First updated 08.12.24

Introductory Descriptive

Do not, however, let the word “introductory” suggest a simple or brief task. Unlike other sciences, introductory works in metaphysics have historically proven to be among the most demanding. As Hegel says, the ‘entire science of metaphysics is an introduction’.

Modern pedagogy has become so descriptive that an obvious starting point is often overlooked. Specifically, it has become customary to develop a “descriptive” account of the subject-matter before inquiring into its essential nature. However, this approach is challenged by a natural intuition that urges curiosity: what is the point of describing something in the first place without first understanding its essential nature? Moreover, how valuable is a description of something if it does not capture its essential nature? In this way, science faces a conundrum.

Should science be descriptive and then normative, or should it remain purely analytical and refrain from making moral judgments? One approach is for science to ignore these differences at the outset and refrain from making them the focus of preliminary reflection. Instead, such differences will naturally emerge through investigation and the development of the science itself. This approach raises the question: in what way are these so-called preliminary reflections any different from other facts that science seeks to uncover?

The aim of this inquiry is not entirely descriptive; it seeks to do more than just offer an exposition of the views of certain philosophers. While much of this inquiry draws from particular traditions of thought—especially the relationship between ancient and modern ideas, such as those from Ancient Greece and Modern philosophy—its primary focus is to examine works from these thinkers that provide a normative investigation into what constitutes the essential nature of development in the world. Furthermore, this inquiry aims to serve as an introductory proposal for the science of metaphysics, laying the foundational logic and forms of thinking necessary to make substantial claims about the essential nature of our world.

2.1 Surveying of Opinions

The science of ontology today has been reduced to the “surveying” of differing viewpoints on the nature of reality. At the same time, it is commonly implied that there is no single “view” better than all others. While all viewpoints may be equal in the sense that they are mere thoughts, this is not the same as suggesting that all forms of thought are equally viable in being true.

Not all thoughts are of equal merit. Just because there are many viewpoints does not mean they are all equally true. They are equally necessary does not mean that they are necessarily equal. There may be many beliefs about the nature of reality, but there can only be a relatively few true conceptions of what it actually is. Even the same person can speak truthfully at one point but then fail and speak falsely at another. The goal is to develop the skill to differentiate between the two. Philosophical encyclopedias grapple with the issue of constructing a comprehensive selection of knowledge that is logically true before being true in any other way.

2.2 Normal Encyclopedia

Normal encyclopedias gather all the information relevant to a general topic and offer the convenience of having the information “there” (readily available) when the topic is searched. However, they do not provide a “worldview” about the nature of reality. They make no effort to “negate” or critically question the particular facts in order to construct a general picture of the whole topic. They do not delve into the deeper aspects of the subject matter because they may get lost or make an error, and they cannot “risk” making a mistake while trying to provide “impartial” facts for the learner. However, being truly impartial is impossible because any fact presupposes some ontology, whether directly or indirectly. Even modern internet search engines like Google pretend to offer impartial “results” on a topic, when in reality, these results are selected, regulated, and monitored to align with a certain ontology (or narrative) of the time.

The way normal encyclopedias ‘select’ information is more ‘accidental’ than principled, as they compile a set of viewpoints and present those as equal facts, leaving the reader to form their own opinion about what is being presented. Being “normative” is either accidental or pretends to be accidental, because the selection of certain facts will inevitably exclude others. For example, if I choose to only study law, I will inevitably ignore biology and chemistry. However, every science naturally presupposes the facts from every other science.

The point is that the act of selection itself inherently excludes. It is impossible to be “impartial” when presenting a theory because the author must either assume their idea is true or assume that it is true that their idea is untrue. In the meantime, they must exclude other theories not being presented as irrelevant.

2.3 Philosophical Encyclopedia

A philosophical encyclopedia operates on the ‘prejudice’ that there is such a thing as “right and wrong” knowledge. Whether there is “true or false” knowledge becomes a subject-matter that will become clearer throughout the course of the inquiry. However, it is nevertheless an assumption that ontology operates on the idea of ‘gathering’ information and formulating this “information” into a conceivable event (moment) externally presented for the observer as a phenomenon (object). The object possesses two components: Form (thought) and matter (physics). These two are among the fundamental “topics” of ontology (the basic branch of philosophy).

Normal encyclopedias avoid questions of “why” and instead ask only “how things work?” For example, a doctor does not ask the patient why they smoke; the doctor simply reviews the disorder in front of them and performs the necessary operations to alleviate it, much like a mechanic fixes a broken car. The mechanic does not ask why the car got into an accident, but simply replaces the broken parts to restore the vehicle.

Hegel distinguishes a philosophical encyclopedia from an ordinary encyclopedia, he says:

“The encyclopaedia of philosophy must not be confounded with ordinary encyclopaedias. An ordinary encyclopaedia does not pretend to be more than an aggregation of sciences, regulated by no principle, and merely as experience offers them. Sometimes it even includes what merely bear the name of sciences, while they are nothing more than a collection of bits of information. In an aggregate like this, the several branches of knowledge owe their place in the encyclopaedia to extrinsic reasons, and their unity is therefore artificial: they are arranged, but we cannot say they form a system. For the same reason, especially as the materials to be combined also depend upon no one rule or principle, the arrangement is at best an experiment, and will always exhibit inequalities” (Hegel Encyclopaedia of the Philosophical Sciences 1830 16)

A philosophical encyclopedia is a mechanism of selecting in, and filtering out, certain truth(s) within a body of knowledge, and in this way, it is a system of thought and NOT just “a collection of bits of information”. Philosophical encyclopedia is governed by principle.

Medical Encyclopedia

A “medical” encyclopedia, for instance, provides information on different types of diseases, their symptoms, treatments, and prognosis. However, it does not delve into the deeper question of why certain human behaviors lead to health issues. This question belongs to the realm of ethics, which addresses how to stay healthy and avoid sickness in the first place. But for a science intended to alleviate sickness, it does not address what is necessary to avoid being sick. This could be due to two reasons: (1) the business of sickness is purposely maintained to profit from it, or (2) it assumes that ethics is a topic beyond its specific subject matter. Either of these approaches is problematic because they are reactive — resolving an issue after it has already arisen — rather than proactive — behaving in ways that prevent the issue from occurring. Of course, the latter is idealistic, as problems will always naturally arise, whether avoidable or not, but that does not change the need to resolve them. Psychoanalysis, for instance, addresses these deeper questions about the person, and therefore it can be considered a proper ontological science, if done correctly.

If ethics is disconnected from truth (in this case, science), then science as an enterprise is prone to corruption, like all other human endeavors, if they are unethical — meaning they operate against the truth or use the truth to undermine it. When science becomes corrupt, the idea of “impartiality” is misused. A body of science (or propaganda) may pretend that ‘no’ worldview is being declared, when in fact, behind the scenes, a certain ontology (worldview) is being perpetuated — one that you may not want. The truth is a battleground of conceptions, and the conception that determines the present state of reality may also be the most predatory (unethical). On the other hand, the ethical side may also act “behind the scenes” to correct deviations from the truth and bring them into the light of Reason. The latter is the ultimate task of “Ontology”: the study of ‘how’ two things exist (into Being).

2.4 Ontological Encyclopedia

Ontology does not find the “Truth” later, after searching for it. Metaphysics assumes that Truth is first, even if we do not ‘know’ it. The truth is still self-evident, independently of our knowledge of it; and then the thinker “finds” the truth during an experience, by confirming what is already there for the truth (the moment) with his own internal thinking (his mind). In other words, the thinker rediscovers and becomes aware of a mental phenomenon in the “real” world. Hegel argues that the power of philosophy relies on the notion of the “ought.” He writes:

“The ought plays an important role in philosophy, especially in connection with morality and also in metaphysics generally, as the ultimate and absolute concept of the identity which in-itself has self-relation. The determinateness or limit.” 263 […] ‘You can, because you ought’ — this expression, which is supposed to mean a great deal, is implied in the notion of ought. For the ought implies that one is superior to the limitation; in it the limit is sublated and the in-itself of the ought is thus an identical self-relation, and hence the abstraction of ‘can’. But conversely, it is equally correct that: ‘you cannot, just because you ought.’ For in the ought, the limitation as limitation is equally implied; the said formalism of possibility has, in the limitation, a reality, a qualitative otherness opposed to it and the relation of each to the other is a contradiction, and thus a ‘cannot’, or rather an impossibility.”

The differentiation between “true or false” knowledge is by no means an easy task. However, “one thing is for sure”: according to ontology, the first wrong move is to assume that there are no wrong moves. In other words, the assumption that there is no “right and wrong” is itself the first wrong, because judgments about the negation of truth also make a claim about the truth, i.e., they are positive in their affirmation.

2.5 There is “NO TRUTH”?

Whether we say there “is truth” or there is “no truth,” both presuppose the topic of Truth, with one claim being the positive and the other the negative of the same principle. The lack of “a thing” does not remove it from existence. There is still a place for it; where it is “not” is a place where something else exists. Thought “ought” to transcend the limitations it has imposed upon itself. Hegel says:

“In the Ought, the transcendence of finitude, that is, infinity, begins. The Ought is that which, in further development, exhibits itself in accordance with the said impossibility as infinity.” […] With respect to the form of limitation and the Ought, two prejudices can be criticized in more detail. First of all, great stress is laid on the limitations of thought, reason, and so on, and it is asserted that the limitation cannot be transcended. *To make such an assertion is to be unaware that the very fact that something is determined as a limitation implies that the limitation is already transcended. For a determinateness, a limit, is determined as a limitation only in opposition to its other in general, that is, in opposition to that which is free from the limitation; the other of a limitation is precisely the being beyond it.” (264-265)

The latter claim speaks to what is known as an “affirmative contradiction,” which is a fallacy constituting many misapplied notions of logic. The choice of one option over another does not exclude the relation, or lack of relation, between two or more principles. Modes of thinking, like “assumptions” for example, are actions that operate on a logical basis.

2.6 The First Move

The first right move is the assumption that there are “right and wrong” moves, because that is the recognition, or confirmation, of what is already “there” for truth. These are truths, also known as “recognitions,” because they are primarily mental phenomena that the philosopher must first adopt before selecting information they judge to be true or false. Hegel says:

“In the form of an Encyclopaedia, the science has no room for a detailed exposition of particulars and must be limited to setting forth the commencement of the special sciences and the notions of cardinal importance in them.” (Hegel, Encyclopaedia, p. 16)

A body of knowledge involves selecting ‘in’ and filtering ‘out’ truths.

A philosophical encyclopedia is a mechanism for selecting in, and filtering out, certain truths within a body of knowledge. In this way, it is a system of thought, not just “a collection of bits of information.” Hegel distinguishes a philosophical encyclopedia from an ordinary encyclopedia, stating:

“The encyclopaedia of philosophy must not be confounded with ordinary encyclopaedias. An ordinary encyclopaedia does not pretend to be more than an aggregation of sciences, regulated by no principle, and merely as experience offers them. Sometimes it even includes what merely bears the name of sciences, while they are nothing more than a collection of bits of information. In an aggregate like this, the several branches of knowledge owe their place in the encyclopaedia to extrinsic reasons, and their unity is therefore artificial: they are arranged, but we cannot say they form a system. For the same reason, especially as the materials to be combined also depend upon no one rule or principle, the arrangement is at best an experiment and will always exhibit inequalities.” (Hegel, Encyclopaedia of the Philosophical Sciences, 1830, p. 16)

A philosophical encyclopedia is always premised on a fundamental principle. Ontology tells the reader a definite worldview and is not here to offer differing viewpoints for the reader to decide for themselves which one is true. Whether the reader agrees or disagrees will naturally follow from their own self-critical thinking.

2.7 Offer them an “environment”

Ontology is not meant to provide an environment where the reader can simply decide and have an opinion on what is presented, because that misses the point of metaphysics. Ontology aims to uncover truths that the individual already unconsciously knows exist, but has no proof for or is unaware of. To proceed with actually “proving” the truth is identical with coming to consciousness of it. The driving principle is to prove and demonstrate truth, and for that reason, it is necessary to assume: a) that “there is truth,” and b) to proceed as if it can be proven.

In our Modern academic setting, students are encouraged to approach philosophical texts with a “subjective” attitude, meaning that the “truth” behind the words is ‘open’ to interpretation and varies from person to person. The system is structured around this ontological standpoint, preventing an objective criteria for pointing out falsities in the authoritarian narrative being perpetuated onto the impressionable masses.

When “truth” is said to be subjective, this ontological standpoint is a “sleight of hand” employed by educational authorities to obscure Ancient texts. They allow “teachers” to impose their own subjective interpretations on texts that are inherently meant to provide an objective outlook on the nature of reality. The subjective opinions about these ancient texts take the place of the actual texts, using the ancient wisdom only in name. The subjective muddles the truth, taking its place. The subjective will always obscure the universal truth with a particular narrative they are trying to perpetuate, whether for personal gain, naïve reasons, or, in some rare cases, the actualization of some real “truth.” The classroom is not a place for truth, but a battleground of ideas, where the rhetoric of one idea overcomes another. Truth is experienced internally by the individual and is carried out through their productive (artistic) forces—what they actually accomplish in the world, i.e., what they bring into being.

The term “subjective”

When we say something is “subjective,” it points to something “personal” that no one else has access to, except the individual experiencing it. However, this definition is shallow and limited, because the term “subjective” also bears an objective significance. First, the subject is an “object” in relation to others. Second, what he experiences as “personal” is also an external, objective phenomenon, conceived by others. At a fundamental level, occupying a particular position in space and having a definite length of time (rate) constitutes the sequence of mind.

The content of metaphysics cannot be confined to specific periods in history, but instead maintains a common principle prevalent across all traditions through the ages. This does not mean that all traditions postulate the exact same ideas, but within each unique notion of a tradition, there are the same disagreements about the same fundamental principles. The science of ontology is founded on the principle that thought (reason) determines reality, and that everything in the known universe is fundamentally first an abstract conception before becoming an object experienced by sensation. The entire “subjective” experience is objectively based on this reality of universals. The subjective is the avenue that the universal passes through its its medium, and through that medium, it also changes itself into another objective reality.

2.8 History of Philosophy

Unlike other specialized studies, such as the “history of philosophy,” we do not focus on certain time periods over others because we are only interested in finding knowledge that is consistent with our principle, from philosophers at any time in history. The latter matter is the subject of the “philosophy of history”—the philosophy about the concept of “history,” and not just “history” as the record-keeping of events, but the idea that events follow a particular order and purpose in time.

The history of “mankind,” the rational species, is an ontological science because it is searching for the “common principle” across all different periods of human history. The common principle across all ages.

The study of ontology looks for more than a set of already present opinions about the nature of Being; it looks for the nature that enables such differing conceptions in the first place. It is oxymoronic to say that science is the “survey of different opinions about Being” without there being a universal notion to which these opinions are based on. The history of philosophy stands on the notion that there is one truth—universal, absolute—and this truth is the fact that Reason governs the world; that the material world is first and foremost rational, created by the conception of an ultimate mind in nature. Any other view is either an elaboration of this, or a contradiction to it.

Micro concept

Truth, for us, is eternal, so the “context” does not matter first; rather, the “juice” is what we strive for. The famous American writer Charles Bukowski puts this perfectly in his statement about writing. He says:

“Each line must be full of a delicious little juice—flavour. They must be full of power; they must make you want to turn a page.”

The history of philosophy does not present to us a field of different perspectives about the nature of reality from which we get to choose and use to form an opinion about the world. This view is a modern assumption that falsely treats “truth” as a set of options from which we can select. Truth does not consist of options; it is more absolute than that. Truth is either rational or not, good or bad, comprehensible or incomprehensible, and if it is either one or the other, then it is a matter of degree between these extremes. The context of knowledge in history is pointed out to reveal either authors who exhibit deviations from the truth or authors who are protectors of the truth.

In more recent times, post-modern ontologies argue that each viewpoint is seen as an equal constituent in the dialogue about Truth simply because the views are present. For the post-modernist, the mere presence of an argument renders it true.

2.9 Methodological Scepticism

Hegel — “Learning to Swim Before Jumping into the Water”

Hegel critiques any method that attempts to establish knowledge before the activity of knowing, as in the case of “methodological skepticism,” famously formulated by René Descartes. Methodological skepticism is the ontology of critiquing the method itself, rather than the content of the truth. The way to arrive at the truth is as important as the truth itself, which is received after undergoing the process. Skepticism of methodology aims to solve a “paradox” in thought (logic) concerning the achievement of “truth,” whether it is prior to or independent of “experience.” Hegel likens this method to the act of trying to “learn to swim before jumping into the water.” He writes:

“It is natural to suppose that, before philosophy enters upon its subject proper — namely, the actual knowledge of what truly is — it is necessary to first come to an understanding concerning knowledge, which is looked upon as the instrument by which to take possession of the Absolute, or as the means through which to gain a sight of it. The apprehension seems legitimate, on the one hand, that there may be various kinds of knowledge, among which one might be better adapted than another for the attainment of our purpose — and thus a wrong choice is possible. On the other hand, that, since knowing is a faculty of a definite kind and with a determinate range, without the more precise determination of its nature and limits, we might grasp clouds of error instead of the heaven of truth.” (Hegel, Philosophy of Mind, p. 73)

“Knowing the truth before Experience”

The “A priori” problem dominated the early stages of Modern science, beginning with René Descartes’ requirement to know the truth of an experience without personally undergoing the actual experience. Experiences are objective phenomena that can be understood irrespective of their occurrence; they can be theoretically known. However, this raises the question: they must still exist at some point in time for them to even be theoretical, or the abstract conception of them is still a form of existence (happening). This becomes especially clear in our modern age with virtual reality. In an augmented reality” (VR) you are having an experience of an event without physically gone through it.

Events might not need to happen to certain individuals, but they do happen generally. How can we derive the “truth” from experience? Do we really have to go through the experience in order to derive the “truth” from it? Can I derive the truth from the experience irrespective of whether it personally occurs to me or not? The next question is: can experience exist without the truth being derived from it? Can I truly be completely ignorant?

The failure in this “skepticism” lies not in the critique of the method, but in the misapprehension that doing the activity can somehow be separated from the result. Knowledge and the content of it, from which you find it, are one and the same. Hegel’s entire philosophy involves the method of resolving methodological skepticism, asserting that the method and the actual practice of the method are indistinguishable. You may have a blueprint before building the house, but the course of building the house also introduces knowledge that supplements the blueprint.

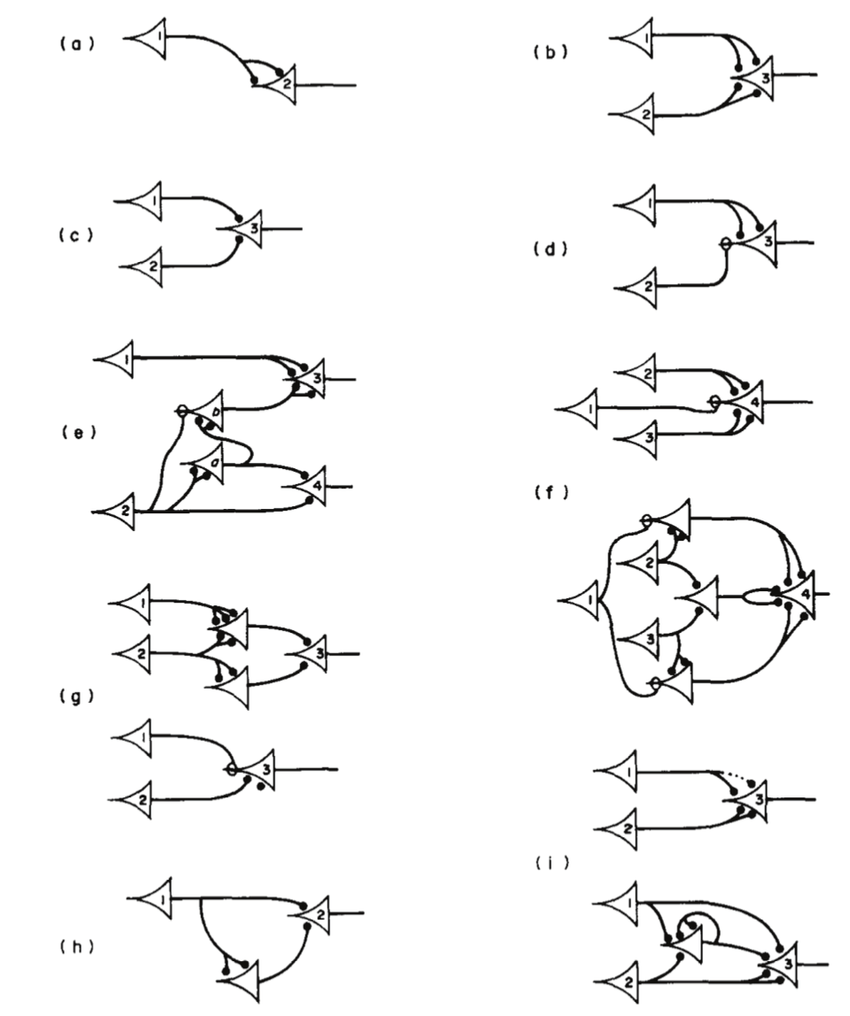

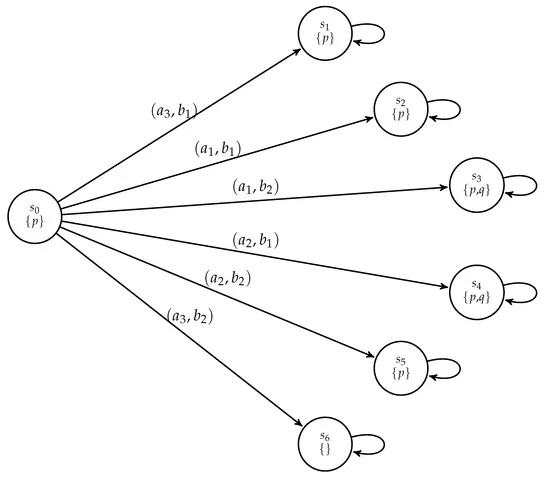

Mathematical vs. Logical Calculus

One can learn all about the theoretical applications of an event during an experience; however, the actual “going-through” the process—experiencing the event itself—is something the observer cannot truly understand unless they have personally experienced the event with their own consciousness. The method is separated from the subject so that one does not have to be completely accountable for the other. This creates a “safe” gateway that allows for many different ways (views) of arriving at the same answer, without distinguishing between the quality of those ways (views). For example, in mathematics, there are many ways to arrive at the same conclusion, but the “best” way is the fastest and therefore the shortest route to the answer. In contrast, in philosophy (logic), the opposite is true: a logical process must exhibit (show) all the steps (possibilities) that lead to the conclusion in order to be valid.

The fastest answer is not necessarily the best, and the longer time taken to contemplate the possibilties may perhaps be the better option. The maximum number of potential variables must be shown in a logical calculus so that all possibilities are considered, allowing for the selection of the best and most valid one. The reason why logic belongs to philosophy, and not to mathematics, is that logic must also involve—or presuppose—the field of ethics, which mathematics cannot measure. Ethics “controls” the rules of logic because the most rational decision is akin to the best one. There is a comparative value between “good” and “bad” variability. Ethics must be considered in the application of any field in science.

2.9 Language is the “enemy” of Metaphysics

We all know the famous claim made by Hegel that “language is the enemy of metaphysics,” because language often cannot precisely express the “idea” that is being comprehended by the thinker in their mind. However, language is also a tool for Metaphysics because embedded within language is logic, which serves as the foundation for all communication systems. The difficulty in communicating our thoughts with one another is almost as impossible a task as trying to transform something abstract into something concrete. For example, the ancient Greeks used to say that this type of thinking is the task of God (Aristotle).

The problems we encounter with language are, in fact, features of its informal logic. The so-called problem of how “language has come to use one and the same word for two opposite meanings” is, in truth, a philosophical feature. The defining “feature” of a philosophical concept, or even a “word,” is often that its definition contains two or more opposite meanings about the same topic. Take the philosophical concept of “sublation,” for instance.

2.10 Sublate

Hegel uses the word “sublate,” which is an important term in our inquiry, and it is a perfect example of how there is an implicit speculative meaning in our ordinary language. Words that have, in themselves, a speculative meaning. Hegel writes:

“The two definitions of ‘to sublate’ which we have given can be quoted as two dictionary meanings of this word. But it is certainly remarkable to find that a language has come to use one and the same word for two opposite meanings. It is a delight to speculative thought to find in language words that have, in themselves, a speculative meaning; the German language has a number of such words. The double meaning of the Latin tollere (which has become famous through the Ciceronian pun: tollendum est Octavium) does not go as far; its affirmative determination signifies only a lifting-up. Something is sublated only insofar as it has entered into unity with its opposite; in this more particular signification, as something reflected, it may fittingly be called a moment.” (Science of Logic, 186) […] “’To sublate’ has a twofold meaning in language: on the one hand, it means to preserve, to maintain; and equally, it also means to cause to cease, to put an end to. Even ‘to preserve’ includes a negative element, namely that something is removed from its influences in order to preserve it. Thus, what is sublated is at the same time preserved; it has only lost its immediacy but is not, on that account, annihilated.” (Hegel’s Logic, 185) Source

The point of the discussion above is to show that “words” inherently contain a philosophical (speculative) meaning, which is fundamentally logical. Words must be speculative so that they can allow for their replacements by meaning from other words, and therefore language is a transparency of substance. The idea of substance enters through itself to contain itself. Logic and philosophy go hand-in-hand because philosophy represents the final cause or the ultimate purpose of an argument in logic, while logic is the pragmatic and efficient way to express that notion.

2.11 Pragmatic logic

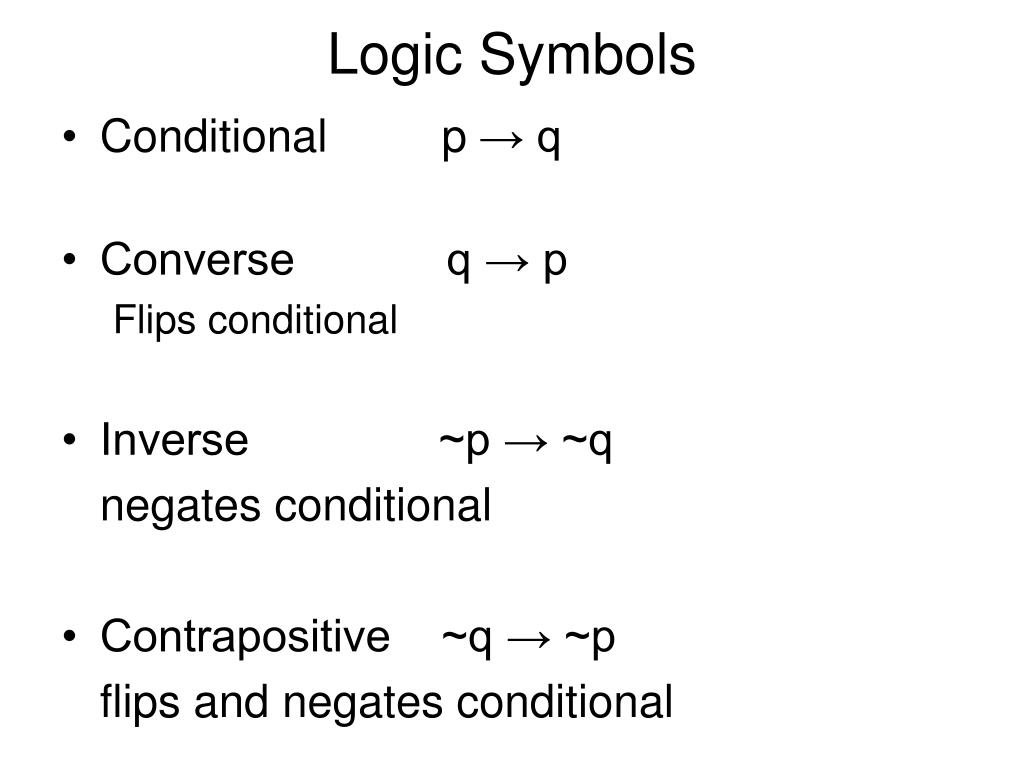

1.2.6.1

Logic is the pragmatic side of philosophy because it is fundamentally an ethically motivated conduct of thinking. Logic is the science of revealing all the possibilities that go into constituting the thought process. To reveal all possible outcomes is to be honest with the truth — to show everything, both the negative and the positive: the “good, the bad, and the ugly.”

This is why words always presuppose a double negative of meaning. They show everything they possibly can without leaving any potential unaddressed. All the potentials of a thing must be considered in logic.

It is an important preliminary point to pay special attention to how language is used to explain ideas. The purpose of language is NOT merely to determine (or explain) the idea; rather, language is meant to explain the determination of the idea in the mind. Involved in this task is the fact that, according to Alfred North Whitehead, language always speaks of purposes — that is, all words have, or tend toward, a purpose. We see this in the definitions of key terms. The word “language,” or “to gauge the lane,” is figuratively tied to the mental effort of determining a particular aspect of the truth.

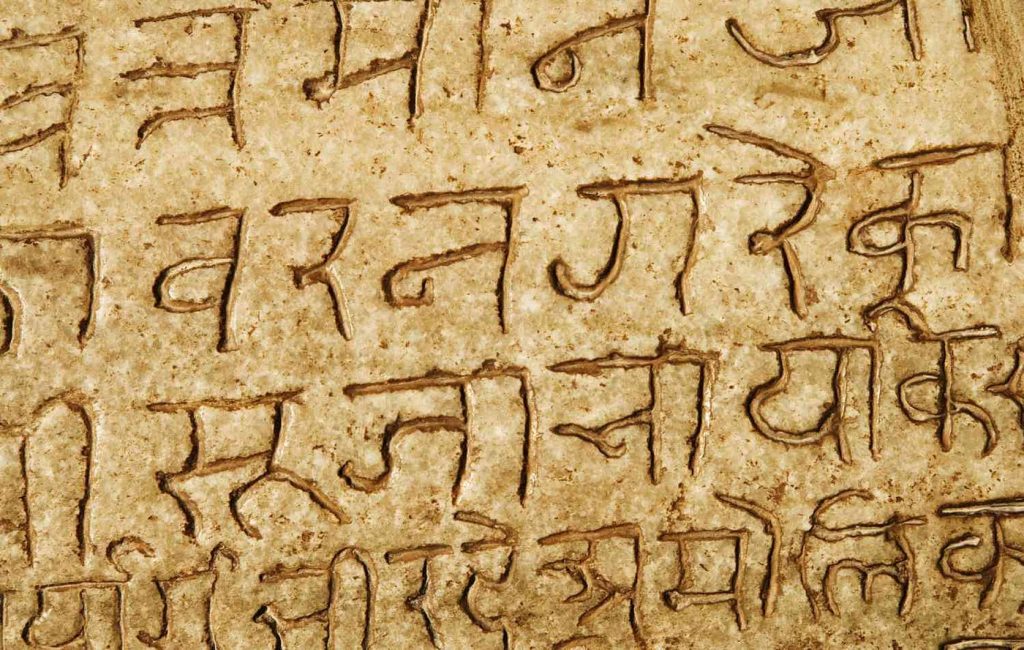

2.12 Terms

The “term” is merely a tool used to indicate the kind of “meaning” attributed to it. Without the meaning, a word is entirely semantically aesthetic — just scribbles, a means to an end, like wood without the form of a house. An important task in contemporary metaphysics is to associate ancient terms with their equivalent modern meanings. The difference in “sound” is superfluous if the meaning remains the same between two different terms. Just as two different languages use different words to describe the same thing, two different sounds are equally arbitrary if they convey the same meaning. The problem lies in the meaning.

Language is more complex than mere sounds trying to express the same meaning. The “meaning” is the problem because what you “mean,” or what the word is trying to express — i.e., the thought — is not inherently stable or static. It cannot be absolutely captured as one thing and not the other. Logically, any principle of “meaning” involves the fact that it is both what it is and what it is not, and that it is both the negation and affirmation of these over one another — that is, both together against each other, independent from the other, and each separate from the other, combined as a unity, but distinct.

In other words, the meaning of words is as fluid as the thoughts that express them. But the task of a “word” is to abstract this instability into a universally consistent (constant), communicable apperception of incoherence. The universal side of science, or what is meant by the “objectivity” of a fact, is the ultimate record-keeping of all the thoughts communicated and preserved between consciousness and itself. It does so in an infinity of different ways, each time for itself. But all these ways are fundamentally part of the same underlying substance — one that it does not know.

2.13 “Eudaimonia”- is a man truly happy?

Even though different languages use different words to refer to the same thing, the problem is that the “same thing” has an infinite number of dimensions. Therefore, talking about the same thing in two different languages still involves the challenge of addressing the same thing in different ways — that is, different aspects of the same thing. This is primarily the problem of translation, particularly when translating Ancient Greek terms that do not have a direct modern English equivalent. For example, “eudaimonia” represents a very different kind of “happiness” than the English word “happiness” seems to denote. The Modern term “happiness” is more closely aligned with what is called “positive emotions” in Modern psychology. For the Ancients, “happiness” does not necessarily correlate with emotions, but rather with a state of being — an overall experience (existence) of the observer.

Emotion, in its positive form, is identified by alterations in dopamine chemicals in the brain. After a certain activity is completed, an individual may experience euphoria, or a “moment” of absolute “peacefulness,” or conscious clarity. Our minds naturally create positive feelings after a task is completed. However, the ancient Greeks did not perceive “happiness” as merely chemical balances in the brain, because that alone does not explain the actual experience that the observer undergoes in order to have enlightened conceptions of thought.

The Ancient Greeks, particularly Aristotle, explained that happiness is not simply a collection of fleeting moments of “higher” experiences driven by positive emotions. That is, happiness is not just a feeling, but rather, first and foremost, it is an “ideal” conception that is universal — a concept. In this way, someone may experience moments of happiness, but their overall life can still be considered “bad.” For instance, if we witness a criminal being charitable in a random moment, we might mistakenly assume that the person is a “good” man. However, the truth is that, over the course of their life, they may have committed wicked acts and generally lived a brutish existence.

These lapses in judgment are problems arising from the tendency to view the world as a series of disconnected abstractions, which is how we perceive it through our senses. We experience the world in moments of sensations, constantly changing in degree and alternating between each other. The concept of happiness encompasses the whole of life, which can be understood as an instance denoting happiness. The concept is prior to the actualization of it, the Form before the matter. For the ancient Greeks, happiness is ultimately what you achieve and the person you become.

The interesting reality seems to be the inverse of this ancient intuition. It is observed that, as man ages, he often becomes a worse being rather than a better one. This is why the ancient Greeks emphasized that a “happy” (successful) man is one who becomes better (virtuous) rather than worse (vicious).

2.14 Only “Know a man once he is dead”

Aristotle argues that “we can only truly come to know a man once he is dead” (paraphrase). This is because, in death, we can see the totality of his life as a series of interconnected moments, each contributing to the narrative of what he has done, the successes and failures he has experienced, and the person he ultimately becomes after enduring all that struggle. We cannot truly come to know a man while he is living, because in that state, he is a malleable being, constantly being molded, changed, and formed. A man is always either becoming something other than himself or becoming more fully himself.

Man is not a stable being throughout the course of his life. For example, he may succeed in fulfilling his purpose at one moment, only to later fail. Conversely, he may initially fail to actualize his purpose, but eventually, over time, he may succeed. When a man dies, he becomes “eternal.” This does not mean that he lives on forever in a physical sense, but rather that the course of his life becomes abstracted and is recorded in history. His moral legacy can be reviewed by future generations. A true measure of a man is his consistency throughout his entire life in actualizing the “Good.” The “Good,” according to the ancient Greeks, defines the nature of mankind, a concept that will be discussed in greater detail later.

The overall life experience of an individual determines whether they are “happy” or not, but this formulation assumes that “happiness” can only ever be understood in the past tense—it is something that is realized only after it has passed. This notion remains valid, but it becomes erroneous only if we assume happiness is synonymous with emotion. If happiness is indivisible from positive emotions, then a person must be present in order to experience it. However, this is not ultimately true, because emotions are less fundamental in the overall mental experience of the observer than abstract thinking. Abstract thinking is a higher mental function than emotion, and thus more fundamental—meaning that the former must precede the latter in order for emotions to exist as they do.

What goal is achieved in order to produce changes in emotion?

An important task is to understand how terms and concepts elaborate on each other in meaning.

The quality of an experience is the most accurate measure of “happiness” because it transforms “happiness” into a true concept, or an “actual” concept, rather than a mere feeling. If we assume happiness is an “ideal”—a pure concept of thought (in Platonic terms, the Form(s))—then happiness, as an overall life experience, is the most accurate definition because it encapsulates the totality of events that an observer undergoes in the process of actualizing (or failing to actualize) their intended purpose.

2.15 Can psycho-active drugs be done moderately?

If “happiness” lacks purpose, then the mere experience of an emotion cannot measure whether a person has experienced fulfillment or not. For example, what “appears” to be positive emotions can sometimes be negative emotions lying dormant, as in the case of drug use. A person may appear happy on the outside, but feel empty and lost on the inside. Addiction can be described as a person lost within their own mind, as if their mind is an empty field in which they are aimlessly roaming, unable to find anything of meaning to give their life purpose.

At the onset, drugs provide “euphoria” without requiring the completion of any meaningful task to achieve the result. In other words, the brain is artificially stimulated by the chemical effects of the drug, such as the dopamine spike. Empirically, this meets the requirements for what is considered “happiness.” However, if we look at the overall quality of their life, we realize that they are trapped in extreme addiction and physical deterioration. When you see a homeless man on the street who seems “happy” (laughing) while high on drugs, do you really call that man happy? The answer is no, because his overall material circumstances suggest that he is, in fact, deeply unhappy.

The next question is not whether drugs are good or bad, because the obvious answer is that they can be both, depending on how they are consumed and the level of control exercised by the user. The problem with drugs—and any activity of that nature—is that the activity itself is inherently extreme. So, the real question is: how can one become moderate (or temperate) in an already immoderate (extreme) state? This is a more realistic question than the former because “moderation” in this case is simply a deviation away from an extreme position. To bring an extreme position to a more balanced one means going as far away from the extreme as possible, which leads to the following contradictions.

If I am moving as far away as possible from the most extreme position, that act in itself is “extreme” by nature, and thus would require further deviation from itself, and so on, indefinitely. This creates an “infinite regress” without any final resolution. Alternatively, in an extreme situation, the individual may act appropriately, which is considered “doing the right thing” given the circumstances. If this is true, then there are actions that one “ought” to take in any given situation, and in any activity, there are right and wrong ways to proceed. There is a way to “play the game,” as the saying goes. The proverb goes even further: “Do not hate the player, only the game.” In the case of the ancient virtue of “courage,” someone is courageous when they possess the willingness to confront a dangerous situation and act appropriately within an extreme case, with a desired outcome in mind.

If you never do drugs, your life experiences may be bland, limited, and boring, you’ll live life like a square even though you maintain your physical health. On the other hand, if you do drugs, you might experience intense highs, but you would likely struggle with moderation, addiction, and deteriorating health. The question then becomes: would you sacrifice your body to achieve heightened experiences in the mind, or would you choose a slower, more subdued mental experience while preserving your physical health? Is there a middle ground, a moderation, between these two extremes?

2.16 Language Style

Before embarking on the ontological understanding of scientific concepts, it is essential to demonstrate that language is not absolute, and that the meaning of a concept goes beyond its term. While the language used is not absolute, the concept it denotes is certainly absolute, as it seeks to reiterate a “universal” truth. The term “language” in this context encompasses mathematical, logical, and ordinary semantic discourse, as well as symbols and writing.

The first trivial matter in language is the style or format that, to begin with, dominates intellectual writing. In the academic realm, how well language conforms to a certain style is often seen as determining the merit of the argument. The style is taken to dictate the truth behind the words. However, even grammar is not so definite.

There are general foundations that explain what is grammatically correct, yet the application of such general rules can take on an infinite variety. For example, you are either grammatically correct or not, but you can be grammatically correct in “a million” ways, just as you can convey the same meaning in “a million” different ways—or be equally wrong in an infinite number of ways.

2.17 What is “love” (Philia)

Love, as a universal principle—and it is a principle because it serves as the foundation for a certain “state of being”—is universal when it is the substance that keeps everything in the universe intact. In other words, the relationships between all things are maintained by this notion of love. This general and vague definition of love, however, does not address the real need for a more specific definition meant to address the unique nature of human relationships, often labeled as morality or morals.

The philosophical encyclopedia is based on the ontology of three universal principles: Truth, Beauty, and Love. These concepts encompass all forms of thought and objects. (1) First, all objects (or things in the universe) exhibit Truth because they either exist or do not, and their existence denotes a meaning that can be apprehended by an observer outside of them. In other words, truth is objective. (2) Second, everything in nature exhibits an aesthetic value, meaning that it “appears” a certain way, and the appearance holds a value denoting either a “good” or “bad” nature. (3) Third, all things are related to all other things generally, and they bear specific relationships to certain things only, while lacking relations to others. The quality of these relationships, at its highest form, is expressed through the principle of “love.”

The word “love” has lost its meaning in modern times because it often characterizes a state of human affairs in a negative sense. We say, “there is no love,” or that “love is just an illusion,” when referring to the kind of feeling we have for others that does not exist, but which we assume must exist. Just as “eudaimonia” (happiness) is mistakenly associated with emotions (feelings) of pleasure in modern times, love is similarly confused with emotions (feelings) of lust. When love is reduced to lust, it ceases to be a virtue and becomes a vice, because lust is an animalistic instinct that does not reflect a rational conception of viewing others. For example, a lustful person sees others only as objects of pleasure, rather than as ends-in-themselves—beings who have intrinsic value outside of personal gain.

Love is often associated with human feelings and emotions. However, in its classical—Ancient Greek—usage, the term “love,” i.e., ϕιλία (philia), refers to a more universal meaning of proper relations. Love, as philia, is a rational conception of others because it is a “friendship” acquired over long periods of spending time together. You see the person as an end-in-themselves, and not as a means to fulfill some personal desire or gain. When you see people as “friends,” you wish for them what you would wish for yourself. They become an “other” self—i.e., the same self, but in another form. Of course, this relationship is not merely given; it is acquired through years of acquaintance and shared challenges or hardships.

Morality is the study of acting in the right or wrong way. Ethics, however, is the broader science that deals with the nature of relations between any two or more beings in the universe. There remains the presumption that love implies an inherently positive meaning, that it is not just any kind of relation, but necessarily a positively ethical one—a “good” one, rather than an antagonistic one.

2.18 The Idea of “man”

The word “Man” is classically used to signify the ideal state of human nature. Man represents the closest being to actualizing the essence of human nature. This does not mean that woman does not contribute to the actualization of human nature; on the contrary, the role of women is as important for the development of man as man is for the actualization of his essence. The relationship between the genders and their roles in actualizing human nature can be summed up by the following proverb:

“They are equally necessary, but not necessarily equal.”

Nature designates different roles for the genders in the evolution of human nature. Man is appointed the role of “determinacy,” while woman is given the role of “necessity.” Women bear the function of reproduction, and therefore constitute the necessity for the species to persist into existence. Women also challenge man, either positively or negatively, in the sense that man desires women, and therefore her view of him is important. Man, however, is given the role of building society and actualizing the true essence of humankind as a rational and thinking being.

In its semantic usage, “man” denotes one of the two genders that categorize human beings into biological sexes, relating to their basic roles in the process of reproduction. However, in a philosophical sense, “Man” is a synonym for the “rational” being. Darwinian evolution rates sexual reproduction over self-reproduction as a higher form of development. In other words, self-reproduction is a trait of more primal organisms, such as plants or bacteria, while sexual reproduction is characteristic of more complex animals, including mammals and humans.

Man is a rational being because he can access the universal transmission of “Reason” occurring naturally in the universe. This means that Reason exists outside of man and is not necessarily dependent on him. However, man is dependent on Reason in order to conceptualize his essence. The difference between man and all other known living beings is that he is a “rational animal,” meaning that he is aware of his own consciousness, and this consciousness grants him a higher awareness than that of all other animals. Reason exists in the world beyond him, of which he is only a part of the whole.

2.19 Marx – “Imagine ‘man to be man”

When a human produces a piece of “art” or technology, they create something “universal” because anyone else with the same rational capabilities as the creator can use, understand, and appreciate the product. The product of art shapes the person, and not just the other way around. While the person moulds the art, they are also moulded by it. Marx says: imagine humans possess “human” senses; he explains that “art” requires developed capabilities for its appropriation:

“Assume man to be man, and his relationship to the world to be a human one: then you can exchange love only for love, trust for trust, etc. If you want to enjoy art, you must be an artistically cultivated person; if you want to exercise influence over other people, you must be a person with a stimulating and encouraging effect on others. Every one of your relations to man and nature must be a specific expression, corresponding to the object of your will, of your real individual life. If you love without evoking love in return—that is, if your loving as loving does not produce reciprocal love; if through a living expression of yourself as a loving person you do not make yourself a beloved one, then your love is impotent—a misfortune.” (Marx, The Power of Money)

Most contemporary thinkers often misinterpret the above quote as a case for “socialism” because they assume that in a utopian society, “love is only exchanged for love” and “truth for truth” (or trust for trust), and therefore there would be no need for monetary value, like “money,” to govern proper economic relations. However, this interpretation may be far from the truth because it misses the core point of the argument. If “love is used to invoke love,” this means that, regardless of whether money is used as a system for governing transactions, the actual “value” being exchanged is intrinsic to the transaction itself.

In other words, the “monetary” value (the representation of measure) cannot truly hold the value because “value” is defined by its use-value (utility)—i.e., the function it performs determines where the value lies. The function of money is to facilitate the exchange of things of value. Therefore, if you simply exchange money for money, it becomes a “Ponzi” scheme, which leads to inflation. The actual value transferred by money is inherently tied to what it enables or performs for the consumer.

Money is often confused with being the product of value, when in fact, money is simply a means of trading the true value, which is the product (or production) that impacts people’s lives. The system of money is merely quantitative, and the question is not about its necessity because it is clear that some form of money system is necessary for the proper functioning of a society that is not governed by love—a realistic, non-utopian society. However, the essence of “relations of love” lies in the fact that, in the end, man is left with one thing true if all else is false: the value of his relations. The quality of his relations determines the true wealth of his existence because it constitutes the entire content of his life.

Marx explains that “relations of mutual recognition” must be both reciprocal and mutual. Similarly, artistic work must be recognized mutually and reciprocally. Both, however, require developed capabilities for their recognition—“realization”—and therefore, actualization. Developed capabilities include rational and ethical aspects, or what Aristotle outlines as virtues, of which there are two types: moral and intellectual virtues. For instance, a “universally developed individual” possesses both phronesis (practical knowledge) and episteme (theoretical knowledge).

2.20 Divine Intervention

The idea that God is a distinct entity from the environment that manipulates it for man, and that man is another identity manipulated by God—like in the Abrahamic stories where man is an individual who undergoes a series of divine tests—has the right idea in the sense that the environment is being manipulated. However, it is wrong in the sense that it assumes this manipulation is done by an entity distinct from the particular. The particular, in fact, is a universal, or its identity can be particularized, even if it is a set of particulars or the culmination of many particulars. In that case, it is still a particular identity.

Even if we say “distinct variables” constitute different parts of the same nature, this still does not explain how they are different. The “difference” arises from the interaction between the universal and the particular that makes them distinct, not because they are inherently distinct before interacting. The universal is not an identity such as “God is the universal” because He governs all things, since this is merely another abstraction.

The universal is distinct from a single particular by exerting a superior force over it, but it is the force for particulars without itself being a particular. This constitutes its peculiarity. This idea can be understood in the following way: the individual operates within the environment by performing actions that change it. These changes have certain effects that return to the individual.

The manipulations of the environment by the individual take on an independent force against the individual. This is called the universal. However, the universal is not merely a byproduct of the individual’s actions and their effects. These actions, at one point in time, were universally determined—they were conceived—and this forms the specific moment in the individual’s life.

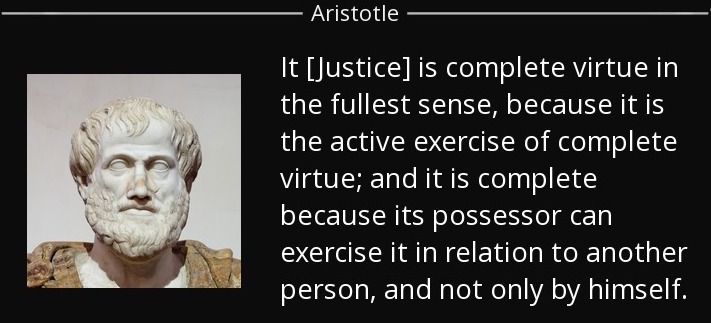

2.21 “Justice” is the “complete virtue”

The individual makes use of the universal in the form of “virtues” when partaking in “justice,” which, according to Aristotle, is the practice of “complete virtue […] in relation to our neighbor” (Nicomachean Ethics, Book V). According to Aristotle, “justice” is the ultimate virtue because it requires and “encompasses all virtues for its actualization.” These developed capabilities—such as “an eye for beauty of form,” as well as the experience of such beauty—are the true “currency” exchanged in the “relation of mutual recognition.”

Aristotle engages in an extensive discussion about the concept of “justice” and what it might entail. Ultimately, he defines justice as “complete virtue” because it involves the practice of one’s own virtues in relation to other people. The implementation of virtue in relation to others constitutes justice as “complete” because it requires the exercise of both theoretical knowledge (episteme) and practical knowledge (techne). The ultimate aim of justice is to provide the “Good” not only to one’s own self, but also to share that with others. As with technology, its universal application benefits others, and this would be an exercise of justice in the classical sense.

Thrasymachus – Justice is the benefit for the Powerful

The Ancient Greek Thrasymachus offers an inverse definition of justice in his debate with Socrates, arguing that justice is solely for the advantage of the stronger. Socrates counters this by asserting that justice is not merely for the benefit of the strong. In theory, those who are the strongest can define justice (make the laws) in ways that benefit themselves, as they hold all the power, and the weaker must obey. It might seem that justice would be complete if it aligns with what the powerful decree. However, the universal definition of justice is an “ideal” of the “Good,” like a Form, and therefore the Truth must be independent of those who define it. Different people in power may have different definitions of justice over time, and thus, the idea that justice is solely defined by the strong cannot sustain a proper universal definition of the concept. To properly define “justice,” we must include its ideal form.

Producing in “the true realm of freedom” is an exercise of praxis, i.e., an end-in-itself activity. “Free time,” in such an activity, “is wealth itself” (Winslow Marx, 1971, p. 257). More time is made for the enjoyment of “free activities” in “the true realm of freedom,” such as spending more time playing beautiful music, rather than making the instruments required for such music. “The realm of necessity,” i.e., instrumental activity or poiesis, is consistent with “the true realm of freedom” insofar as both are expressions of the “universal.” Producing in “the realm of necessity” is “universal” since it also requires developed ethical and rational capabilities to create the necessary ‘means’ for the ‘end’—for example, in order to play the best piano music, one requires the best piano.

(In other notes 1.1)

2.22 Objective Idealism — “Every philosophy is an idealism”

If this inquiry is to be labeled under a philosophical trope, it can be attributed to “objective idealism.” The reader is urged to refrain from placing preconceived notions on what objective idealism—a somewhat confused philosophical topic—might constitute. It is confused in the same way that the term “metaphysics” is often misunderstood, because the term “idealism” is typically thought to concern abstract ideas devoid of any concreteness. This inquiry aims to establish, throughout its scope, that the latter claim is far from the truth. In fact, every science is idealistic because the supposed subject matter is taken to constitute the ultimate basis for reality.

When the notion of “idealism” is distinguished from “realism” — or rather, what we take to be ‘reality’ — it assumes a fictitious and unattainable meaning. However, idealism is synonymous with reality because it ascribes the “goal” or “telos” (i.e., purpose) that a real process is heading toward. In this way, every science is idealistic because the supposed subject matter is taken to constitute the ultimate basis for reality.

Every science assumes a substance from which the world is made, and on which reality is based. For example, scientific materialism takes the notion of “matter” as constituting the absolute substance of the universe. Hegel explains:

Science of Logic, Remark 2: Idealism, § 316

“The proposition that the finite is ideal [ideell] constitutes idealism. The idealism of philosophy consists in nothing else than recognizing that the finite has no veritable being. *Every philosophy is essentially an idealism, or at least has idealism as its principle, and the question then is only how far this principle is actually carried out. This is as true of philosophy as of religion; for religion equally does not recognize finitude as a veritable being, as something ultimate and absolute, or as something underived, uncreated, eternal. Consequently, the opposition between idealistic and realistic philosophy has no significance. A philosophy that ascribed veritable, ultimate, and absolute being to finite existence as such would not deserve the name of philosophy; the principles of ancient or modern philosophies—water, matter, or atoms—are thoughts, universals, ideal entities, not things as they immediately present themselves to us, that is, in their sensuous individuality—not even the water of Thales. For although this is also empirical water, it is at the same time also the *in-itself* or essence of all other things, and these other things are not self-subsistent or grounded in themselves, but are posited by, are derived from, another, from water; that is, they are ideal entities.”

“Now, above we have named the principle or the universal the ideal (and even more, must the Notion, the Idea, and spirit be so named); and then again, we have described individual, sensuous things as ideal in principle, or in their Notion, still more in spirit, that is, as sublated; here we must note, in passing, this twofold aspect, which showed itself in connection with the infinite, namely that, on the one hand, the ideal is concrete, veritable being, and on the other hand, the moments of this concrete being are no less ideal—are sublated in it; but in fact, what is, is only the one concrete whole, from which the moments are inseparable.”

Objective idealism is not necessarily ideas devoid of content, or “fancies” lacking in matter, but rather, the general sense of idealism concerns the influence of “mind” on the nature of reality. Objective idealism is appropriate for this inquiry because the principle of “Reason” is contended to be the essential substance for what our organs of sensation conceive as the “material” world.

2.23 Berkeley – False Idealism

Berkeley is often said to have provided the first Modern account of idealism. However, his attempt at idealism is confused—an account that I would categorize as an example of what idealism is not.

Reduction to Absurdity

Berkeley sought to show that “sense-data” cannot exist apart from the mind. In doing so, he assumed that because the mind is part of the world, the world is, in some sense, a “part” of the mind. In other words, the world is fundamentally mental. The problem with this presupposition is not the claim that the ‘world is fundamentally mental’, but rather that the “mental” is defined entirely as “sense-data.” This type of reasoning is known as a reductio ad absurdum (also called argumentum ad absurdum), or an argument that reduces the opposing view to absurdity.

In logic, reducing an argument to absurdity is considered a fallacy because:

a) it does not allow the argument to stand on its own, and

b) it diverts attention from a possible flaw in one argument by highlighting a possible flaw in the opposite argument.

The reductio ad absurdum argument attempts to establish a claim by showing that the opposite scenario would lead to absurdity or contradiction. In other words, if we accept the opposing view, it would result in absurdity, so my view must be true and not absurd. Essentially, this type of reasoning suggests that just because the other position is false, the opposite must therefore be true. In legal terms, this could be considered “defamation of character”—misrepresenting an opposing argument in such a way that it appears ridiculous or the consequences of that position seem absurd.

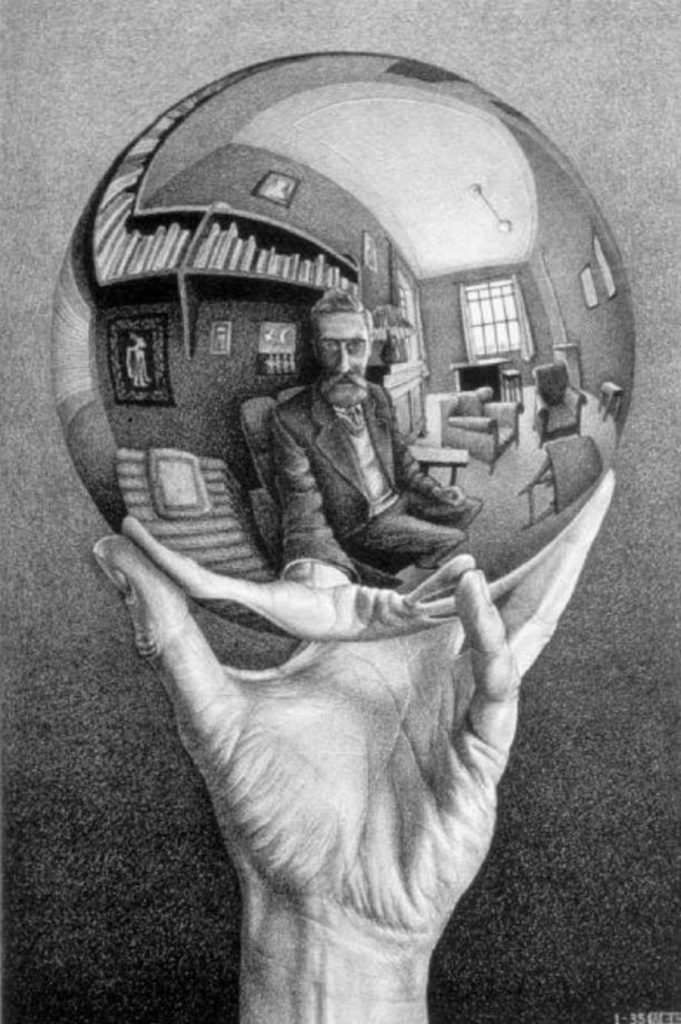

2.24 Sense-Data

The claim, “The world is nothing else but sense-data”, is misinformed. The notion of sense-data simply refers to the information about the world that we derive from our sensory organs. Berkeley explains how the mind is part of the world; in other words, the world is received by the mind through the organs of sensation as sense-data. However, Berkeley fails to explain how the world is part of the mind. In other words, how is the world governed by reason? What is the abstract element in the world? The abstract element of the world cannot be sense-data because sense-data is the concrete element of the mind. Thus, we are still left without an explanation of how the mind constitutes the abstract element in the world.

The distinction between the concrete and the abstract is central to our discussion of sense-data. For example, the modern formulation of quantum science relies on the primary principle that the physical world is indivisible from the abstract element within it, namely, the observer. The “observer phenomenon” in quantum science constitutes the limit of the concrete and sets the initial conditions for what we identify as the abstract aspect of reality.

Berkeley concludes that the world is “mental” because it is presented by sense-data. If the senses conceive a world we call “material” and sense-data cannot exist apart from the mind, then, by virtue of their conception, matter is actually mental. However, this stipulation does nothing to explain the rational or logical structures within the object. In Berkeley’s view, matter is mental simply because he insists that the nature of the object is only sensible.

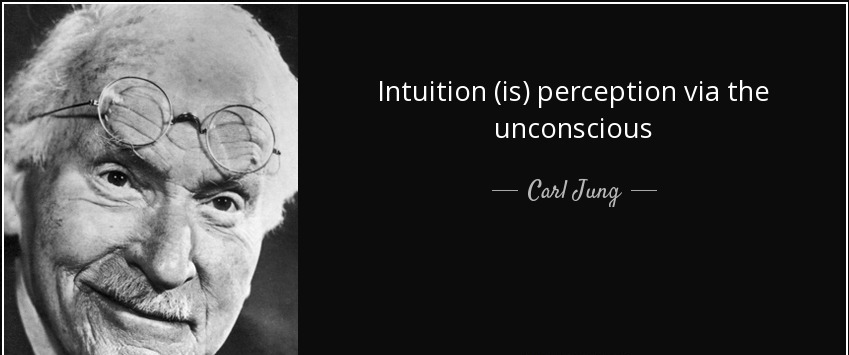

Berkeley’s position is empiricism disguised as idealism. Carl Jung questions the possibility of “complete” knowledge derived from sense-data by pointing out the limits of the senses.

Carl Jung – Sensation

There is no smell, sight, or sound if there is no smelling, seeing, or hearing. Carl Jung famously says:

“Man, as we realize if we reflect for a moment, never perceives anything fully or comprehends anything completely. He can see, hear, touch, and taste, but how far he sees, how well he hears, what his touch tells him, and what he tastes depend upon the number and quality of his senses. These limit his perception of the world around him. By using scientific instruments, he can partly compensate for the deficiencies of his senses. For example, he can extend the range of his vision with binoculars or of his hearing with electrical amplification. But the most elaborate apparatus cannot do more than bring distant or small objects within range of his eyes or make faint sounds more audible. No matter what instruments he uses, at some point he reaches the edge of certainty, beyond which conscious knowledge cannot pass.”

— C.G. Jung, Man and His Symbols

The entire field of quantum physics rests on the principle that the physical world (the concrete world of sense-data), at the subatomic level, is influenced, altered, and affected by rational (mental) operations originating from the self-determination of the observer. In other words, while thoughts on a macroscopic scale may not have a physical force capable of altering the material composition of what is received by the mind as sense-data, at the infinitesimally small atomic scale, rational operations may possess the kind of physical influence (such as vibrations, or whatever you may call it) that can physically alter material compositions. This is why the observer can never be fully separated from any phenomenon, either directly or indirectly.

The observer plays a passive role in watching the physical phenomena without directly interacting with it; this is the indirect role of the observer. On a quantum level (atomic), however, the observer somehow possesses the capability to directly alter the physical composition of the phenomenon by merely observing it. The latter phenomenon is becoming evident at a macroscopic scale with the emergence of technology.

2.25 “Idealistic” Cosmology

Every science is idealistic, for it takes what it aims to prove as constituting the absolute subject-matter of study. For example, physics takes motion as absolute, mathematics takes number as absolute, and philosophy takes reason as absolute. All of these subjects treat their principles as absolute and presuppose them as such.

Especially cosmology, as an ontological science, must answer one fundamental question: From where did everything come from? This is the hardest question to answer, but any cosmology that does not aim to answer this deviates from the task of cosmology—being the science of origin, which is also simultaneously the science of order. The order of the universe is the same question as its origin, and therefore also its Being. Explaining how something is ordered is to explain how it originates.

Certain pragmatic conclusions, like Dewey’s, state that “it does not matter how things came to be; instead, the question is in what way do they already exist.” But now what? What are we going to do with what already exists? This is a wrong approach to cosmology and philosophy in general, in how we approach an understanding of the object. This assumes that things are not in constant change, but rather that things exist as a static result. Process philosophy, however, sees that things are always becoming, and even when things appear to be standing still for a moment, this does not explain what already exists. The absolute is becoming, and not being. How it comes to be is part of its being, they are indistinguishable.

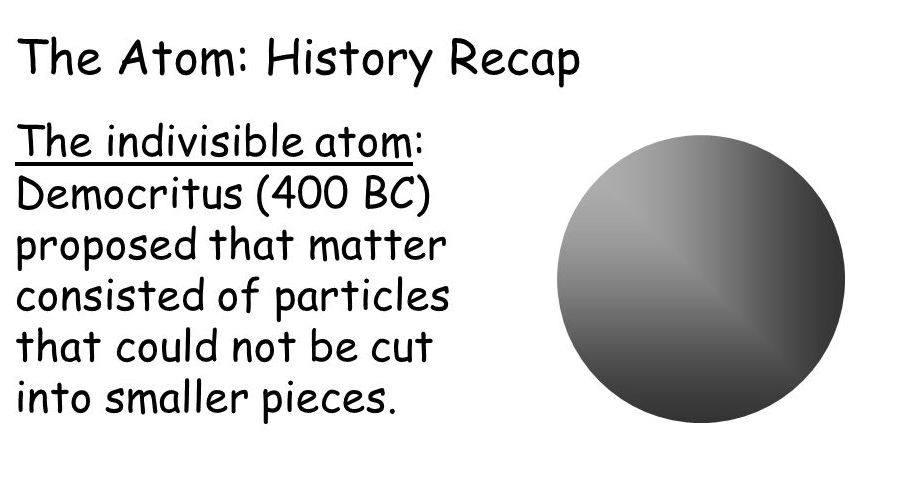

2.26 Idealism in the Atomic theory

The influence of the mind on the status of the basic material blocks that exist can be taken a step further by idealism. For example, in atomic theory, the atomic structure is the more fundamental nature embedded in the “perceivable” objects. However, even if the atom is the more minute nature “inside” the macro objects, atoms are still more general because all matter is “made up” of atoms. The atom is more “abstract” than the material objects we consider “concrete” because atoms are only theoretically tangible.

Atoms are not an “object” in the sense of being a singled-out thing that can be comprehended individually and separately from other things. Rather, they are a relation that forms the gradient of a quality. For example, hydrogen atoms are not a single atom; they are always considered as part of an innumerable scale of atoms that together form a quality—such as light, flammability, chemical properties, etc.

If “truth” is already present and knowledge is what reveals it, then how can truths exist before they are known? The activity of thought—or more precisely, the manner in which you think—constitutes the idea that knowledge and truth are indivisible.

2.27 Fake Modesty

There is a fake “modesty” in which individuals are not trying to “impose” or promote their views; they are simply trying to “understand” the case. They have no opinion on the matter at hand and strive for an “impartial” view. However, this “agnosticism” still promotes a “particular view” as truth. A subjective view of the truth is being presented by the individual, disguised as objective.

When we say “view,” we literally mean a “perspective”—not an opinion, but rather a standpoint from which truth is conceived, a conception of reality, like a position in space from which an object is perceived. However, unlike perceiving an object from a certain position in space, you, the individual, are the particular interplay of events in time. In this way, every person knows the truth, or as Aristotle says, every person “has something true to say,” which means they observe the truth from a certain “angle.” However, the “Truth” is not identical with the individual purporting it.

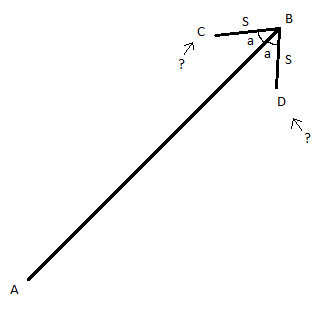

“Angle” of Truth

An “angle” is a specific position, equal to the furthest point on an arrow, derived from the largest area of a diameter, the open area (space) generally disclosing the infinitesimal point. Every person occupies an angle of the truth—that is, the truth is observed in a unique way that no one else can occupy, except for the particular observer occupying it in that moment. The only thing an individual can offer is their view, which does not mean that because it is their “view,” it is by default false. Here, we are saying that views are true in at least pointing out a limited conception of the truth. This is still objective, in that it is a partiality of the truth, like the toenail of a dinosaur—a partial artifact of it.

However, for the same reason, a limited view can be false because it is an abstraction of the truth, an obscurity of the totality. So, we have to step outside the individual truth and look at a more collective compilation of truth—that is, the sum set of individual contributions to the truth. This totality of truth is still subject to the same limitation as an individual truth is, because a “group of truths” is still a particular form of truth, identified as a totality. In that sense, it is received by an individual and, therefore, is an abstraction of the Truth in general. The Truth, ultimately, is not the sum set of conceptions of the truth, but the thing these conceptions are based on, to which they approach as a limit.

Everyone knows their own truth, and there is no confusion about it because it is self-evidently their experience. By this definition, truth is that which exists the most, yet we ask whether there is truth or not, as if we lack something essential.