Absolute Principle (Reality)

To say that the ‘objective’ of our study is to “search for the truth” is a somewhat misleading assertion because the concept of truth is far more complex than a mere proposition. The misunderstanding arises when the thinker assumes that “truth” is something that can be immediately presented upon request. When the object is pointed to and “picked out” by perception, it is called a “reality” because the phenomenon now exists for the observer to experience. Experience is both mental (nominal) and physical (phenomenal). However, what exists in reality is not necessarily identical with what we mean by the “Truth.” The capital “T” refers to an absolute principle—something that nothing else can transcend. Even though we may not have direct access to the “absolute” because it is beyond any finite conception, we must still accept its principle as universally true. For example, there must always be a principle greater than any finite set of observed conceptions, regardless of how many there are. There is always an overarching principle that encompasses any set of observable phenomena within the reference frame of an observer, even if that reference frame itself is the absolute principle.

The “absolute” is a recurring derivative, always following itself. This occurs in two ways: first, in the physical sense, where the absolute is a derivative that allows one object to be picked out as separate from and outside other objects. Second, in the purely mental sense, the absolute principle is a derivative where one reference frame always discloses and encloses a set of externally related objects. The second point is referred to as “internal relations” because the substance is always disclosed within itself—there is no truly “outside” or “other” scale independent from itself; everything is always “internal” within it. This further characterizes the absolute as a primary principle, whereas the first point describes it as a secondary quality, where the absolute contains secondary qualities that are not identical to itself as a primary principle. There is always a principle “greater” than any preconceived notion or any object picked out. There is always something “greater” or something that belongs outside itself. The “greater” always discloses something within itself, as the total number of any set of objects outside of themselves.

In geometric terms, the “greater” would be the enclosure of a figure—there is always an aspect of an object that is “concealed” behind its figure. In quantitative terms, it goes “higher” because it represents the maximum, which constantly defeats itself for a higher number of itself. The greater is the higher, and the most intense of any magnitude. In physics, this theoretical process represents a maximum intensity speed. The speed that reaches a limit is a stationary object, or in an inertial state, unmovable. In substance, this is called “light.”

Speed of Light (limit)

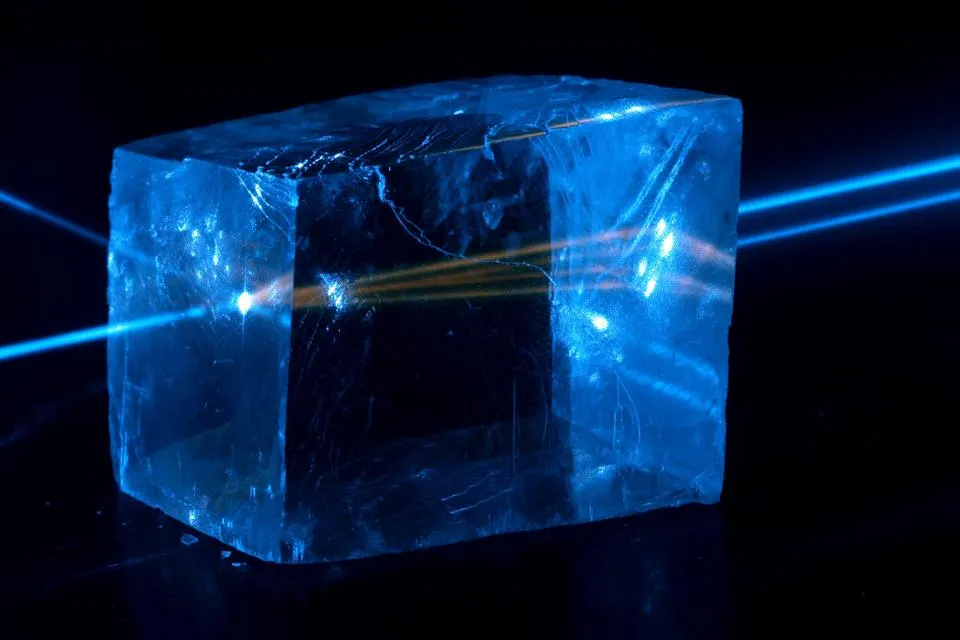

The speed of light is considered the limit because the reflection from any object, at the lowest possible density, embodies the lightest conceivable essence of matter—light, in this sense, being the fastest substance in time, is also the lightest in composition. As we approach this limit, not only is the position of the substance further along in space, but its future iterations—its “versions” in time—also occur after and “later” than the present moment.

The essence of matter extends beyond any particular object, reaching out into the space “around” it and beyond. This essence always stretches further than any step taken in motion, regardless of direction. In other words, when an object moves in a given direction, it exhibits a reflection of itself in the form of light, which stretches outward. The light, as part of the spectrum, represents the peak of that wavelength, the furthest reach of its motion. At this point, motion effectively stops—an object is abstracted, and we may mistakenly call it “theoretical.”

Light, however, is a concept rather than a strictly “real” limit. It represents the theoretical limit of matter in motion, the fastest rate achievable. At this speed, whether an object is from the ‘past’ or the future ceases to matter because both versions of the continuum—past and future—become unified into a single, abstract moment. The result is a set of parallel moments, existing simultaneously, frozen in an inertial position within spacetime. These moments are no longer distinct, as they collapse into one unified experience of time and space.

Reality vs Truth

Reality and truth are interestingly distinct concepts in philosophy because they do not necessarily presuppose each other. Something can be “real,” but that does not mean it is the “truth.” The concept of “truth” presupposes an ethical value that reality is deficient of—an ideal that is not fully realized. Reality presents an illusory aspect to the observer because “real” things may appear in one way, yet they can fundamentally be different from how they present themselves in perception.

It is true in the sense that it exists, but its existence does not encompass truth in its complete form. The distinction here is subtle but important. Existence, in a basic sense, means that something is present or has being—it is real. However, the concept of “truth” goes beyond mere existence. Truth involves an ideal or a principle that can encapsulate not just the fact of existence but also the full nature or purpose of that existence, often with ethical, logical, or metaphysical dimensions.

In other words, something that exists may be real in the sense that it has a place in the world or in our experience, but that reality might not fully reveal the deeper, complete truth of its nature or purpose. Existence is partial, while truth encompasses the whole, including all aspects of an object, its relations, its implications, and its context. Thus, while an object may exist and be “real,” its truth is something that may remain elusive, partial, or only revealed through deeper understanding.

When we point towards an object and observe what appears to be a definite and specific “thing,” the reality is that the object is “not” merely what it appears to be. The perception of the object is a mere “abstraction,” because the “object” is only a limited view of one moment within a longer and enduring process. This idea is demonstrated by the physical nature of light at the “fastest” speed. Light becomes a wavelength whose particle states—the beginning point, the endpoint, and the source—are unknown.

The speed of light is the form through which objects maintain a continuous and intact physical nature. We can say that every infinite set of particles composing an object or person, at the microscopic level, is moving at the speed of light. These particles somehow “form” by stopping at the edge within the finite circumference of the object, disclosing its appearance.

Nominal – Future Moment

The task of science is to use perception to go beyond mere “perception” and enter the domain of the abstract, or, in other words, the realm of the “nominal”—which refers to the stated and expressed value, but not necessarily the “real” value. The so-called “expressed” value is another term for the “potential” value of a phenomenon, i.e., what it “ought” to become, or what it will grow into being. This value is “abstract” because it is not yet realized, but only exists as a “potential” moment in time, meaning that a moment will happen in the future.

A future moment, or a moment in the future, is an abstract moment that concretely exists, meaning that the current present physical situation of time cannot do without it, but must depend on it for its existence. Abstract substance, or the nominal, is distinct from the phenomenal, or what is immediately present before the observer, but it is still known to exist. In other words, it cannot be directly perceived, but we know its existence indirectly through the direct observations of other things that depend on it.

Ideality in Reality

What the “real value” is, as opposed to the “nominal value,” is not entirely clear. The distinction between the nominal and the phenomenal presents the paradox of “reality” opposed to “ideality.” The notion of ideality challenges reality because, while we know that there is a “reality,” we do not fully understand what this reality is—this is a deeper, and still unknown, question. The fact that something exists does not tell us what it is.

The current fact of something’s existence does not inform us of the potential or future outcomes that may occur to it. This notion is central to the concept of ideality because it presents itself as an unknown element of reality. The former (reality) is known, while the latter (ideality) is only known indirectly, through the invariable need for the former.

What is the fundamental nature of reality? This question can be answered by asking another: What does it mean for reality to be constituted by something more fundamental than itself? By “fundamental,” we mean something that comes “prior” to other aspects in terms of its necessity for existence. If one variable is “prior,” it does not depend on the “latter” (coming after it) for its own existence—it can exist before the latter. If the fundamental nature of reality is not what is observed, then what is the phenomenon of experience? The idea that an object (thought) also verifies as experience is the central claim of the phenomenal.

Phenomenal

The phenomenal realm is the state, the way, or the condition of phenomena in order for them to exist in the objective way that they do, allowing all modes of sensation to pick them out as specific and finite “things.” Although observers may constitute different avenues of experience, they generally share the same system of experience—i.e., the world—and this includes the most fundamental aspect of it: the “Reason” it exhibits. The world and its most essential aspect, the experience of it, unify to denote a phenomenon that is defined as an experience in every possible way, experienced in every way possible. The phenomenal cannot leave the most essential form of experience (Reason), even more fundamental than sensation. Thought is the first experience, before it becomes realized through sensation as real moments for an observer.

The Paradox of Being

The paradox of Being lies in the form of experience: the phenomenon exhibits itself directly to sensation, but is hidden implicitly, indirectly, from thought, which holds its essential cause—what it will become later, after. These sequences of the unfolding moment into experience are known as phenomena, which present themselves directly through the observer as an object “outside” for them to experience. However, the experience itself raises questions because it presents varying degrees of reality. In other words, reality itself exhibits varying degrees of existence in actuality. Reality is not the existence of one thing, nor does it exist in just one way.

Reason knows it to be true, but not by apprehension through sensation. Thought can only confirm reason with the truth-value of its claim by rendering it as one of many possibilities that take on a particular form. Each form is not identical to the other, but the other is none of each form. Therefore, the same gradient of reality presents varying degrees of depth in experience. The experience itself has varying degrees of depth, and this depth corresponds to the varying depth of the object itself that is experienced. Thus, the mode of attaining experience (the medium) and the experience itself (the object undergoing movement within that medium) both have varying degrees of depth in their connection with each other, forming a continuum of reality.

Reality is a dimensional depth of experience. The level at which experience reaches a “limit” in the dimension of reality will vary depending on the development of the observer or modes of sensation through which the experience enters. It also depends on the object’s movement within the very same medium that produces it into being in the first place.

Negative

The “object” we observe is never “not itself.” It is always “itself” and, therefore, an “other” to something else, which is always “itself” an other to yet another “self” distinct from itself.

This means that the object is always, first and foremost, itself. However, it begins from the “negative” of itself — from what it is not — and emerges into its own identity.

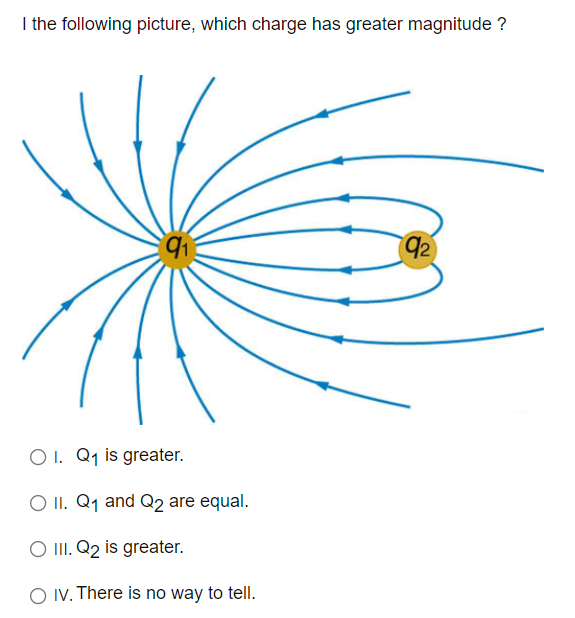

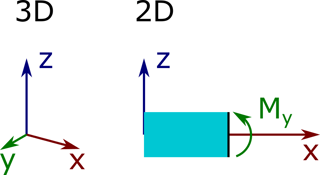

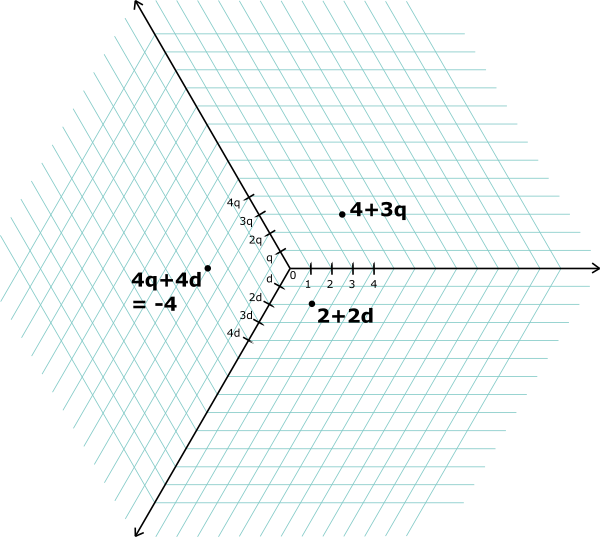

The minus sign (-) as seen in 2D is different from its meaning in 3D. In two dimensions, the negative sign appears as a straight line, but from a three-dimensional perspective, it extends toward the observer as a vacuum or a wormhole, symbolizing entry or disclosure. The minus sign represents a negation within a positive process. In contrast, the plus sign (+) is depicted as an intersecting cross, forming a grid with x and y axes.

What do we mean by beginning the argument from the negative? In logic, initiating an argument with a negative is inherently contradictory, because asserting the negative presupposes its opposite — the positive. The positive, in this case, is the initial condition, as any beginning is inherently a “step taken” toward the being of a thing, not its opposite, its non-being or non-existence. Therefore, the “negative” represents the “other” or the non-being of an identity, while the positive represents the identity of its being.

Positive

The opposite being of one thing is simply the proposed being of another thing.

According to informal logic, we always begin with a negative because the positive is already presupposed; it is the element that is most abundant. The positive is inherently self-evident because anything that “is” — “either, or” — is at least present by not being a specific thing at all. Therefore, the first positive step is actually a “negation” or a negative, emerging from the predisposed substratum. The negation is the act of “taking away,” subtracting from something.

The positive lacks any specific identity because it is convoluted by all the determinations required for something to exist as a positive. The negation, therefore, limits the positive — which is a convulsion of all actions — into a specific, finite instance, making it clear.

The positive sign (+), when intersected by the minus sign (-), forms the three-dimensional grid of space. In other words, space is a fundamental conception of the mind.

The identity that lacks an identity is always a particular identity, as opposed to having no specific identity at all. To lack identity entirely is to be general, not particular.

Any beginning of an assertion is initially a “positive” in logic, including the first assertion, which is a negative. The negative is fundamentally a positive because the very first attempt to do anything — whether it is the addition to an action (i.e., continuing the same action) or the subtraction from an action (i.e., changing the action) — both exist as positive(s). Yet, they are negative because it is not immediately clear how they exist. How something exists, as opposed to the fact that it exists, is always an opposition between something that is already an “other” of itself.

Object

The term “object” is simply used to refer to “something” that exists in a specific and unique way. However, the word (or term) alone does not explain the “nature” that makes a particular thing the kind of thing it is.

The term “object” is the general concept for something particular.

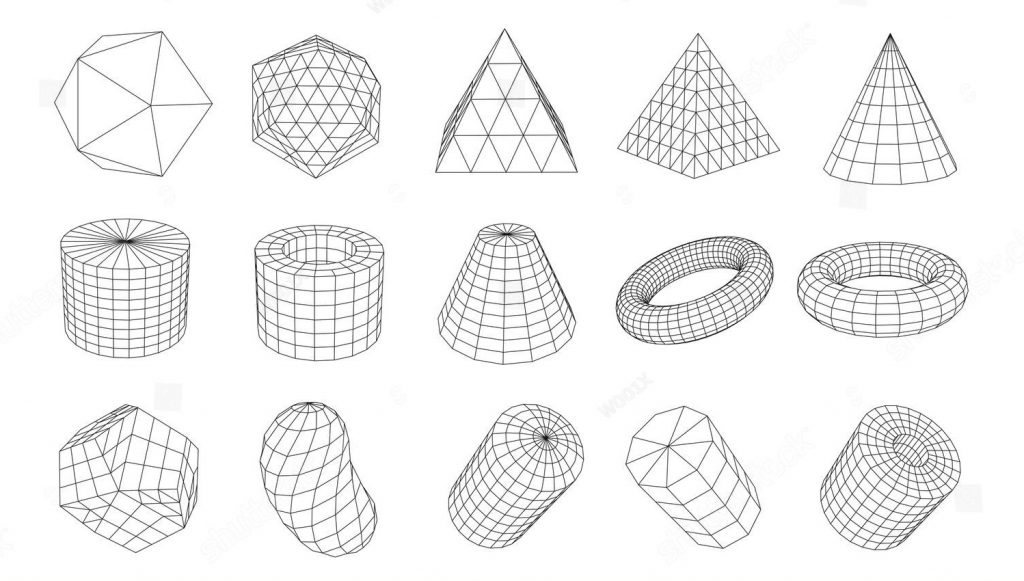

The same grid forms into different modifications of itself; the abstraction of these modifications into each moment or instance is what we call an object.

The “objects” we observe around us at any given moment are “dimensions” in spacetime because they have a greater magnitude of experience beyond their immediate sense perception. Ordinary perception views a limited scope of the object. We see things as “solid” and dimensionally constrained by the resolution of their qualities, but objects are much more complex and deeper than what we observe — which is often a vague, homogeneous grain expressing a particular quality. In order for an object to bear quality, it must first be devoid of quality.

Quality

The object has a “specification” of a vague kind of form. The orientation of this form on a plane consists of a corresponding set of related orientations of forms that are adjacent in nature but share the same area within the plane. This process, on a plane, of disclosing a set of differing orientations of the same form is what we define as quality.

The mind processes these different modifications on the plane as a homogeneous whole, expressing a unique and particular form that performs a function. We are able to recognize its purpose due to our experience within a limited and naturally confined point of view. However, if you look closely at any given object, what we always observe, when we enhance the resolution of its grain, is that one object is always made up of many smaller, akin types of related objects, each cooperating together to form the generality they belong to. One object is always the sum of other related objects.

Quality is the action that utilizes all the internal relations, shaping an object into an aspect of experience for the observer. In other words, the observer can recognize quality because it performs a function for him, providing value to him.

Seeing the Figure as a 2D Object.

Possibilities

The “mental resolution” is the capacity of the observer’s mind to process an indefinite set of possibilities into a definite and real moment. A “real” moment is a point-of-view from the observer that identifies a set of unique objects. However, these objects are limited to an indefinite set of different ways in which they may “be”, or may interact with each other.

The number of possible ways objects may interact with each other on a plane, as disclosed by the observer’s conception, is called the “possibilities” of events. The possibilities of events are not limited to the number of ways objects may or may-not interact with each other; they also include the number of ways an object is internally related to a set of other objects that compose it as an integrated component. A set of “possibilities” always belongs as a group within one unique kind of “certainty.”

Minute

We define a set of objects as “possibilities” within the realm of temporal time, and not just extended space. For example, one “macroscopic” object is made up of many “microscopic” components. This fact implies that there is a spatial extension concealed within the circumference of the object’s figure, which hosts an infinite number of more “minute” durations of time.

The word “minute” seems to have two unrelated, but correlated, meanings:

- The first meaning of “minute” refers to a “short” interval of time.

- The second meaning refers to something extremely small.

How is a “short period of time” related to a “small area of space”? These different meanings in the definition cover both the time and space requirements of what constitutes a phenomenon.

Every object is both simultaneously in space and instantaneously in time. A “minute” in the temporal sense is “a period of time equal to sixty seconds, or a sixtieth of an hour” (search “minute definition”). As an element of space, it measures a certain duration (it covers an area) wherein a set of events are disclosed to occur and concur simultaneously. These events are disclosed as self-identities that are separate from each other by space. In space, this is equivalent to objects instantaneously occurring in relation to each other. That is, one does not have to cease in order for the other to persist. Objects can simultaneously exist in space while enduring different experiences of time.

In the spatial sense, the term “minute” refers to an infinitesimally small area of space wherein a set of events may or may-not occur. The negative of occurring, “not,” is itself the “space” — or rather the interval, or “pause” in time — where existence is opposite to itself, i.e., non-being or nothing.

The spatial and temporal definitions of the concept “minute,” when considered together, demonstrate that within a short duration of time, like a minute, events at the smallest scale come — in and out — of being at an extremely fast rate, happening faster than the macroscopic objects they compose.

The smaller the area of space, the shorter its duration in time. In this way, if the smallest areas correspond to the fastest rate at which events occur, and therefore the shortest time it takes for something to exist, technically, the smallest areas can host the maximum number of events. However, this is counterintuitive, because what we observe is the opposite: it seems that the largest areas of space contain the greatest number of objects. This occurs because, in larger areas, the slowest rate of events takes place, and therefore the longest durations are observed. The longer the time, the more events are able to happen. Why is it that opposite and inverse magnitudes of the universe bear the same results, yet with opposite presuppositions?

This concept is detailed more precisely by scientific notions such as “zero-point energy” and the Schwarzschild radius, which are discussed in greater detail later in other sections.

Permanence “eternity”

The opposite of “minute” is permanence, defined by eternity or “forever.” This notion follows a principle: as objects increase in size, they seemingly decrease in number, and the length of their duration increases in time. Correspondingly, events constituting objects at the largest scale occur at the slowest rate of time, and they take the longest time possible to develop. However, the relation between these two inverse magnitudes of spacetime is the missing factor.

The relation between these two extremes of spacetime is the observer. As an object moves further away from the observer, its size becomes less relevant, and it could simultaneously be both large and small. Its measurement becomes abstract. The object appears large when it is furthest from the observer and small when it is closest to them.

Only an abstract entity can be permanent and last for eternity. All physical objects we observe are generated and then decay, while abstract principles are permanent and unchanging. Like Plato’s Forms, they are immutable, innumerable, and eternal. However, even this is an assumption. The ancients used to say that the “heavenly bodies” are eternal, yet modern science estimates the lifespan of planets and stars to extend millions or even billions of years—well beyond the lifetime of any living being capable of making such an estimate. It is quite convenient that we assign grandiose lifetimes to celestial bodies that we have no direct means of observing or proving.

There are events in space that we observe, such as stars in “collapsed states” (“Dwarf stars”) or black holes, and we describe these as moments of decay or generation. However, even these are abstractions. We have no true way of actually witnessing their processes unfold in the same way we observe objects we have direct experience with. For example, if we leave an apple out for a few weeks, we can clearly observe its decay. It seems that decay and generation, like size and distance, are related to the proximity of the observer.

This above claim is not to suggest that the universe is static; on the contrary, the universe is dynamic, but not in the way we observe the dynamics of objects in direct proximity to the observer. The dynamics of the universe are more abstract, meaning they are related to the rational mind conceiving the world. This can be reiterated by the observer principle, which essentially constitutes the foundations of cosmology.

Infinitesimal

Any given single object is large or small relative to the observer who is most spatially proximate to it. The size of the object is determined by its circumference, which discloses an infinite inwardly extended dimension. As objects move further away into that dimension, and further away from the observer, they appear smaller to him. The “minute” objects of the microscopic scale are not inherently smaller; they appear the smallest because they are furthest from an observer situated close to an object on the macroscopic scale, which appears relatively larger.

If each object picked out by perception is observed closely, or in other words, more clearly — i.e., by enhancing the resolution — it is not improving the sense organ’s ability to carry out its function, but rather by conceiving more possibilities disclosed within the same dimension. The function of the sense organ is inherently limited because it is designed to pick out a vague conception of a single particular quality in the first place. The notion of “resolution” refers to the clarity or detail with which something is perceived, observed, or measured. resolution refers to the smallest distinguishable difference or the finest detail that can be detected by an instrument or measurement system. For example, a microscope with higher resolution can distinguish between smaller objects, revealing finer structures.

One object is made up of many smaller possible conceptions of the same object. The notion of infinitesimals combines complex fractal symmetry with durations of time and space. As we look deeper into the physical makeup of the object, we notice that within the outline of its circumference, it conceals an inwardly infinite amnion of super-symmetrical fractals.

Problems with the “Truth”

The phenomena being conceived, when pointed to and asked, “What is its nature?” as if the nature of the object is “presentable upon request” in the sense that: a) the object can be located and then pointed to by perception. When asked, “What is the truth?” people expect a straightforward answer. Specific things are forms of truth, but the “universality problem” concerns how one thing in general can be many things in particular. Truth, in this sense, is the ultimate nature of things and, therefore, the totality of the way something is specified. This is what logic is, and it constitutes the same question as to what truth is.

In this way, truth is not a thing in the sense that we point to an object and say, “It is that one thing.” Yet, we cannot help but think that there is something certainly true. We look towards objects and take those as our objects of truth, but that is only the search for a certain truth. The fact that truth is certain does not mean it is limited to a single thing, even though that is how we commonly come to know things.

Truth with a capital “T”

According to Aristotle, the subject-matter of logic is simply the “Truth,” which, in that tradition, is referred to with a capital letter. This is not just a translation error, but rather reflects their view of Truth as something universal and infinite, with each “object” beginning with the Truth. The Truth is not merely a factually accurate claim; it is also the natural and real essence of the object, which is a particular expression of it. This means that knowledge does not “search” for the truth, like a hound hunting for its prey, but rather, knowledge is one with the Truth—I.e., they are the same. Even if someone knows instances of truth that occupy their entire day, but lacks a true belief or a true “worldview,” they are someone who knows the truth in the wrong way. This is what truth-is-not. Knowing instances of “truth” is not the same as knowing the Truth.

The capital “T” abbreviates the normative logical element indicating a “universal,” which is “first” or a primary principle. Something is “first” so that it can fully encompass all following or preceding variables within the series. The qualitative aspect of a “universal” in philosophy is that there is something higher in the idea of Truth—something better and beyond ordinary reality. To put this claim in more concrete terms, consider the fact that throughout all known history, man has experimented with altered states of consciousness in order to access higher moments of awareness, even at the expense of his overall mental well-being. He either remains sober throughout his life and experiences short, scattered, and ordinary moments that he may not even understand or be fully aware of, or he sacrifices his future mental fitness for short-term periods of enlightenment during a high from altered states of consciousness. Man sacrifices his future mind for short-term enlightenment, or he sacrifices short-term enlightenment for a steady, gradual progression toward enlightenment. Obviously, the latter might be more sustainable than the former, but most often, people cannot achieve the former and resort to the latter, even at the expense of attaining both.

This notion of the “higher” springs from the inherent dissatisfaction that man may experience with his ordinary mental capacity. It seems that, after a time beyond childhood, man becomes accustomed to his ordinary way of seeing the world; his consciousness becomes stale, and he gets used to the way he sees the world every day. In this sense, throughout history and continuing to this day, man has searched for substances that cause altered states of consciousness, whether for the better or worse. His unavoidable need to change his habitual way of perceiving the world often overrides rational considerations, leading him to take substances even when they are harmful. Man has an urge to alter his consciousness, even at the cost of his health.

Why is man dissatisfied with the way his mind normally perceives the world? The answer is that he knows he is not seeing the full picture. Whether consciously or unconsciously, he understands that his consciousness of the world is limited to what is necessary for his survival. Yet, he desires more—conceptions of the world, a higher resolution of total reality. A reality is distinguished from a Truth on the basis that the former never fully expresses the condition under investigation, whereas the latter must always include what the condition is limited to: what it is-not, the other, the more or less, the moreover, and beyond the immediate thing at hand.

Speculative Language

The process of “knowledge” does not attain the ‘object of truth’ from the outside during a moment when it lacked it. The use of a capital letter, even when not at the beginning of a sentence, goes beyond grammar and into the domain of speculative thinking.

Logic is impeded by language. The basic logical step distinguishes two categories from each other: the universal from the particular — these concepts are explored in other sections.

We cannot simply present an “object” to the reader and claim that it is the “truth,” because the view of a single object must exclude other things in order to be distinguished as an individual piece in the first place.

By the affirmative definition of an object, as an individual, we impose a limitation on truth generally. A particular instance of truth, which is true by being a part of the whole, is simultaneously not true by being a narrow version of it. Truth is certain not in the sense that one can know true instances and then be said to know the Truth.

Truth is an ‘Ideal’ – ‘God is that which is Not that’

In classical Christian and Islamic doctrines, it is said, “Whatever you can think of, God is NOT that.” Or, in Anselm’s case, the concept of God begins as that than which nothing greater can be conceived. To think of such a being as existing only in thought and not also in reality involves a contradiction, since a being that lacks real existence is not a being than which none greater can be conceived. God is always beyond the explanation attributed to it. The idea that God is a real entity independent of the mere speculative concept used to try to understand it is ancient, dating back to the prehistoric ancestors of humankind. A different species of human being led to the “evolutionary leap” that brought us to our modern selves today.

Truth is an ideal, and is therefore also ethical. Knowing what is right and wrong is identical to knowing what is Truth or not. For example, the moral virtues correlate with the intellectual virtues: someone who is scared will be irrational, while a coward will act erratically; on the other hand, courage is aligned with wisdom, as the courageous individual is more focused and can act according to the situation.

The difference between virtue and vice — courage versus cowardice — lies in the individual’s reaction to a dangerous situation. The real is what happens, while the ideal, which is how the term “Truth” is defined, is the quality that makes the real lacking that element beyond itself.

Historically, this idea has been qualified by the notion of God as the highest quality, under which everyone is equal, implying that everything is equally inferior under God. However, the elusive idea of God means that everything is equally inferior, or that inferiority is a feature of everything — in other words, everything is corruptible, except the undefined idea known as “God.”

The idea of God has brought utility to the “ideal” in thought, but in an inverse way, by showing the highest value. A recognition of the opposite value — death and corruption, both physically and morally — contrasts with purity and eternity. These are the definitions of essence.

How to ‘know’ the Truth

The problem with asking the question “What is true?” presupposes its answer, and at the same time, presupposes the opposite of that answer.

The natural follow-up question, “How do you know if something is true?” is really another way of asking, “How can you properly explain something?” Implied in both of these questions is the presupposition that there must be something actually existing, and at least true in that sense, and that there is the possibility of knowing it in a different way than it already exists — the potential for it to grow or become something else.

The ontological question is not whether there is truth or not, because the answer is already implied in the question: there is obviously both “true” and its negation, “not true,” both of which exist. However, they do not exist in the same way, as they are not the same kind of existence(s).

The real question is how to distinguish between what is true and what is not true. This is an ethical question, which brings its own difficulty: presupposing truth in what is not true. That is, something not true is still true in being the opposite of truth. This brings us back to the question: what makes something true, as opposed to something untrue?

The ‘Object’ of Truth

The truth is not presented as an object.

When we say “the object of truth,” we do not mean an object for a faculty of knowledge. Rather, the knowledge faculty itself is taken as the object for its own study, along with all the conceptions that accompany it. Among these conceptions are also objects. The reason for this predicate is an ontological move, where the notion of thought is made the most fundamental, and everything after that — including physical objects — follows as determined aspects of it.

Truth is not located.

Truth is not located like an object in the environment that satisfies the feeling of having found it. When we say that “Truth” is the object of our search, this creates the need for something ultimate, without a clear idea of what that is. As a result, ordinary understanding simply associates the lowest common denominator of truth — what is immediately confronted — and treats that as the ultimate truth. Humans in their search for the truth share a close proximity to primates in how they observe the world around them. This is where evolutionary theory may find some success—not in explaining the development of life, as it falls short in doing so, but rather in showing similarities between living species in the present. As much as humans are intellectually superior to primates, they still primarily share the same nature in how they experience the world.

Monkeys view the world as a set of objects they can pick up and examine, such as food, to determine whether it is fit for eating or not. Humans, too, have this innate inclination to view the truth as an object they can “pick up” and investigate through their senses. However, the key difference between humans and other primates is that the human mind can perceive the abstract as an object independent of the physical things they perceive. In fact, humans often presuppose that the abstract substance—something they cannot directly perceive—is more fundamental than the tangible objects they can observe. This capacity is the unique mark of humanity and makes the search for truth a spiritual endeavour, rather than simply a materialistic one.

Archê

The pre-Socratic philosophers, like Thales, for example, took the objects presented to their senses as ultimate causes for everything. However, even then, they identified something in those objects that was ultimate, abstract and essential. For Thales, the “water” he proposed as the primary substance represented the essence of liquidity, which could be derived from any object. Liquidity, heat (energy), solidity, etc.—these qualities are abstract because, although they are experienced indirectly through objects, they are essences that constitute the objects that we cannot directly observe. For example, we cannot observe liquidity alone, isolated from hardness, as its own object. Instead, these qualities always come together as a bundle, forming specific objects.

The flaw in the pre-socratic thinking was that they took a single ultimate feature as the first cause of all substances in the world. In contrast, Plato introduced the concept of the Forms, which are innumerable and infinite in their combinations. For Plato, the ultimate substance is not a particular structure but rather the power to generate infinite possibilities of combinations and structures. In other words, it is not a specific structure that is ultimate, but the capacity to formulate structures that is. The flaw lies more in categorization than in logic. For example, they took fire as the source of all life, and water as the source of all objects. This is true in the sense of pointing to something essential, but it is untrue because it is a limited abstraction of the world, taken as constituting the whole. They had to take a single substance as constituting the whole if they were to properly describe essence.

Thought

Aristotle took this infinite substance to be pure activity, associating it with an abstract quality we today call thought. However, the ancient Greeks did not view “thought” as something personal and subjective, as we do today. Instead, they saw thought as something universal and organic in nature—something we access, rather than possess.

Thought is the activity of Truth.

The forms cannot be substance without acting. The motion of going up brings with it an infinity of qualities that bring it into the moment. My hand going up, which is a combination of flesh, bone, and cells—formulated by chemical compounds and molecules, all operating within the general laws of nature and spacetime—presupposes all these factors in the gesture of moving one’s hand up.

In Ancient Greek philosophy, the concept of “thought” (or nous) was often treated as a fundamental, universal, and rational principle of the cosmos. However, it is distinct from the modern, personal notion of “thought” as a subjective, mental activity. The Greek understanding of thought was deeply interconnected with ideas of logos and nous (active intellect), which were used to explain both the order of the universe and the nature of human understanding.

The ancient Greek idea of “thought” was not merely a subjective mental process but an active, universal principle that connected the human mind to the rational order of the universe. Thought (nous) was the faculty through which humans could understand the truth of things, apprehending the essential, timeless principles of reality. It was seen as a universal and divine force that humans could access, not possess, and was intimately connected with the idea of a cosmos governed by reason,

1. Nous (νοῦς) – “Mind” or “Intellect”

In its most basic sense, nous referred to the rational, intellectual principle that governs understanding and knowledge. It was often contrasted with doxa (opinion) and pathos (emotion), representing a higher, more objective form of knowing.

For Plato and Aristotle, nous was both the capacity for understanding and the object of understanding itself, or the divine intellect. It was not merely a human cognitive function but a universal force that shapes the reality of the cosmos. Nous allows one to grasp the underlying order or truth of things, beyond appearances or sensory data.

- Plato’s View: In Plato’s philosophy, nous was often linked with the Forms (or Ideas)—the eternal, unchanging archetypes of all things that exist in the material world. For Plato, thought was not merely a subjective experience but the means by which one apprehended these higher, timeless truths through rational contemplation. The philosopher, in this sense, used nous to access the higher reality beyond the physical world.

- Aristotle’s View: For Aristotle, nous was both the intellectual power and the highest form of activity in the human soul. It was responsible for apprehending the first principles of knowledge, and in his cosmology, the active intellect (or nous poietikos) was responsible for organizing the potentialities of the world into actualized form. The nous in Aristotle’s view was the principle that allows one to understand and bring order to the natural world.

2. Logos (λόγος) – “Reason” or “Discourse”

Closely related to nous is the concept of logos, which refers to reason, discourse, or the principle of rational order. Logos is seen as the ordering principle of the universe that could be grasped by human intellect. In Stoic philosophy, for instance, logos was considered the divine rational principle that pervaded all of nature. It was an underlying order that made sense of both the physical and moral universe.

In ancient Greek philosophy, thought was often seen as an activity of the mind that was connected to the larger rational order of the universe. It was not seen as personal, subjective, or introspective in the way modern conceptions of thinking are. Instead, thought was something that accessed objective truths or universal principles, akin to discovering the eternal laws of nature or the divine order through reason. For Plato and Aristotle, logos was also closely tied to dialectic—the method of logical reasoning that leads to knowledge of the truth. Logos allows one to formulate thoughts and arguments that lead to understanding, and, like nous, it was not a personal or subjective experience, but rather a universal and rational force.

Thinking is Acting

Thought is identical with action, and this is why it is the activity of truth. The modern assumption is that thought is separate from the object itself i.e., the former must observe the latter from the outside. The ancients, like the Greeks, always maintained that they are the same continuity—just different expressions of the same substance, which is fundamentally defined as Reason, and subsequently as the ‘object’ of Reason.

- Thinking as Participation in the Divine Intellect: According to Plato, the act of thinking is not just an individual process but a participation in the divine nous, the universal mind that governs both the cosmos and human understanding. To think is to be in harmony with the rational structure of the universe.

- Thought and Action: In Aristotle’s system, thought is linked to action. The act of thinking is not separated from the activity of the world; rather, the intellect or nous is what allows one to understand and direct actions in the world. In this sense, “thinking” for the ancient Greeks had a dynamic, participatory nature. The mind is not a passive observer but an active participant in understanding and ordering reality.

The idea that thought and action are simultaneous instances in the universe stems from the belief that reason is not a feature of the human mind alone, but that the human mind participates in a universal concept known as Reason. This is the main difference between the ancient and modern conceptions of reason. While the ancients saw themselves as part of a universal mind, an expression of that mind, we today view reason as an aspect of our individual minds, with our minds disconnected from nature. Reason, at a microscopic level, instantaneously generates ideas into being, and we possess those ideas in the form of mental images, intuitions, etc. However, our conceptions of these ideas arise after the fact of their generation. Just as our eyes capture the image of an already existing object in nature, our minds conceive an already generated idea into being. These ideas are simultaneously actions in nature, meaning they are preconditions for later events in time and, perhaps, objects in space.

True Metaphysics

Metaphysics is similar to all subjects because it forms the foundation of every topic; thus, every topic is connected to metaphysics in some way. However, it is also unique because it is not specifically about any one topic and does not have a specialization like other fields. Its only true subject matter is reason, which is itself a capacity used by all sciences. For example, the legal system is scientific because it depends on proof as the basis for knowledge. Metaphysics is scientifically similar in that you can know something to be true through experience.

The difference between metaphysics and all the other sciences is that experience is fundamentally mentally true before it is physically true. Science, devoid of metaphysics—or, equivalently, science with the wrong metaphysics—points to an object as the truth for experience, rather than recognizing that the true scientific aspect is to ignite that same mental experience in the mind of another person.

What distinguishes metaphysics from everything else is that its proof is not merely words or symbols of mathematics used to show an aspect of reality. It also involves the phenomenological element of transferring the abstract idea as a mental experience from one mind to another, through language, imagery, and perhaps even mind-altering substances, as means of transmission.

Justify

How do we justify actions or ideas? In the academic or legal domain, knowing something is not enough to prove it. In order to prove an idea, you have to “show” or demonstrate what you know. However, the act of proving something by revealing it is a form of truth that can be communicated to others. In other words, the demonstration of an argument is only a relevant form of truth when you need to communicate it to someone other than yourself. Yet, we are still left with the more fundamental question: how do you prove something to yourself?

You can prove something to yourself by demonstrating it—by revealing all its variables and outlining their relations. But the question remains: why do you need to prove something to yourself if you already know it? The next question becomes: how do you truly know that you “know” the subject under investigation? The answer is that knowing is fundamentally self-evident at the personal level.

What is “known” alone constitutes a justification. Knowing is the proof for existence, because to know something means that the thing has justified itself, either indirectly through another, or directly through itself. It must first exist in order to be known, yet it cannot exist if it is not already known to exist.

To know something is simply the other side of something that has justified itself, and therefore there is no knowledge without the action upon which the truth is based. The individual must not only know information and facts about the world but must also act in a way that encapsulates their knowledge as evidence of knowing.

We find this validity even today in the legal system. The claim “Innocent until proven guilty” in the legal framework presupposes the adversarial standard of truth. That is, truth is not merely what is known, but rather what can be proven. What can be justified constitutes justice, regardless of whether it actually happened or not. For example, whether you committed the murder or not does not stand alone; there must be proof to show the commission of the murder. The actual event must conform to its proof in order for it to be considered real in the court of law.

In other words, not only must the facts demonstrate the hypothesis about what may have taken place, but the valid explanation must also show the intention or thoughts behind the actions that have unfolded during any number of events that result in some conclusion. Descriptive analysis alone shows the actus reus, while the normative side shows the mens rea. To be guilty of a criminal offense, a person must have committed an illegal act (actus reus) and had the required “state of mind” (mens rea) for the criminal offense. This is a standard for all forms of justification, including scientific as well.

Action is Proof

In all specific domains, action is taken as the evidence of theory. Someone may know “facts” about the world, or possess the skill of complex abstract thinking, such as in Mathematics, but all that means nothing if they do not act “well” or have a “life worth living” (Ancient Greek: Eudaimonia). A worthy life is not subjective; here, we are assuming an “objective” standard for what makes life worthy.

For instance, we might say that a virtuous homeless man is better than a corrupt rich man. However, just because both of these examples represent extremes of an unworthy life does not mean that there are no habits or ways of living that, if followed, would lead to a “good life.” Acting well, like knowing the truth, is not about reading a manual and following it. Rather, it is about the self-honesty of the individual in how they deal with their weaknesses, problems, and struggles—how they overcome them and find their true, destined purpose. In other words, it is about discovering what they ‘ought’ to be doing. Wasting time is one of the greatest sins. Wasting time in and of itself is a sin; however, it can be considered a virtue if it is instrumental to productivity.

A person who is “bad” also knows the truth, as they still perceive the same objective reality as everyone else. However, they willfully engage with the bad aspects of that reality, which, though real, cannot be called “Truth” because to be ‘true’ necessarily includes the ethical principle, i.e., the proper relations that originally necessitated it. In this sense, the full truth involves the ideal that the real falls short of.

Ethical conduct, in the general sense, is the behavior of truth as the conception or idea behind an act. The intention behind the action is the first step.

The ‘Good’

Aristotle associates “the Truth” with “the Good” because he famously claims in the first sentence of the Nicomachean Ethics:

“Every art and every inquiry, and similarly every action and pursuit, is thought to aim at some good; and for this reason, the good has rightly been declared to be that at which all things aim. But a certain difference is found among ends; some are activities, others are products apart from the activities that produce them.”

Aristotle distinguishes between activities that give rise to products and products that are produced by activities. The difference is that the activity aims at producing some good, while the product is the good produced by that aim. This is akin to the difference between instrumental activities that help achieve an end and an activity that is an end in itself, done for its own sake. The activity is performed for its own sake and produces a product that has a function beyond itself, aiding in the achievement of some other end.

The Good is the truth because it is the “end” of a thing. The “end” does not merely mean the result or the product, nor does it refer to the final moment in a duration when something ceases to be. In the philosophical sense, the “end” is the reason something is done and the ultimate purpose it aims to actualize. The Good is, therefore, the end at which an activity aims. The Good is the “measure” of things. For example, robbers might say “you got the goods” to suggest that, regardless of the means, there is something “good” acquired—that they are after some “good,” even though what they are after may not be good at all.

The ‘Bad’

The opposite view is that the good is not merely what is gained but also the way something is done. This means that even if the result is bad or something is done in a bad way, there is still the idea or conception behind it that was fundamentally aimed at some good. This also implies that the conception of something—the desire or idea for something to be done—is good because it is the necessary precondition for anything to be done. This does not mean that bad things are inherently good, nor does it mean that merely intending to do something good, without actually doing it, is good. What it means is that the initiation of any action is the first good aim.

Even the result of something bad has the good of unveiling the bad. The practical maxim is that the first step in doing something is actually doing it. Even if it is done poorly, at least it is done and can be improved—or, alternatively, it can become worse, which has the good result of revealing the deviation from the good. A step in the wrong direction shows us the wrong direction, and this is good because it is necessary. There is a standard of “bad” that results from doing bad, which is not good because the result is outside it as the good. And therefore, the bad has the good outcome of unveiling itself. However, we still have not addressed what is actually unveiled—what is the bad?

The bad is not simply the negative outcome for a particular agent; it also holds a universal place in relation to the good as the ultimate standard. Doing something is its own good. However, if we go further and say that doing something bad would have been better left undone, we must still acknowledge that to know it is bad, it has to at least be done—or, rather, it must exist. Here, we are associating doing something with something merely existing without knowing the action that led it into being.

If we counter this by saying that a killer had the aim to murder, how can we claim that carrying out the deed—actually doing it—supports the idea that doing is a good in itself, when the act in this case is murder? The concern here is not that there should be no bad things at all, because that is not only a fantasy but also a misunderstanding of the nature of bad things. On an infinite scale, there are as many bad events as good events, and this is why the development of the particular is a remedy to this contradiction.

Real Time

The universal made itself into a particular whose timeline is a constant “unfolding” in the present moment, experiencing events in “real time.” This is a real element of time. The uncertainty arising from the infinity of equally ‘bad and good’ events requires a particular element to be in the middle of that, constantly determining one over the other. The universal developed into a ‘particular’ so that it could have the capacity to determine generally good events over bad ones, or, in some cases, generally bad events over good ones. In either case, there is now the capacity to choose one side over the other, rather than facing an infinite indeterminacy with all standards of events being equally valid. The logic of this follows in this sense:

Positive as deviating from the negative but not deviating from itself.

If we begin from a purely negative starting point, then any other course of action is positive. As the saying goes, “it cannot get any worse” (— results in +—). The negative, deviating from itself, becomes positive. If I am negative towards a negative, then I am positive. A positive is a deviation from the negative, constituting the force that deviates from the negative. In that sense, a positive is now something positive (+— results in ++), which, unlike a double negative, is not something other than itself. A double positive results in positive, while a double negative results in positive. Both the deviation away from the negative and the deviation towards the positive are essentially the same. Being positive is the quality of not deviating from one’s own identity. Yet the negative deviates so that the positive does not.

Bad things are “failings” of good things, and so they start out as good or, at the very least, have the good of starting something at all. But they deviate into being done badly, which is opposed to excellence. When you start something, you cannot undo it, and therefore, you have no choice but to do it. If not the same thing, then something else—but doing nothing at all is itself a doing. In the context of doing, doing nothing is bad. This is where doing it badly comes in: if you have no choice but to do something, since you are already doing, then you can either do it badly or well, both of which take different efforts as they are aspects of doing.

Bad has the hardship of suffering the consequences, while good has the difficulty of practicing excellence. For example, staying physically healthy requires enduring the pain of working out, while being unhealthy suffers the pain of illness. It is in this capacity that we can judge something to be good or bad. When you are doing something bad, you have chosen to do that over doing something good, because you had no choice but to do something to begin with.

If they know the ‘good’, why would they do the ‘bad’?

Metaphysics is not in “search of the truth” but rather in favor of it. There is the classical Socratic notion which argues that those who do bad are “ignorant” because, if they truly knew the good, why would they commit the bad? For example, why would someone who can play beautiful piano music play it badly? But this idea is not meant to suggest that bad people are unaware of what they are doing. The common understanding of the term ignorance, when used as an adjective, refers to someone lacking information; ignorance in this sense is accidental. However, when ignorance is used as a verb, it means to ignore—to deliberately pay no attention to—precisely meaning that someone knows the good but chooses otherwise. This is why ignorance, in this sense, is associated with the moral deficiency of vice.

The question of asking what is true is the same as asking what is good.

(William James: choice 1.2.3 “faith in reason”)

The ethical aspect of the rational notion requires there to be a choice—not in the sense of merely selecting one object over another, like choosing a cake over an apple, but rather the will to choose. Being in the moment of having to make a decision is simply the product of a previous choice.

Outside of my choice

This places the observer in a situation where they must choose between certain options. We commonly claim that we are put in circumstances we did not choose, and then we must act accordingly. In other words, we must “adapt” to the environment. However, this idea—that we are placed into circumstances out of our control, which drives theories like Darwinian evolution—misses the fundamental role of the conception in determining the situation. The conception is the simultaneity of the choice being available in the first place. We cannot simply assume that being given a situation means that we’ve already made the choice. By conceiving a situation, we necessarily presuppose a set of options that must be chosen over others. We say, “You put yourself in that situation,” as if to suggest there are inevitable situations that will necessarily follow from being in a certain circumstance.

Causes are particular, effects are universal

How a general notion comes to take on particular forms refers to how the same self-identical conception—whether it be a set of things or no thing at all—organizes the arrangements of relations in a particular order. The distinction between the universal and the individual is not one where each is a separate category, but rather they represent different interactions of the same source. For example, we can consider our ordinary life as being arranged and organized by the individual, but, in turn, life also arranges and organizes the individual. The individual acts particularly or performs a series of particular actions that organize their life, but their life—or everything generally outside the individual—reciprocates back to the individual with effects. For example, entering a door and a door being entered are the same event, but not for the same entity. If you do bad things, bad things will happen, and vice versa. At a more general level, the life of the individual—their circumstances, events, and everyone else—constitutes the universal side relative to and for the individual.

The individual is part of the environment that acts in many ways. The general character of these actions, exhibited by their results, takes on a general character of its own that reciprocates back to the individual who initiated those finite actions. If you usually act violently, life will exhibit a generally violent vibe. We can express this relationship between the individual and the universal in the realm of time. We know that the past affects the future, but it is difficult to say how the future affects the past because the future has not yet happened. So, how can it affect something that has already happened? However, if we introduce the present as the moment that is neither yet the past nor the future, then what you do in the present is influenced by a potential.

Take an arbitrary example: tying your shoelace before you run. In the present moment, you tie the shoe in a clumsy manner, so that halfway through the run the shoelace gets untied, which interferes with your run. However, this gives you just enough time to rest, a rest you were unwilling to take because of your pride. Your future self influenced your decision to tie the shoelace loosely in anticipation of the potential that you would need rest, which you were unwilling to take, which the end result was made in order to enhance the overall run. We often wonder why certain things happen.

However, if we reflect back on the event and uncover all its mechanics, we come to understand why the events that took place in the past forward the future. Everything, when looked back upon, ties into each other, even if it is not immediately obvious how they connect. But when we look into the future, there is complete uncertainty about how events will tie into each other. From the future, you cannot access the same kind of understanding of events that paints a rational picture. You only gain the potential for that series of events to unfold into a logical sequence, with reason stamped upon it in hindsight.

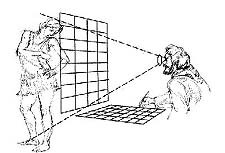

Things known in themselves

Peirce explains that Aristotle “was driven to his strange distinction between what is better known to Nature and what is better known to us.” Aristotle’s claim that things can be “known by nature” indicates that things exist in themselves, independent of whether or not any person knows them. However, there is also the presupposition that there is an implicit observer in things existing in themselves. While scientific knowledge begins with what is better known to us—based on what we sense and understand—it ultimately arrives at a comprehension of things better known in themselves. Science is the attempt to return to the level of the observer implicit in the thing existing in itself from an outside source. Science aims to make the observer one with the object. When we say “put yourself in the shoes of others”, in science, we are trying to put our mind in the “shoes” of the phenomena.

Be one with the spirit; be one with the force. In science, we are trying to be one with the object. In the same way that the same material is used to make other material objects, the mind uses its own substance to create other forms of itself. In this way, you partake in thought by being one with it, and you are one with thought when you are engaged in it.

How can I take hold of the phenomenon? How can I become one with it? How can my consciousness merge with the activity so that my identity becomes undistinguished from it? The answer to these presupposing questions lies in the twofold distinction mentioned above. Ultimately, by doing the activity, you become one with it, like engaging with intellectual activity, Aristotle use to say, its like “partaking in the activity of God”. We must move beyond what is better known by nature to what is better known in things themselves. The assumption is that things known by nature are not the true things in and of themselves because our natural capacities are limited to what is given by their nature. Reason takes these capacities and expands them, moving beyond the limitations of sensory perception into the realm of things known in themselves—the forms.

Growth – Truth is Conceived

Authors often mistakenly believe that their intellectual work somehow produces truth from where it did not exist before. But truth is not created in the same way that an object is produced. Truth is not “made,” per se; it is conceived. This is what it means to be “made” in the true sense of the word, because an object is made by way of another object—the material of one object is used to make another. But “conceiving” means that something truly originates from nothing other than the same material. This means that what makes the conception and the conception itself are the same thing. As we say, you conceived yourself into being: you came from your mother, but you also conceived your mother in the sense that she is a part of your life, and you conceived your life as a variable within it.

This perspective arises from issues with the image of the world as something created (Alan Watts 6:32). We might also consider how science has kept the law but removed the lawmaker.

The process of “creating” works from the outside to the inside, like arranging parts together to form a whole. In contrast, the nature of growth works from the inside to the outside, like a seed blossoming into a more complex organism.

Growth complicates itself, but from a purely practical standpoint, a vulgar pragmatist might ask: Why would something need to complicate itself? Is it not the “practical” (or pragmatic) concern to simplify the activity, rather than complicate it? For example, in alignment with the mathematical task of “simplification,” where we reduce a multivariable fraction to a single or direct answer.

God – Monotheism vs Polytheism

Monotheism has influenced the common idea that one substance, one “God,” has created all things. However, all descriptions of ‘God’ never take on a singular meaning. In Christianity, for example, we have “God the Son, God the Father, and God the Holy Spirit,” as if God is the same substance that takes all these different forms. Similarly, in Islam, God is associated with “99 names,” which are called attributes of God, such as “God the Merciful, God the Witness, God the Creator of the Universe and all matter,” etc., indicating that God possesses all possible descriptions and infinitely more. Before monotheism, older religions, like Hinduism, believed that all things were god(s), or that each single entity was a god. This is why, for instance, animals were worshipped—a practice that monotheistic religions strongly oppose.

The idea that every single thing is its own “god” means that it created itself. This belief eventually developed into monotheism, which requires an overarching substance that unites each specific thing into categories. This disagreement between mono versus poly reilgions dates back to pre-Socratic times and is perhaps the oldest philosophical conflict in history: Is “God” a single substance in the universe, or are there an infinite number of “gods”? This is the difference between monotheism and polytheism.

When monotheists appreciate the beauty of a natural object, like a tree, they may say, “It is the great work of God; look at how beautiful God made it.” This separates the process of creation from the result, with the process attributed to God, while the object is seen as the subordinate instance of that process. The reason for this is that the “process” transcends the objects it produces and can “create” something else (other objects). In contrast, in order for the object to change, it would not be what it “is” and would be limited to itself.

God is associated with the capacity to transcend the limited result of an object, but the problem is that the process is specific to the object itself. In other words, the object involves all the ingredients or sequences of behavior that constitute the process. Old polytheistic religions would say that the object is its own god because it involves that process. For example, if you leave a fruit out for several days and then return to find it has grown bacteria or maggots, the bacteria did not necessarily come from outside the fruit. They did not travel to it like a fly, but grew from within it. At some point, they were part of the fruit, evolving as part of its decay process.

Doing the activity for its own sake, or for the sake of something ‘other’?

The kind of “practicality” that aims to simplify complexity concerns instrumental activities, whose aim is to produce results that, once attained, nullify the need for the activity. Instrumental activities are unsustainable without the kind of “Reason” attained by activities done for their own sake, whose results become the standard for continuity. An “end-in-itself” activity is done for its own sake and, therefore, sustains its own purpose by having that very purpose as the aim of the activity. In this sense, everything is made for the sake of that end.

There are two moral reasons why individuals partake in activities:

- First, if the activity is only done to attain some desired end, it is important to first wonder why that result is an object of desire.

- Second, if the activity is done for its own sake, then the participant must first ask whether they truly want to do the activity. The very lack of wanting to do it negates the fact that the activity is done for its own sake.

Doing the activity for some other sake is not truly doing it at all, because in that case, you are improperly doing some other activity. The activity cannot be its own end if it is not a desired aim. Yet, the desire for the result is an end independent of the process of the activity. The real question, then, is whether what you want to do is given or acquired.

Thought is the first action

Thoughts are the actions of physical things

“Lust committed in thy (his) heart.”

There is a Christian notion that something is first committed in the mind before it is carried out in conduct. In other words, the standard for doing something is satisfied by conceiving it in the mind first, before it is acted upon in reality. In this sense, thought is the first action and the first form of doing something.

We are all familiar with the famous maxim in the Bible: “That whosoever looketh on a woman to lust after her hath committed adultery with her already in his heart” (Matthew 5:28). The modern perspective often views this idea as extreme because it is commonly assumed that thoughts have no bearing on reality. There is a strict separation between what goes on in my head and what happens outside my body in the world.

We say, “I can think of anything I want, and no one will know, nor will it affect what happens in reality.” After all, “they are just thoughts.”

This is the attitude we carry in our internal perception. But the Ancients did NOT take this distinction as literally as we do today. Perhaps even before the ancient Greeks, and certainly within the Christian tradition, all thoughts were understood to be known—if not by someone else, then by the person thinking them. And that, alone, constituted a cause for reality.

Most of our practical maxims in society depend on the relation between mind and reality being more of a unity than a duality. For example, in common law due process, which has a strong Christian influence, mens rea—the “guilty mind”—sometimes brings harsher punishment than actus reus, the physical act. In the case of attempted murder, the punishment can be more severe than that for manslaughter resulting from negligence. The idea is that intention is more real than the action, because the mind is the cause of the action. Or rather, that deliberation—such as in the case of first-degree murder—is the strongest ground for conviction.

Discoveries

Searching for the truth has the correct connotation if it implies that we do not yet know how to explain what we know to be true. This is why all great scientific achievements are labeled as “discoveries”—because the idea is that truth becomes knowledge. We become aware of what already exists, or what has always existed: universal knowledge. However, the conception of it reveals not only how it has always existed but also how it always comes into being. This is the dilemma that metaphysics addresses.

Truth involves the precondition for something to be self-evident, but this possibility for self-evidence should not be confused with the fact that it is present. The mere presence of a thing is not indicative of what it truly is.

Images of Objects

It is a trick of language that a word must bring up an image of an object in the mind. Hegel says:

“But their complaint that philosophy is unintelligible is as much due to another reason, and that is an impatient wish to have before them as a mental picture that which is in the mind as a thought or notion. When people are asked to apprehend some notion, they often complain that they do not know what they have to think. But the fact is that in a notion there is nothing further to be thought than the notion itself.”

Words are meant to communicate shared experiences of objects, but that should not lead to the presupposition that truth is only about pointing at objects, nor is truth merely reduced to what is presented as “images” of objects in the mind. Even in language, no word is limited to referring to just one kind of object. Every word can be used to refer to different objects that share similarities. Moreover, an image in the mind can arise and represent one or more objects

Words group objects based on a common feature they share, such as a function or an attribute, which are not necessarily physical aspects. Depending on the specific context of its use, a word will point to a particular object it is related to. Therefore, words describe relations between objects because we view an object not merely as it is presented but also in terms of its position at a particular stage in a timeline. For example, when we look at a child, we do not just refer to them as a ‘little person’ based solely on their height, but rather see them as being at an early stage of development, potentially becoming an adult.

Unintelligibility

Just because an object is differentiated and singled out from other objects — which is the natural precondition for understanding something — that alone does not make it known. We often say there is ‘more than meets the eye’ because a single object is a scope for an infinity of other details, and truth must disclose knowledge of all these. Hegel describes the difficulty in philosophy as stemming from an incapacity for thinking abstractly. He says:

“This difference will to some extent explain what people call the unintelligibility of philosophy. Their difficulty lies partly in an incapacity — which in itself is nothing but a lack of habit — for abstract thinking; i.e., in an inability to get hold of pure thoughts and move about in them. In our ordinary state of mind, the thoughts are clothed upon and made one with the sensuous or spiritual material of the hour; and in reflection, meditation, and general reasoning, we introduce a blend of thoughts with feelings, percepts, and mental images. (Thus, in propositions where the subject matter is due to the senses — e.g., ‘This leaf is green’ — we introduce categories such as being and individuality.) But it is a very different thing to make the thoughts pure and simple our object.”

Thoughts arise in the mind as images of objects experienced in daily life, but this is simply a way the mind uses available material to communicate meaning with the observer. Hegel explains that the difficulty with thinking in a ‘philosophical way’ stems from a lack of habit in understanding the nature of what we take as the object of thought. Normally, we assume that ‘thought’ is generated from objects we experience through the senses, and then later, thought imposes on them concepts that we consider abstract, which are entirely separate from what we perceive as concrete, sensory objects. However, the failure to recognize the true abstract as ‘pure thought’ results from an inability ‘to get hold of pure thoughts and move about in them.’ Once the mind, through habit, becomes oriented toward making “pure and simple thoughts our object,” the process of philosophical thinking becomes clearer.

Dream Analysis

In the psychoanalytical study of dream analysis, the mind uses imagery to communicate meaning. What is considered ‘real’ in a dream does not carry the same content of reality as in waking conscious experience. For example, while an owl in normal daily experience might simply indicate itself, in dreams it may symbolize wisdom. Moreover, what constitutes facts in normal waking life, such as ‘the boy walks down the street,’ is self-evident because it is happening, and it is assumed that what is happening makes sense and has a rationale behind it. But in dreams, the truth of the facts is not derived from what is occurring in the event. In most cases, what happens in dreams does not follow the standard of events having an obvious connection. For example, I might push a cup off the table, and it naturally falls, but in a dream, my pushing the cup could trigger an entirely different event, leading to a new scenario.