an individual’s finite understanding. In other words, God can no longer necessarily be said to exist if all our notions about Him are just interpretations of something we cannot absolutely conceive, yet at the same time, we are conceptions of this being.

Error of Idealism in Empiricism

If truth depends on the objects outside the mind, and not the mind “inside” the object, then the conclusion is that; whatever the “subject” (the being) perceives constitutes the absolute basis for truth. In other words, truth is subjective. The latter claim, as we repeatedly show, has many issues when considered as an absolute ontological principle.

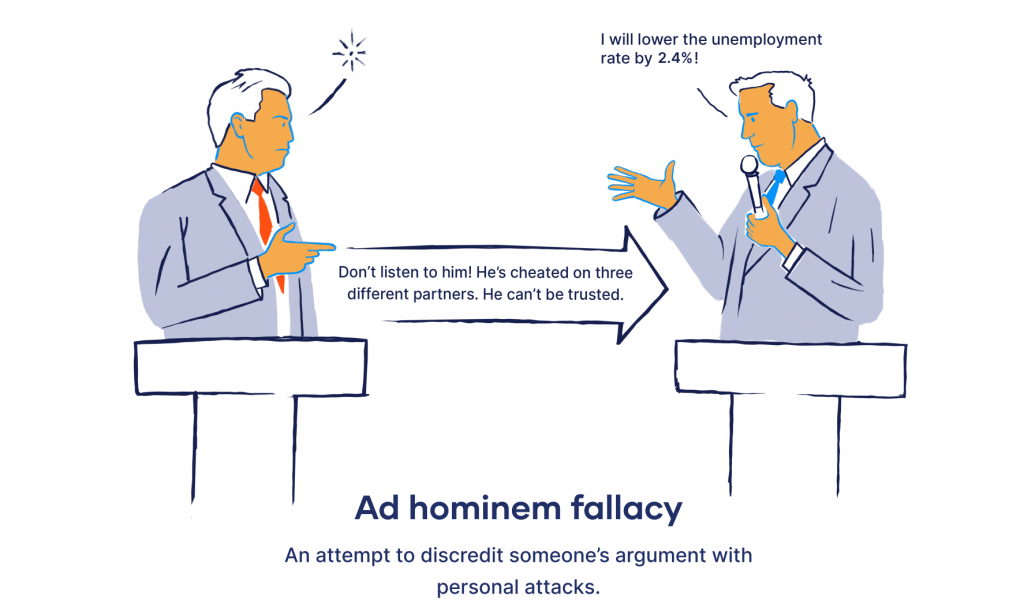

The kind of logic that empirical science purports to have requires the negative connotation associated with idealism. The mischaracterization of what metaphysics is – a straw man argument. What empirical science fails to realize is that they completely misunderstand idealism, reflecting their own biases as truth.

This kind of logic fails when it confuses the property of empiricism by applying it to the nature of idealism. Looking at an object and then concluding that whatever is observed is the indubitable fact about it; is the same narrow thinking as the opposite claim, which states that any form of thinking is true by virtue of it being thought of, that is, whatever I think, is true. The empiricist says that the latter does not hold up like the former, so the field of idealism is erroneous. However, this supposed error in idealism is, in fact, the blind spot of their own error, which they fail to acknowledge.

The standard of empiricism is used as a measure to claim that idealism is false, but this so-called “false” aspect of idealism is precisely the problem with empiricism. In the most basic terms, the common initiation goes like this: “It is what it is”—which is counteracted by the other equally viable initiation: “Nothing is what it seems.” Both of these are equally incomplete, coming from two opposite perspectives. They are initiations because both make an affirmation of something positively being there, 1) “It is what it is,” which affirms that something undeniably exists in a certain way, and its opposite, 2)“Nothing is what it seems,” which affirms that reality is ultimately deceptive or unknowable. Both of these affirmations make a positive claim about the nature of reality, yet they are equally incomplete, each coming from a different end of the spectrum.

The problem is that every science thinks they are dealing with different types of substances because they believe there is only one fundamental substance, and anything else is secondary to it. For example, materialists say that matter composes all things, while mathematicians say that numbers are the root of all things, and philosophers say that mind (Reason) is the universal substance. They are all right, but not in the same way. In other words, they are right, but not in the same order. Philosophy is more fundamentally right than all other forms of thought because, first, you need to establish a correct ontology, i.e., worldview, before you can understand anything in the world and the facts about it.

Anselm’s “God” Argument (part 1)

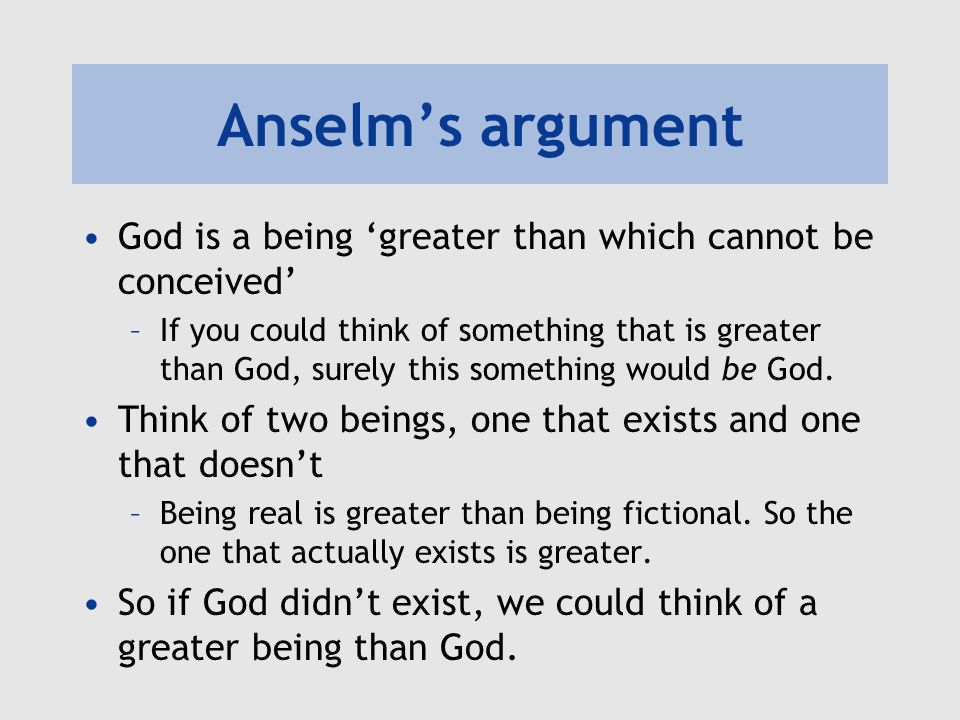

Anselm’s ontological argument for “God” serves as one fundamental example of the misapplication of metaphysics. The argument follows as such:

“God is a being than which none greater can be imagined. A being that necessarily exists in reality is greater than a being that does not necessarily exist.”

If you can imagine God, then by definition, He is NOT the greatest because He is less than the being that imagines Him. The ability of a lesser being (in this case, the human) to imagine God means that the lesser being would be greater than God, who is being imagined. If a being less than God can imagine Him, this would make God NOT all-powerful, but a fallible being. The second part of the argument is crucial because it suggests that God is not only a being imagined by humans, but also exists in reality outside of them.

The assumption is especially interesting because of its use of “inverse logic,” where the conclusions are presupposed in the beginning of the argument as the first premise, so that the premises leading to the conclusion will make it true. The first part of the argument leaves ambiguous whether God exists only in the imagination of the human or whether God exists outside of the human mind. Yet, it still concludes that God cannot be ultimate if He is only confined to the human mind. Therefore, God must exist outside of reality in order to be truly labeled ultimate.

The conclusion is that God is never only in the mind of humans, but exists in reality. Since what exists in reality is more “real” than what does not exist in reality, God is only real if He exists outside of the human mind, and not real if He exists only within the human mind. The argument is, in fact, ingenious because it utilizes the essence of logic as a system of structures and order, rather than focusing on content or meaning. The placement of God within the human mind, as opposed to God existing in reality outside of any mind, is a valid logical structure. This is because both presuppositions—reality and the human mind—are assumed beforehand as invariably true, and the conclusion follows logically from them.

God is presupposed as the ultimate principle. Whatever that ultimate principle may be, it is named God, and if its nature is true by definition as being ultimate, nothing else can surpass or contain it. The presupposition that God is ultimate is a principle grounded on the fact that there is always an ultimate principle. Whether we know its finite nature or not is a separate question from maintaining the necessity of an ultimate principle in relation to finite variables.

Anselm’s argument is Secretly Materialist (part 2)

The argument relies on the claim that: (1) God is a being than which none greater can be imagined, and (2) God cannot be fully accessed by the intellectual powers of humans. This argument presumes that God is an invariable part of the mind, as it serves as the limit of knowledge. At the same time, it is independent of the mind due to the very limitation of human thought to access it. While God exists in the mind, He also invariably exists in reality “outside” the mind, because we say God is an independent being who serves as the “ideal” of nature, possessing absolute power, matter, and energy.

The logic follows that, if something can be conceived in the mind, it must first already exist in reality outside the mind. This line of thinking implicitly presents materialism disguised as idealism. God contains the entire content of the universe and the “more” potential beyond it. This abstractionism leads to the same infinite regress problem that materialism suffers from: beyond a certain point—call it “God” or “singularity”—there is redundancy in the recurrence of the same unknown variable multiplied beyond a measure. There is always “more” of matter to discover, or “God” becomes that one aspect we can never fully uncover. This is the negative of the positive affirmation in Anselm’s argument for God, which states:

“A being that necessarily exists in reality is ‘greater’ than a being that does not necessarily exist.”

The assumption is that humans do not necessarily need to exist for the universe to continue existing, whereas God must necessarily exist for the universe to be conceived. This latter point can be interpreted to mean that, although individual consciousness or a limited mind may not necessarily need to exist for reality to continue, the opposite must necessarily be true: consciousness or mind, in the absolute sense, must necessarily exist for the world to “be,” because the existence of the universe depends on an observer, be finite or ultimate, one or the other. According to quantum science, the observer phenomenon is indivisible from any material cause. At the fundamental level, even of matter, there must be an instrument of observation, a substance of mind, that must be present in order for the physical phenomena to unfold and take on a sequence of events that describes its mechanics.

The key term in this proposition is “necessarily,” because God is assumed to necessarily exist due to the fact that the entire universe depends on God—the universe being a “conception” from God. The universe as a “conception” of God means two things: (1) God “conceives” the world mentally because conception is the mental phenomenon of creating or “realizing” something into being i.e., consuming the object from the outside into the inside of the mind, and (2) “conception” more generally refers to the actual generation of an object into physical being. The reason for the latter claim is that the human mind is limited to the information it receives from the outside; it cannot go beyond the data it receives. In other words, it can only receive from the outside, and the assumption is that it cannot generate its own data into being. If it does generate its own data, then that truth is also limited because there is more information it did not fully access from the outside, but it only receives what it can to form the picture of reality, a resolution to the complex problem.

Once the notion of God is conceived in the mind, a more perfect notion of God exists outside the mind. This results in a conceptual infinite regress regarding the notion of God: whenever a subjective understanding of God is achieved, a more perfect objective understanding always exists. Once the notion of God is attained, it is no longer perfect. This makes the mind always fall short—always imperfect—because it either cannot keep up with the infinite matter outside of it, or it cannot keep up with its own substance, a greater version of itself, God that it cannot conceive. The subjective and the objective do not bear a direct relationship with this logic, or if they do, their relationship is merely this: the subjective is flawed, and the objective is true. The separation between them constitutes their relation. This fails to conceive how the subjective is the expression of the objective, which is the very predisposition to the notion of ‘man as created by God’ in the Bible.

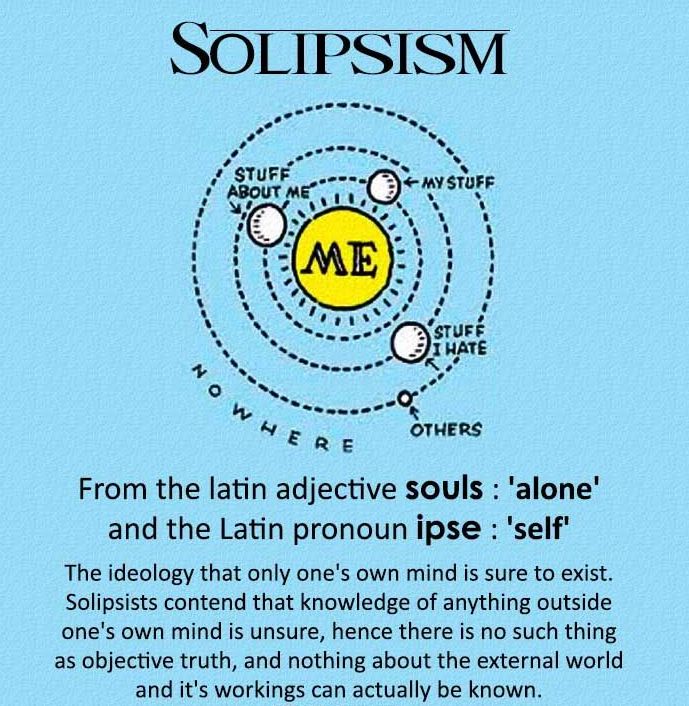

Solipsism

If the principles of solipsism are carried to the extreme, it would present a problem for Anselm’s argument.

Solipsism is the opposite view of Anselm’s argument for God. It assumes the opposite—that there is no God, and only the “self” constitutes ultimate reality. Let’s explore how this is false, or in concrete terms, an illusion.

Anselm’s argument conceives the existence of God by claiming that because God exists in the mind, God must also exist in reality. This excludes the predicate of such thinking: that because God exists in reality, God must also necessarily exist in the mind. The existence of God does not first have its place in reality; rather, the existence of God derives its reality by existing in the mind. The notion that ‘something’ is the way it is because “it” exists in the mind can lead to a kind of intellectual psychosis, where the thinker assumes that whatever he “thinks of” will manifest in reality simply by virtue of being thought. This can resemble a type of paranoid personality disorder.

Solipsism takes whatever is “true” in the mind to be invariably “true” in reality “outside” the mind. It is based on the assumption that whatever is “seen” in reality is also invariably an existence enclosed by the mind. The mind encloses reality wherever it perceives it, therefore “where” is the reality independent of the mind that encloses it? Without the mind that perceives (or conceives) the world, the world would not be known. Therefore, wherever there is reality, you must also presuppose the mind as an indivisible principle from reality.

Reality outside the mind depends on the mind that conceives it. From this indivisible relationship between mind and reality, solipsism makes the further crude (extreme) conclusion: Since the world depends on the mind in order to be perceived, the world would not exist if it were not perceived by the mind. Therefore, whatever the mind perceives must be reality. The latter is the problematic conclusion.

The essence of solipsism is logically true; it is only the later finite conclusions it makes that become erroneous. Unlike Anselm’s argument for God, the conclusions following solipsism’s premises are not universally true because the first presupposition is that the mind is ultimate. In contrast, Anselm’s argument presupposes that God is ultimate. For solipsism, the mind is not ultimate, but rather fallible and finite. Therefore, not everything the mind conceives in reality is automatically real. There is a fundamental contradiction in solipsism that is not necessarily present in Anselm’s argument. Namely, God is ultimate, while the mind is not. For solipsism the mind is ultimate but there is no God?

God is the essence of mind, namely, mind has an aspect of it that is ultimate, but as a concept it is also finite. However, God the ultimate aspect of mind, cannot inherently be finite, but must be inherently unlimited, it cannot be accessed by mind that is limited. God is that one aspect that is not accessed by mind, yet must logically and necessarily be true, even for mind. The next question is: when can we presuppose that the mind is ultimate? We know the mind cannot truly be ultimate, as it is fallible and finite in its observations of the world, but when can the mind be considered ultimate? Or, in other words, what aspect of the mind is ultimate that justifies its indivisible place in relation to the world, such that reality depends on it?

Solipsism does find value in the quantum sciences if we claim it as an epistemological position. As an epistemology that is not divorced from a proper ontology (metaphysics), solipsism makes two distinct yet contradictory points: (a) anything outside one’s own mind is “unsure,” and (b) the external world and other minds cannot be known and might not exist outside the mind. The fact that reality outside the viewpoint of one’s own mind is uncertain does not necessarily mean that it does not exist or possess its own self-subsisting existence. In fact, in materialist ontology, it is assumed that all objects are entirely distinct and separate units with their own identities, holding their own ground against each other.

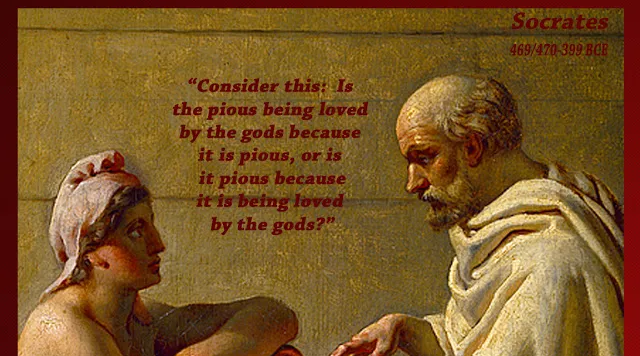

Euthyphro Dilemma

Metaphysics inquires into the fundamental nature of things precisely to break away from this (solipsism) kind of logic. The Ancient Greek tradition, for instance, was among the first to apply metaphysics in a scientific form, seeking to understand the fundamental nature of the object rather than just what is said about it. This is where the scientific predisposition toward metaphysics began, prior to its later theological misapprehensions.

Aristotle defines metaphysics as the “first philosophy,” dealing with the fundamental principles of nature. Ontology, a branch of metaphysics, deals with abstract principles such as Being, Substance, time, space, etc. Socrates’ condemnation to death was precisely due to his questioning of the primary nature of God. Socrates commits the blasphemy that Anselm’s paradox addresses—a paradox that presents an impossibility, one that cannot be committed even if one tries. However, for the state, they punish the questioning of God. The pragmatic consequences of the theoretical. For Socrates, he was attempting to achieve the impossible, the discovery of God, which ultimately caused him killed. For example, in the Euthyphro, the dilemma is paraphrased by Plato as follows:

“Is that which is holy loved by the gods because it is holy, or is it holy because it is loved by the gods?”

In other words: (1) Is the Good… the Good… because God said it is Good? Or (2) because it is the Good, God said it is the Good? The latter presupposes that the Good is outside and independent of God, and therefore there is something higher than God, which God only applies. In this case, God loses his value as the ultimate principle of the world. God is not the absolute principle if something is higher than Him.

The first point makes God the standard of the Good because whatever ‘He’ commands is the Good. If the first part of the dilemma is true, then the Good can be any arbitrary measure made by God, and therefore there is no real standard to say something is good or not, other than the arbitrary command of God. If the second part of the dilemma is true, then there is no God, because there is a standard higher than Him—i.e., the Good—and there is also no ultimate standard of the Good because it has lost its absolute or universal force of execution, i.e., God. The impossibility is that, God is without the Good, and the Good is without God.

The solution to this age-old dilemma is somewhat solved by the Christian tradition with the notion of the “Trinity” — the “Father,” the “Son,” and the “Holy Spirit.” The Trinity, in its essence, argues that God is a threefold substance: (1) God the “Father” is a figurative abstract, a potential, or an ideal; (2) God as Christ is concrete matter, flesh, and a finite individual body; and (3) God as the Holy Spirit is the translation between the abstract and concrete, the ghost, spirit, or ether that holds extreme opposites together into a unifying form. The relation between God and man is spirit (classically translated as mind).

Idealistic

The abstract notions of ontology are often identified by empirical science as idealistic or belonging to idealism. Scientific materialism argues that “abstract notions” exclude the nature of ‘physical reality’ and that their existence is unrealistic because they do not possess “concrete reality.” However, this definition of “concrete” reality excludes its own abstract notion, which makes sense of it.

Ironically, materialism, in trying to provide a concrete basis for everything, provides the most abstract notion of all: “matter”. There is no such thing as “matter” existing independently as a substance external from the objects that are identified as “material.” Matter, in other words, is a wholly abstract notion on its own and does not exist as a single substance. Rather, matter is a generalization of things that are alike in their capacity to be observed (or sensed) by the observer. Matter is an aggregate collection (aggregation) of related qualities for an observer.

Empirical science seems to understand Metaphysics in the same way it is defined by religious thinking. Just as religion defines metaphysics, empiricism views it in the same way. It is easy to claim that abstract notions possess no concrete reality because that serves as justification for not inquiring into the nature of them—precisely the kind of justification that is valid for empirical thinking.

The vulgar materialist possesses the following logic: because first principles possess no immediate concrete reality, i.e., they are not objects, they are wholly theoretical and abstract, and therefore do not exist apart from the objects we directly observe. The objects we directly observe are the only “true” foundation for existence, according to materialism, and they should only be explored to the extent that they can be sensed. Even if they can be “thought” of (sensed by the mind), that is not enough criteria to constitute them having reality.

Empiricism justifies not dealing with thoughts as objects, focusing only on things that are immediate for sense perception. This intellectual shortcut is adopted by empirical science. The nature of first principles is difficult to understand because they are the furthest substance from the senses. This means they can only be grasped by so-called “abstract” or “theoretical” thinking. Theoretical thinking is however a physical endeavour, but it is not sensed.

The idea that first principles are theoretical is not a problem in-and-of-itself. The empiricist argues that they are defects because they are not observable by sense perception. Yet in every science, finite “numbers” are purely abstract; however, they constitute a true representation of all physical objects. The true problem with empiricism is that it lacks the foundational truth of idealism, which is that the fundamentally true nature of the objects observable by sense perception is that they are inherently “abstract models” of the Form they exhibit. This Form, whether abstract or not, is not answered by the representation of objects, but we must find the original source of the representations that present themselves as immediately real.

Concrete Principles

First principles are precisely meant to be “difficult” because they grasp the nature of total reality, which sense perception can only capture in a limited way. The assertion that first principles do not possess “concrete reality” because they are not perceived as objects that are “normally” perceived falls into a theoretical error, failing to properly associate first principles with the principle of the concrete (the fallacy of misplaced concreteness). How is the concrete nature of reality a first principle? In other words, what is the first principle of being “concrete”?

The “fallacy of misplaced concreteness” happens when the thinker commits the error of confusing the nature of the concrete. This fallacy, which we explore more deeply in other sections, assumes that the “concrete” is only “real” when it is separate and constitutes a more fundamental position in reality than the abstract, which is said to be elusive, theoretical, and unreal. The correct remedy to this fallacy is to find the abstract in the concrete, or how the abstract itself constitutes a concrete basis for reality. Where he places the principle of the concrete is the area where the error occurs. If for example, he says that all matter is concrete because the concrete is matter, then he commits the fallacy by presupposing the conclusion prior to the premises. The fallacy does not make the conclusion into a premise, and therefore the conclusions cannot be stated, as they do not achieve a truth outside of the original presumption.

A part of this scientific fallacy is the mindset that places ‘no belief’ in the universe bearing “Reason” outside the human mind. In other words, the world “out there” is random and chaotic, while the mind “in here” is rational and ordered because it makes sense of what is otherwise incoherent. This common-sense proverb has twisted and confused the placement of true reality. The inverse is equally true: the mind within us is chaotic and unpredictable, but the world “outside” the mind, according to elementary mechanics, exhibits a definite and predictable set of determined interactions.

“Fear of falling into error”

Not believing in the “Reason in the world” is induced by a “fear of falling into error,” which introduces a distrust into science. According to Hegel, the “fear of error is the initial error… and is the fear of truth…” (Mind 28-29). Hegel writes:

“Meanwhile, if concern about falling into error injects a mistrust into science, which, without any such misgivings, gets on with the job itself and actually cognizes, it is hard to see why we should not, conversely, inject a mistrust into this mistrust and be concerned that this fear of erring is really the error itself. In fact, this fear presupposes something, a great deal in fact, as truth, and it supports its misgivings and inferences on what itself needs to be examined first to see if it is truth. That is to say, it presupposes representations of cognition as an instrument and medium, also a distinction between ourselves and this cognition; but above all, it presupposes that the absolute stands on one side and cognition on the other side, for itself and separated from the absolute, and yet is something real or, to put it bluntly, it presupposes that cognition which, since it is outside the absolute, is surely outside the truth as well, is nevertheless genuine—an assumption whereby what calls itself fear of error stands exposed rather as fear of truth.” (Phenomenology of Spirit 74)

Ignoring the importance of first principles is detrimental to the very task of empirical science itself. Once the set of concrete facts are derived about any particular phenomenon in the universe, what do these facts pertain to? What nature of reality do they reveal? What is the relationship between the particular facts about nature and ultimate reality?

Empirical science fails to deal with first principles. It will simply claim that empirical facts are either true in-and-of-themselves or are true in terms of their particular “external relations.” These sets of empirical facts are true in terms of the phenomenon as it appears, not as it is in and of itself. The distinction here is that there is always something in the phenomenon that does not appear.

The facts about external relations produce their own ontology. It is the ontology that sees nature as nothing else than what it “appears” to be. True facts about a particular natural phenomenon, however, only indicate that such facts pertain to the phenomenon, rather than explaining what the phenomenon is. The definition still does not target something independently true outside of its relations.

The task of empirical science is to derive the infinite set of facts without the purpose of their knowledge, or only knowledge of them without purpose. The failure to apply first principles in relation to facts does not mean that each set of particular facts must immediately be related to the utmost general and universal principles of Being. Rather, there are first principles implied in each and every particular fact about a specific topic.

Obeying a Formal System

Academics usually claim that “reasoning” is correct when it is consistent with a formal system.

A “formal system” is a composed, manufactured way of thinking; ready-made so that the maximum number of people can apprehend it. Formal systems are usually consistent with common sense or with what our natural organs of sensation provide as ordinary experience. What we mean by “ordinary experience” is consistent with a mechanical way of doing something without the need to reflect on it. As they say in the office, “crunching numbers” describes a repetitive and mechanical human activity. In this activity, the individual has to entirely rely on and obey a formal system.

In order to achieve knowledge of how particular facts relate to the most universal principles, knowledge about the “first principles” concerning the facts themselves must be achieved. To this extent, it is important to understand the true definition of “idealism” (Science of Logic, 48). Hegel, for example, is misunderstood as an “idealist” because he is widely criticized for his “informal” writing style.

Academics claim that nobody “understands” Hegel, and therefore, if his way of delivery is flawed, then he has nothing truly valuable to say. However, Hegel is only “difficult” to understand because he is employing an informal way of thinking, a different system of logic NOT commonly shared by most people. He is NOT formal, but being formal does not necessarily mean being correct. Hegel lays out a series of contradictions that lead to valid conclusions. We are both the medium and instrument of the thought process because we use it and then deliver through it.

It is actually the formal system of logic that inverts the natural way of thinking, i.e., informal logic, and claims that the opposite of the truth is, in fact, the truth. The natural way of thinking is always informal because it does not conform to a specific, confined system of abstracting the world. But this does not mean that there is no objective system for understanding the world, nor does it mean that each individual’s subjective system of understanding the world is equally true in depicting the objective nature of the world.

How to Misinterpret a Philosophical Work

People usually misunderstand a work of philosophy based on the following mistakes. Common mistakes take the form of: 1) individuals who have NOT read the work and are talking about what they think (“assume”) the work is about; 2) they get their understanding of the work from others, who already have a biased opinion about the work; 3) those who have read only parts of the work that they want to read, or the sections that seem to tailor to their already preconceived opinions about what they think the work is about; and 4) lastly, they “cherry-pick” passages that are taken out of context so they can show the whole of the work is flawed. All these instances are variations of “straw-man” fallacies implemented against the philosophical work.

The reason why it is especially important to read a philosophical work in “full” is because, over time, the reader will recognize the dialogue the philosopher has with his own mind. Hegel’s notion is metaphysical because it is grounded in abstract truth, so as to develop the theoretical; whereas empirical science is the elaborative stage after that, which applies the theoretical to produce the concrete. The materialist claim that by beginning with the concrete, they possess a concrete principle. However, any true philosopher (or scientist) knows that the first concrete principle is the abstract. The abstract is the first true notion of the concrete because it is proven theoretically, and it is this fact that constitutes the reality of empiricism, which it does not dispense with.

Where does empirical science derive its theoretical methodological system if NOT from the place where such a system already produces the concrete? Empirical science derives its formal system of logic from an already informally conceived system of logic. But because it is informal, it does not receive the same “fame and recognition” as the constructed and furnished formal system of logic. But just because it is not recognized with the same fame does not mean it lacks existence as the predicate. It cannot forget, nor operate as itself, without its predicate, without the very source of its theoretical truth, which has already been derived from the concrete. According to Hegel, every science is itself idealistic… (Science of Logic).

Beyond Sense

The point of stepping beyond the “mundane” is to recognize that even the natural organs of the understanding do not arrive at truth through standard methods of “correct” reasoning. Our sense organs perceive an “ordinary” world by filtering out aspects of nature. For example, vision limits the world to discrete moments of abstractions that characterize a more general relation (or happening). Touch, on the other hand, focuses sensation on a localized spot. You never feel the total surface area of an object, but only specific areas (sections) of it. No matter how large or small the object is, touch can only “feel” the localization of a surface area within a “general” field, which exists beyond the reference frame of the observer (beyond the faculty of touch). Sight, similarly, can only perceive the general outline of that surface area, not its complete depth—such as the radiations of light, the speeds of energy, or the complete gradients in material.

Ultraviolet radiation has a wavelength shorter than that of the violet end of the visible spectrum, and cannot be observed by the faculty of perception without the aid of instruments. Yet, color is naturally perceived, and the sense of touch can independently detect heat from light. Ultraviolet radiation is a fundamental source in nature for both color and heat. Our senses detect heat or color independently through their specialized faculties and claim that each originates from its respective source. However, in truth, both of these senses are derived from the same fundamental source.

The zeroth law of thermodynamics states: “If two systems are each in thermal equilibrium with a third, they are also in thermal equilibrium with each other.” This is essentially a logical rule: if heat and light are distinct forms of energy, they are still interconnected. That is, you can derive heat from light and light from heat. In fact, both heat and light are fundamentally forms of motion. For example, in atomic theory, heat is simply the result of atoms being stimulated by friction, causing them to move rapidly in place. But the establishments of both heat and light need to be explained from their informal side, which cannot simply be accepted as readily available knowledge. Why, for example, do rapidly moving atoms at a constant rate produce a felt phenomenon like fire? This question goes deeper than what science can explain. Why does fire appear as a red, wave-like stream? The physical explanation is different from the subjective, felt experience.

True facts that belong to improper Ontology

1.7 “Proper” Ontology

The difference between “proper” and “improper” ontology is not a matter of distinguishing between what is true and what is untrue. In other words, both truths are not equal. The fact that different opinions can be true is true only in the sense that they both exist. However, the second fact—the nature of their existence—determines their inequality. The “equality” between ideas does not imply that they are equal members of the same quantity; rather, their quality defines how one is above the other. This should not be taken in an ethical sense—i.e., one person being superior to another. Although, even within the human domain, we observe a hierarchy, where people are structured in a systemic chain, with some being superior in terms of class, body, mind, genetics, etc. Any of these qualities exhibit such variations in degree that they result in an unequal distribution of individuals across the species.

The species is the actual distribution, the substrate spread across an aggregate of spacetime known as “the planet.” Beyond this macroscopic sphere is an internalized, microscopic dimension, extended infinitesimally to disclose experiences we identify as “abstract” (like atoms) or “thought”. How does Being restore itself after falling short of itself, missing itself into death, which is the moment of non-actuality for the being. However, Being continues after this opposite moment of itself. Being is absolute; it rediscovers itself always in order to maintain the meaning of being rather than not-being. Hegel explains below the transition from Death to Being.

“Death, if that is what we want to call this non-actuality, is the most dreadful thing, and to hold fast to what is dead requires the greatest force. Beauty without force hates the understanding because the understanding expects this of her when she cannot do it. But the life of the spirit is not the life that shrinks from death and keeps clear of devastation; it is the life that endures death and preserves itself in it. Spirit gains its truth only when, in absolute disintegration, it finds itself. It is this power, not as the positive which averts its eyes from the negative, as when we say of something that it is nothing or false, and then, finished with it, turn away and pass on to something else; spirit is this power only by looking the negative in the face and by dwelling on it. Dwelling on the negative is the magic force that converts it into Being.”

The difference between “proper ontology” and “improper ontology” is not in the “content” of thought but in the way of thinking—the form of thought. We cannot assume that gathering a bunch of correct facts and calling this process truth is sufficient. There must first be a true presupposition, which is the conclusion that these gathered facts prove. In other words, the facts must be “saying something,” pointing to a worldview. The worldview makes sense of the facts; otherwise, they remain empty abstractions. The intent behind the facts is what determines a proper ontology.

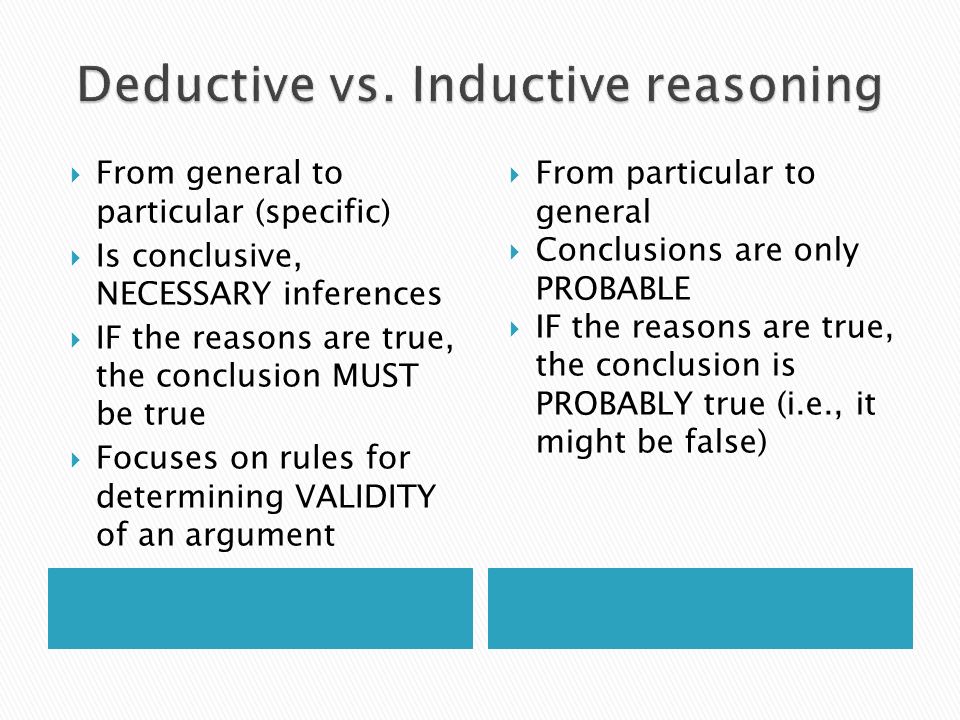

Necessary vs Probable Conclusion

What makes an ontology ‘false’ is different from what makes other forms of knowledge false. For example, in analytical knowledge, a fact can be false, but the belief or worldview may still be correct. Conversely, if the worldview is false, correct facts cannot belong to it because they would be inherently inconsistent or misused. The worldview is the foundation upon which truth follows; it guides the facts toward rational conclusions and has therefore a moral principle. By “rational,” I mean “that which makes sense”—it can be deduced logically, i.e., it can be made sense of.

Aristotle says that anything we know is scientifically true when the “necessary conclusion is just as certain as its premises, while a probable conclusion is somewhat less so.” For example, we can scientifically know that the three internal angles of a triangle add up to two right angles. This fact is characteristic of technical knowledge found in analytical truth and is either the case or not—it is necessarily true, and cannot be other than what it is in order to remain itself. The opposite, which is “probable” truth, can include two contradictory facts existing together at the same time. These logical “rules” are also observable in nature, which is a rational system.

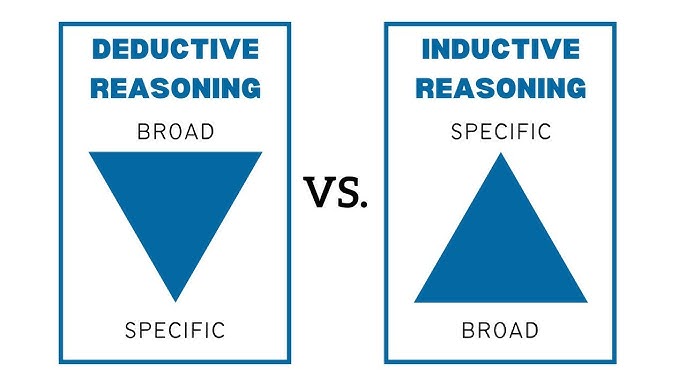

The dimensional degree of reality is determined by deductive as opposed to inductive reasoning. In the deductive sense, we must deduce (arrive at) reality on a microscopic scale. The microscopic scale is arrived at by deduction, assuming that if reality on a macro scale is necessarily true (by direct perception), then the microscopic scale is also true by its indirect relation to that former fact—i.e., from General to Particular (specific). We arrive at the microscopic, infinitesimal (minute) state of time through the macroscopic scale of reality. For example, from the generality of spacetime, at the most infinite scale, everything is revealed to us as minute points in spacetime.

Conversely, if we “induce” reality by way of inductive reasoning, we are presupposing the following: If ‘from the particular to the general’ means the higher you go out into space, the larger the scale becomes, then the larger the scale, the more “probable” reality becomes. In other words, reality becomes more “probabilistic” at the infinite scales, which also means infinitesimal. The more “probability” we observe, the further we go into both the most macroscopic and the most minute and infinitesimal scales. For example, as we go further into the subatomic state, we notice that particles of light are coming in and out of existence at an unpredictable rate, such that we cannot discern when one moment disappears into nothing or reappears into being. A similar situation occurs when we observe outer space and realize that no object in space truly occupies the position it is observed in. In outer space, the measure is “lightyears” because the realm is a place of time. Things are constantly changing, have changed, and will change. In other words, things that existed in the past may still appear to exist for the observer in the present. For example, when we look at certain stars or supernovas lightyears away, they may no longer be alive, but we can still observe their light remnants from our position.

Predictable vs Unpredictable

In a biochemical sense, we cannot predetermine whether a life-form is conceived into birth, or deceased out of being, or when the composition of one chemical occurs over another, causing a chain of reactions known as metabolic activity—the activity of living. Birth and death are only observed at the normal state of perception. At more imperceptible dimensions of reality, the being or non-being of any given event is unknown because it is unknown generally in reality—i.e., it has not yet happened, or has already happened, or it does not matter. Ontology, however, is more fundamentally an ethical kind of knowledge, which takes technical facts and uses them to draw conclusions—or rather, to make a judgment about a certain situation.

Ontological knowledge concerns the facts of ethics. An example of an ethical fact is that mammals give birth to their offspring alive. The fact about triangles is always true, but the fact about mammals is only sometimes true. However, ontology springs into action when confronted with the question: how do we confirm the relationship between technical and ethical truths?

The post-modern ontological stance argues that because ethical facts involve uncertainty, there is ‘no’ absolute truth. Arising from this foundation is a peculiar version of itself: the purely technical sciences adopt an inherent post-modern tone when they disregard ontology generally, and cling to purely “practical” knowledge. The true route of ontology looks at the uncertainty underpinning ethical truth, and makes the objective conclusion that ethics is inherently more uncertain than technical truth.

The uncertainty in ethical truth is itself a truth, one that involves more complexity. The complexity of one form of knowledge is solved with the other, and so, in the case of ethical truth, the fact might be uncertain—whether the child makes it out alive—but it is certainly true that mammals give birth to their offspring either alive or dead, i.e., sometimes alive, sometimes dead.

“The fact could ‘not’ be other than it is”

Confronting the uncertainty of “ethical” truth is the first practical step because it opens the “proper grounds” to act on or decide what to do next with the newly realized knowledge. This is what Aristotle means by “the proper object of unqualified scientific knowledge is something which cannot be other than it is.” In other words, scientific knowledge is achieved when “the fact could not be other than it is.” This is similar to what Charles Peirce says: a scientific fact is already true whether you know it or not; your knowing of it is the self-conscious confrontation of it. Hegel elaborates:

“It is this becoming of science in general or of knowledge that this phenomenology of spirit presents. Knowledge, as it is initially, or the immediate spirit, is the lack of spirit, the sensory consciousness. To become authentic knowledge, or to generate the element of science, which is the pure concept of science itself, it has to work its way through a long course. This becoming, as it presents itself in its content and in the shapes emerging in it, will not be what one initially thinks of as an introduction to science for the unscientific consciousness; it will also be quite different from the foundation of science; at all events, it will be different from the enthusiasm which, like a shot from a pistol, begins immediately with absolute knowledge, and makes short work of other standpoints by declaring them unworthy of notice.” (Phenomenology of Spirit, p. 27)

The “demonstration” is NOT merely the illustration of the fact, but rather it must have true premises prior to the conclusion; that is, the premises must be known before knowing the conclusion. The “premise” is the ‘area’ of knowledge, which is the field of facts that the individual is confronted with. The “conclusion” is the definite point of determining these facts and organizing them into a certain view. An “opinion” is a conclusion without having considered the premise thoroughly; in other words, it is unsupported by any premises. An opinion becomes an ‘argument’ when the conclusion is treated as a premise, because it can be judged, argued for, and determined to be either sound or unsound, etc.

the 2nd condition of Science “Things that cannot be otherwise”

The second condition of scientific knowledge is that we know only the “things that cannot be otherwise.” For Aristotle, science is only able to process what is possibly true. It is impossible to think of not-something because, in doing so, you have thought of it. Any negation of a thought is just another thought. Try to think of nothing. For example, it is impossible to think of not-a-cat because that triggers the thought of a cat, and perhaps even the thought of a dog, and so on.

When Aristotle asserts that to gain scientific knowledge we must have the “cause” of the fact, he is claiming that we must know the reasons why the conclusion is true, even if we are certain of its truth. It is not enough just to ‘know’ something; you have to be able to demonstrate it.

The mistake in thinking, or the moment when an ontology becomes a false one, happens when the thinker fixates on a conclusion and finds comfort in that. This is the definition of “partial” knowing. We see this in the philosophy of David Hume, with the problem of induction. Hume raises the question of why we believe that the future will resemble the past. This is the same problem with unobserved things based on previous observations, such as the “rising sun”—the fallacy that the sun will rise every day.

The application of time presents a challenge to what is considered truth. The element of time changes phenomena in the sense that, first, things may no longer be true—that is, things may no longer exist—and second, even if phenomena are eternal, the observer must consistently rediscover them.

There may be many beliefs concerning the nature of an object, but there can only be relatively few true conceptions about what it actually is.

This is why you cannot simply take certain true facts from an incomplete theory and maintain the truth of the relationship between the facts and the theory. The instance when a false ontology uses correct facts does NOT provide a true worldview. This would be doing the very same thing that made the ontology improper in the first place: “complete” facts assumed to complete a partial worldview.

Worldview

A worldview is NOT a concept or a religious belief because these are what we mean by “completed,” ready-made ideas given to the public. A worldview is a natural and organic phenomenon of consciousness, allowing one to conceive a “picture” of the world. A so-called “pseudo-worldview” or “ready-made worldview” consists of ideologies about the complexities of the world that provide simple notions to satisfy our curiosities. However, with this “cure” comes the fallacies and falsities of “deep” and genuine illusion. These kinds of “worldviews” are provided to the general public so that they do NOT have to “think” for themselves. These constructed world “views” do NOT want individuals to activate their own self-reflective thinking, so they do NOT have to “think,” or produce, but simply consume a “belief” and passively accept how things are, without questioning the model of reality.

A “true” worldview is how you actually view the world if you used your mind and natural faculties of sensation to their full potential. The latter is how you “see” the world, and the former is how you conceive it, bringing the world into being. By “true,” I mean the organic way of seeing the world. Unfortunately, that is in-and-of-itself incomplete because it is identical with the level of development at which the individual is, during their life, and to which they are confined by nature. It is the individual’s uncertainty that decides what is good and what is bad. This immediacy is what we observe as “real time”—i.e., time that is NOT determined in a fixed way, but where determination is ongoing, and you must choose what is being determined into being. In physics, the idea of “real time” manifests as motion. The notion of existence “now,” in the present, happening right in front of the observer, exhibits itself as an object maintaining its same identity, even though it occupies different areas in the length of spacetime, i.e., motion.

Study of Ontology

The study of ontology does NOT merely accept what is prevalent among cultures or epochs, but rather examines how culture reacts to what a few “world-historical individuals” agreed and disagreed about. Ontology can be considered the true science of individuality, as it reflects on those few individuals in history whose uniqueness forms the foundation of our shared knowledge. It is the study of “individuals” by individuals because their lives and rational experiences shape our worldviews, and we only read about them once they are gone. They no longer exist, and therefore they have no ongoing bias. All their biases and opinions are portrayed in their fullness, and our judgment about them does not alter their views. The person is dead; they do not care nor are they affected by our judgment, and we cannot change anything about it.

We assume that “our” worldviews are unique to ourselves, but they are, in fact, the conceptions of others who are greater than us. We can say that our entire life events are the imagination of some other being determining reality from a different period in time—conceptions that disclose our own.

We are familiar with the common saying that ‘everything has already been said’; the whole of the truth is, on some level, already present, but the facts must be connected with the whole. Everything has already been said, but not everything has been said in every way, or rather, not everything is connected to everything.

Corruption of Epistemology

In academic settings, it is often NOT recommended, or moreover ill-advised, for philosophers to inquire into the concepts of physics. Concepts such as “quantum mechanics” are supposedly reserved for physicists because they possess the technical ability necessary for their understanding. However, this is a method contemporary academia uses to disassociate critical thinkers from accessing empirical facts contested as “undoubtedly” true. If philosophers were to enter the sciences, they would quickly learn that the so-called “objective” facts about nature we assume to be undoubtedly true are NOT as objectively certain as they are made out to be.

Ontology is an activity done for its own sake. This means that an individual will gain nothing externally from doing ontology, such as receiving money from selling an object. Doing ontology is the same as living life, or experiencing life, and communicating that experience in a universal manner—that is, in the scientific form it subsumes.

Opinion vs Justified belief

The difference between opinion and justified belief is actually NOT the truth, because both share the commonality of having no truth as the basis for their claims. Instead, they use factors “other” than the truth as the basis for judgments. This means that “opinion” literally refers to a judgment (view) NOT necessarily based on truth (fact), but rather on feeling or something else. On the other hand, justified belief is based on probable truth, but it remains uncertain. The physical scientists safeguard their facts against philosophers by emphasizing “specialized knowledge.” Modern academics no longer provide a general basis before branching off into specialized sciences; the relationship has now been inverted. In Ancient times, every scientist was first and foremost a philosopher, meaning their so called ‘specialized knowledge’ was the practical application and consequence from their general (theoretical) philosophy about the world.

Nowadays, philosophy is merely a topic among topics, with subordinate importance in the hierarchy of knowledge. It is a ‘class’ that everyone makes fun of and ‘no one’ takes seriously. This reputation of philosophy is artificially produced by modern academia to prevent thinkers from formulating a proper worldview, so they can simply employ the facts and theories given to them by their teachers. And remain ignorant of the ever-lasting truth.

War of Ideology

Beyond theory, the vulgar materialist, which are the post-modern equivalent of today’s “scientist,” wants the truth of the fact to be limited to what is perceived, and NOT to what is thought of beyond perception. Human perception is easier to manipulate than logic.

The faculty of understanding itself is being contested here, because while all the factual empirical proofs about nature can be found, how those facts are used to construct an ontology—a worldview about nature—is the concern of philosophy, which science depends on.

At the base of science, there is a war of ideologies; whose “view” of nature is adopted by the general consciousness determines the actual future conditions of nature itself. Ontology is NOT just a way of ‘seeing’ (viewing) the world; it is a way of determining the world. If epistemological inquiry takes thought to be the object of thinking, it must NOT simply apply thinking to its subject matter without applying the subject matter to thinking (Hegel’s general notions of logic). To make thinking subordinate to the subject matter means to accept the subject matter in the way it is given, without questioning, and to maintain this falsity by talking about it in the way that it is “meant” to be talked about.

Contemporary Epistemologies

Contemporary epistemology does NOT want the subject-matter to be applied to thought itself, because “thought” is a free and questioning mechanism. True understanding will NOT simply restate what the subject-matter wants it to restate, but will question why it wants it to restate what it is requiring for it to restate. Thinking will wonder what the motive or intent behind the concept is. What is the intent behind the concept?

The empiricists who dominate epistemologies will argue that the concept has no motive; it is “impartial.” How can a fact about “rocks or magma” have a motive? They claim the fact “is what it is,” in other words, it cannot be attacked because it exists outside the “subject” making the truth. However, this epistemological principle is misused, causing the opposite of what it is intended to avoid. We don’t know whether the facts are true or not. The “facts” may NOT be true and may be used as true by individuals perpetuating a bias. They use this strategy to deflect the motives that the thinker himself has in using the facts for a definite purpose. In other words, the facts are always used to support or distort a particular narrative, worldview, or ontology.

In the epistemological logic, “thought” is argued to be separate from the object, and is assumed to be attributed to it from the outside. In this sense, the object portrays no concept of thought. The object is lifeless and exhibits a set of fixed peculiarities that thought observes. This is derived from a materialist ontology. The particular facts are always used to promote a general notion by wrapping them into a ready-made package capable of fitting the narrative they are pushing. The facts may not have a motive, but the scientist using those facts always does, whether for better or for worse.