First updated: 2022.09.22

1.1 Starting Point

The question of where to begin is a peculiar one in metaphysics because the “first philosophy” cannot simply introduce the topic at hand; it must rather make a statement about the concept of “beginning” in general. Intuition naturally seeks to understand the world by eagerly “spilling out” all the ideas within the mind, but a logical system deserving the name of “first science” requires the establishment of a starting point as a foundation for truth.

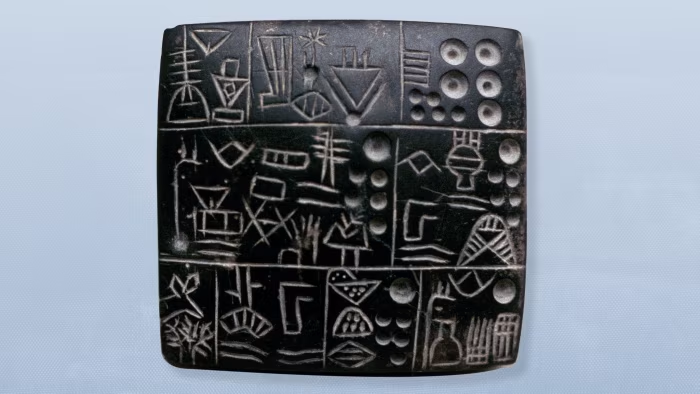

The goal of metaphysics is to formulate a beginning, but it cannot, like other sciences, simply presuppose its subject matter as something already given. This would constitute part of its own content and must be established during the very application of the science. The philosopher begins by reasoning about where to start, taking this very reasoning—about the need for a starting point—as the starting point for the inquiry. In this way, the philosopher delves into the work, asking: what is “reason,” the faculty that inquires into the essential nature of things, specifically the first thing, which is itself, and because it is itself, inquires into each individual expression of itself?

Metaphysics is grounded in the principle that thought takes itself as object, or makes itself its own object. This is perhaps the oldest and most ancient of ideas, and it will constitute the general theme of the inquiry.

1.2 False Introduction

The idea that the introduction is meant to briefly summarize the argument as if the reader is unsure of what they want to read, or if they need convincing so as to read it, or if the topic at hand must appeal to the short attention span and interest of the reader, or as if the reader is meant to gain any real knowledge about the inquiry from the brief abstract; is a recent style of writing, that is NOT relevant in the study of metaphysics.

An introduction obscures the task at hand for the sake of entertainment because instead of focusing on capturing the idea as it “pops-up” in the mind, and “stamp” the conception into a written formate. The introduction provides a false sense of knowledge by appearing to give the “main-point” – as the expression goes “get to the point” – while completely missing the actual point of the thought process; which is going along with the motion of thinking, as it occurs organically in the mind, and then capturing that into a notion, that other people can understand.

The point of thinking is NOT to provide the reader with the “gist” of the idea, but instead, the main point is discovered when the reader engages with the entire thought process itself, i.e., you go through the thought process by laying-out all the possibilities and contradictions of the idea that appear in your mind, when suddenly the point “hits” you, and you realize what your thought is trying to communicate to you. The mind is always revealing truth, the question is whether you are capable of receiving that consciously or unconsciously.

The philosopher must lay-out the entire thought process as it “hits” him in the mind. The idea appears in the mind along with the errors concurred during the investigation of it, and the resolutions to those errors that lead to the discovery of the so-called “point” of the idea, is what the idea reveals, which is “itself”, is the same as the thinker simply participating in The idea. The reader simply participates in the thought process that naturally uncovers itself in his mind.

1.3 No Place to Start?

Philosophy, as a metaphysical project, has no inherent starting point, and therefore, it must first reason about where to begin. However, because metaphysics is devoid of content and has no place to start with, it takes the very reasoning that demands a starting point as the starting point itself.

The philosophy of metaphysics uses the reasoning that asks for a starting place as its very foundation for thought. But this reasoning differs from that of epistemology because, in epistemology, there is already a preconceived set of facts that have been derived and established. The task of epistemology is to reflect upon these pre-established facts, which were derived from more fundamental reasoning in the first place. Epistemology assumes the ontological “facts” about the world (ontology) to be given. Metaphysics, however, does not have this luxury. In the study of metaphysics, thought itself raises the question and then molds the answer from it.

The study of knowledge, in this sense, presupposes knowledge that is to be studied (i.e., in the future tense), but metaphysics seeks to answer a prior question: what is the reasoning capable of deriving knowledge? Ontology precedes the question. If we ask, “What is the nature of knowledge?” as epistemology does, then metaphysics asks, “What is the Being capable of knowledge?” In other words, every fact of the world is fundamentally related to Being. The concept of Being is not simply the nature of the universe to exist, rather than not exist or be absent. Instead, the essence of metaphysics is that the nature of existence is primarily a Being—that is, a living, intelligent entity, such as an observer. Reality, as a feature, is always related to Being. In other words, Being is the fundamental feature of reality; it is always a kind of Being.

1.4 What is ‘Reason’?

What is Reason, in and of itself? There are two ways to answer this question.

- On one hand, we have the common view, primarily from epistemology, that reason is the system of thought—such as logic, mathematics, physics, etc. In this sense, reasoning is the passive activity of applying pre-established concepts to the world, conforming the world to our ideas. However, in order to properly align our understanding with the world, we must first establish a proper worldview, i.e., ontology, about the nature of Being itself.

- On the other hand, Reason as an ontological principle goes beyond our minds and our ability to establish facts about the world. Instead, Reason is understood as a principle inherent in the world itself, meaning that the world is rational, living, and Being. In this view, our understanding is not detached from the world. The common epistemological view is a fallacy because we are not simply external observers receiving knowledge about the world from a detached standpoint. Rather, our mind is the very internal (essential) nature of the universe itself as a Being.

A Being

The universe, as a Being, encompasses our mind and thoughts. To understand how our mind constitutes the essence of the universe as “alive” (or conscious), we must first reverse the assumption that separates us from nature. This can be approached through the following categories: 1) the idea that humans and lifeforms, in general, are “living,” and 2) the assumption that general nature, at large, is “lifeless” and inorganic. The latter proposition is a limited abstraction of the true scale of reality.

It is convenient to assume that life exists only where it aligns closely with our perception of life. However, as our perception of nature extends further and further from the familiar, we observe less and less evidence of life. The limits of our perception in conceiving the universe correspond directly to the limits of our ability to locate other forms of life. As our understanding of the universe becomes more complex and less defined, so too does our capacity to observe life beyond our own planet.

Materialistic

Materialistic ontology assumes that the universe is an inanimate and inorganic reality while simultaneously separating living lifeforms on Earth from the rest of nature, on the grounds that they are considered alive, free, and organic. These views represent flawed ontologies about the nature of Being, which we automatically accept simply because we are taught them from a young age—i.e., the ontology presented to us in school.

Epistemology does not truly address what our systems of thought are based on or even what they are in and of themselves as aspects of nature. Instead, epistemology relies on ontologies, takes their existence for granted, and neglects the need to question their origins. It appears that mathematics, like any empirical science, is an abstraction of something more fundamental, even though it is universally true in and of itself.

For instance, mathematics requires logic, and logic is an aspect of a living observer. Furthermore, mathematics must always be applied to the real world and real objects to achieve completeness; otherwise, it remains hypothetical. Understanding what mathematics represents as an abstraction is the goal of metaphysics.

1.5 Difficultly of Metaphysics

The idea of “Reason,” from a metaphysical point of view, is the very principle to be examined. However, it must not only be examined as an “idea” but also adopted as the central entity of nature—Nature itself revolves around Reason. This means it is a collection of rational conceptions formed into an infinite number of particular sequences, adopted by an infinite potential variety of observers. Of course, all of these—whether the conception, the sequence of a process, or the observer—are aspects of the same phenomenon we are attempting to discuss but always struggle to discern in its true formulation. Anyone who claims to have fully grasped “it” is merely a sophist attempting to “win” an argument, rather than admitting that their own mind exceeds their ability to fully conceive it.

Metaphysics proves to be no easy task, especially given our contemporary mindset in approaching philosophical thinking. Modern pedagogy excludes a critical starting point necessary for understanding the nature of any object. The notion of “Essence” is entirely dismissed, and even ridiculed, when suggested as a causal source for why things happen in the universe rather than not happen.

Essence is the qualitative value of an object, equidistant to its quantitative measure. However, we misconstrue essence as merely a consequence of the object’s function, rather than recognizing that the function of the object originates in actualizing an already predetermined essence.

1.6 Essence

Traditionally, the idea of “essence” is defined by Aristotle as the function of an object. It answers the question of ‘why’ the matter of the object is structured in the way it appears: the shape is related to the function it performs. This offers a somewhat satisfactory understanding of “essence” because it provides a pragmatic answer that can be directly observed. However, when we ask what the essence of “function” itself is—independent of a specific object having an essence—the answer becomes more difficult. The only explanation one can provide is that the reason for anything, or more specifically its function, is a conception.

Essence is a conception because it relates to the “becoming” (coming-into-being) of the object, which is “born” into existence. This means it comes into being doing what it does, and more subtly, it is determined into being by some kind of knower of what it does. The function it performs is the very reason the object came into being instead of remaining nothing. This does not have to resort to God because any living organism is a “knower” of the reasons why objects exist; otherwise, it would not be able to use them. However, the intuition for God always arises as an answer to ultimate questions because there is an aspect of the “final end” of all things—something to which everything ultimately resorts and ends—that comes to mind when we speak of the true essence of all things.

When examining any object, mentioning its “purpose” is often mocked, as if it has no relation to the quantitative measure used to study it. For example, if we discuss the length, width, density, and structure of a chair, pointing out that it has the essence of being “sat on” is dismissed as an obvious fact unrelated to how tall, wide, or thick it is. Yet the quantitative nature of a thing is based on its function: the physical shape of an object is determined by the reason it serves. Still, we are often encouraged to ignore this when discussing an object’s physical stature. For instance, chairs need a base to support a platform for sitting, preferably with some kind of backrest.

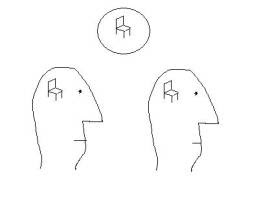

The Form of a “chair”

Aside from providing its general shape, the reason that something serves does NOT necessarily explain the infinite number of ways it can be made. Any object is “formed” in such a way that it is capable of representing the quality it performs. For example, there are chairs of every size, shape, density, and material. The fact that they are all chairs does not explain these differences in their physical properties. However, they are all essentially chairs because of the quality they perform, which is to seat people. Moreover, the function of a chair—to be sat on—does not necessarily explain why some chairs are made out of plastic and others out of steel. It may be for economic reasons (or some other reasons) that one material is chosen over another—for instance, plastic is cheaper than steel—both of which can serve the purpose of being sat on.

Quality is important not just in indicating the function an object performs. For example, the quality of cooking is qualitative because it promotes health, and we say health is good for the continuity of the entity. Quality also addresses the degree to which the material bears varying levels of success in actualizing its intended function. There is a range or spectrum regarding which quality of matter is best suited to perform the function. It is not enough that an object merely performs a function; rather, we must also ask: which object best performs the function when compared to other similar objects?

Even though chairs may differ in quality—something that can also determine their cost (e.g., steel chairs may be of higher quality than plastic chairs, or certain wooden chairs may be the most comfortable)—the general purpose of a chair determines the similar form shared by all chairs. However, this general purpose does not explain the specific differences in material that any object can assume to execute its purpose. This is the argument materialists make: that matter is irrelevant and diverse when executing a function. In reality, matter appears irrelevant only because it is infinitely abundant—that is, there is always “enough” matter to give. When any form comes into being, it always exhibits a material structure that represents its function.

1.7 How to approach Metaphysics

Hegel elaborates;

“But not only the account of scientific method, but even the Notion itself of the science as such belongs to its content, and in fact, constitutes its final result; what logic “is” cannot be stated beforehand, rather does this knowledge of what it is first emerge as the final outcome and consummation of the whole exposition.” (Hegel science of logic 34) <https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/hegel/works/hl/hlintro.htm>

Metaphysics is different because it has a peculiar, and to most, an unorthodox way of writing. The general reader, or someone accustomed to a more “public” style of writing, such as that found in fiction, may sometimes claim that metaphysical works are often obscure because it is difficult to follow the flow of words, and the writing does NOT lead to a “punch line. Asking the question: ”What is the point? This often misses the point, which is simply the act of doing the work, with the point later coming to you—only to propel you forward in search of another point. The conclusion of the thesis is NOT merely handed over by the author in the form of a “distinct” summary, which the reader can skip to, bypassing the body of the work; nor does the body of work necessarily follow from what is sought in the thesis. Moreover, the content that metaphysics deals with, in and of itself, is difficult, independently of the method used to analyze it.

Ontology is supposed to establish a proper foundation for a thesis, which cannot be found at the beginning of the inquiry. In this way, reading an ontological work requires “faith” on the part of the reader, because the idea develops in the mind after the fact, when the thinker stops reading. It is a strange concept to not understand a text while reading it, only to come to understand it afterwards, which seems to defeat the purpose of reading—receiving the information during the act. But this is not the case if the purpose is to elicit reflective thinking, to “download” the thought into the mind, i.e., to plant the seed in the brain. Reading is not done merely to gain information; it also opens up new domains of thought, and therefore new experiences in reality. In other words, using logic to uncover new thoughts is the formula for determining new experiences in reality.

1.8 Principle means Beginning –“thinking things over”

Metaphysics is where thought is introduced to intellectual labour, you do NOT just receive the message, but also “think about it”. Hegel says “thinking things over — in a general way involves the principle (which also means the beginning) of philosophy.” (Encyclopaedia of the Philosophical Sciences (1830) Part One 7)

Principle is defined as a “beginning”; and “Thought” is defined as the “principle” of philosophy. Philosophy does NOT begin with thought in the same way as the other sciences begin with their subject-matter. Hegel elaborates;

17.“It may seem as if philosophy, in order to start on its course, had, like the rest of the sciences, to begin with a subjective presupposition. The sciences postulate their respective objects, such as space, number, or whatever it be; and it might be supposed that philosophy had also to postulate the existence of thought. But the two cases are not exactly parallel. It is by the free act of thought that it occupies a point of view, in which it is for its own self, and thus gives itself an object of its own production. Nor is this all. The very point of view, which originally is taken on its own evidence only, must in the course of the science be converted to a result — the ultimate result in which philosophy returns into itself and reaches the point with which it began. In this manner philosophy exhibits the appearance of a circle which closes with itself, and has no beginning in the same way as the other sciences have. To speak of a beginning of philosophy has a meaning only in relation to a person who proposes to commence the study, and not in relation to the science as science. The same thing may be thus expressed. The notion of science — the notion therefore with which we start — which, for the very reason that it is initial, implies a separation between the thought which is our object, and the subject philosophising which is, as it were, external to the former, must be grasped and comprehended by the science itself. This is in short, the one single aim, action, and goal of philosophy — to arrive at the notion of its notion, and thus secure its return and its satisfaction […]”

(Encyclopaedia of the Philosophical Sciences (1830) Part One 17) https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/hegel/works/sl/slintro.htm

Thought is supposed to be the object of study, independent of the subject. Thought is its own object for study, independent of the person partaking in thought. In other fields, the person is the object of study for thought. For example, in psychoanalysis, thought is used to study the person and their mental behaviors. In philosophy, however, the person is the one studying their thought as if it is an independent phenomenon. Thought is adopted as a universal principle, independent of any particular person partaking in thought.

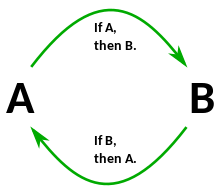

1.9 Circular Reasoning in Inverse Logic

Circular reasoning is the most primal and natural way of the Understanding, Hegel says:

“The very point of view, which originally is taken on its own evidence only, must in the course of science be converted to a result — the ultimate result in which philosophy returns into itself and reaches the point with which it began. In this manner philosophy exhibits the appearance of a circle which closes with itself, and has no beginning in the same way as the other sciences have”.

Philosophy, according to Hegel, exhibits the “appearance” of a “circle” because it must return to the proposition it initially presupposed, with truth at the end. Circular reasoning is defined by the “inverse” proposition. The term “inverse” has a multiplicity of different dimensional applications in the world; for example, the following words are synonyms — reverse, opposite, contrary, and “the other side” — which retain the same difference in meaning, i.e., if one exists, it presupposes the existence of the opposite meaning. Our thinking processes operate in this inverse way. Whenever one thought is imagined, the opposite is presumed as a parallel alteration of it. These alterations (alternatives) are concurring at a rapidly infinitesimal rate, but they are subject to logical order. It is the latter proposition that we are after. To make sense of how the world is apprehended by the mind as inverse alternatives, we can take, for example, the idea that “one can entirely come to understand the world by a set of contradictions.” The world can be categorized as a set of these contradictions, containing variables that are inverse to each other, while at the same time dependent on each other. For example, there is hot and cold, male and female, happiness and sadness, etc. The Truth as a whole can be understood as a series of these inverse contradictions.

The “inverse” supposes that there is first, (1) a position arising from a self-identical point of view, and then second, (2) an “other” that is NOT identical; different and therefore oppositional to the first identity, (3) which itself takes on a separate, and therefore an outside existence from both the self-identical point of view and its other. The first self-identical originator makes a return to itself through the transition into difference that it subsumes in order to self-identify as the same identical principle. This return to itself through the “other” is the essence of “circular reasoning,” and it is the moment wherein thought has form and therefore shape. Thought exhibits the most basic form of a circle because that shape discloses within itself all other shapes (see the squaring the circle paradox).

According to Plato, Form and Thought (Reason) are synonymous and identical because they are, analogously, the intersection between the abstract and the concrete. Plato’s science is practical because for the first time, the abstract becomes concrete when it exhibits “Form,” which is eternal and universal ideas for the mind, or shapes and objects (mimics of those forms) for perception and the senses. Form is the moment where the abstract is made concrete, wherein objects embody ideas.

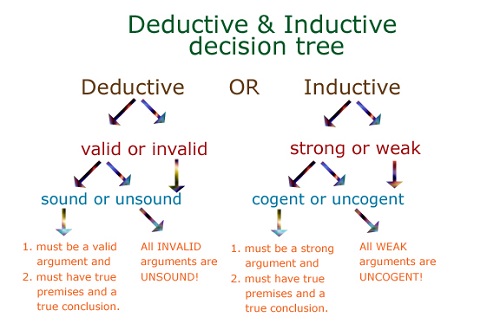

1.10 Circular Reason is NOT a Fallacy

In our ordinary thinking, we label “circular reasoning” as a logical fallacy, not because it diverges from providing true conclusions, but because, as a method, it is considered unpragmatic. Circular reasoning is defined as when the thinker “begins with what they are trying to end with.” However, this can still be valid because it involves the component that, if the premises are true, the conclusions must be true. Our issue with circular reasoning is due to technical reasons. If you begin with the conclusion you are trying to reach, then there is no process that shows how you arrived at that conclusion. The conclusion no longer becomes supported by the premises; it becomes a mere assertion, and an argument cannot rest on an assertion because it depends on demonstration. The power of “demonstration” lies in the fact that, even if something is true, it must be shown how it is so. Therefore, we cannot accept a conclusion—the endpoint—as true without also accepting the process as the source for the result. The process, or in the case of form, the circular reasoning, is the essence of the conclusion. In practical terms, it reconfirms what ‘ought’ to be true.

Circular reasoning is only a problem for communication purposes. However, it is fundamental for thinking because thought cannot begin with anything other than a conclusion; that is all it has. The proof of that conclusion, supported by the premises, is something that comes after, not before. For example, in the modern tradition—whether it be German idealism, English empiricism, etc.—all call the faculty of the “Understanding,” also known as the faculty of judgment, because the first moment of understanding begins with the judgment of whether something exists or not, true or false, wrong or right etc,. The judgment concerning the existence of a thing comes prior to the judgment of whether something is morally good or not. However, the term “judge” carries with it an essential moral implication that cannot be ignored when speaking of the term.

1.11 Inverted Reasoning

Any proposition in logic exhibits a relation that, when inverted, portrays the very contrary side of that thinking. This logical relation is “circular” for a reason: the end-point of one proposition is the beginning for another. Where one ends, the other begins, and the contradictions found at the beginning are the resolutions reached at the end. But look at it from the other way: the contradictions you reach at the end are the resolutions for the beginning of the next claim, because they are the content and material thought uses to work with to make the next propositions.

For example, in our legal system, the concept of “precedent” is essential because future laws are built upon previous conclusions about past problems. In this way, our laws are scientific and logical because they built upon a foundation of truth, rather than simply rediscovering the truth each time as if it needs to be found for the first time. A linear type of thinking proposes a single thought as if it is complete on its own. But this so-called “complete” thought is always made incomplete by its inverse proposition, which actually points out something that it was missing, i.e., the other side of that thinking.

Circular reasoning has a geometric basis, i.e., points occupy opposite places in space so as to complete the length of a line. It will also be the way we write in this work: our language is logic, which is meant to make you ‘think’ about what you are reading, rather than simply receiving some kind of information from it. If you are looking for mere information, you are better suited to reading a newspaper. But if you enjoy the act of thinking for ‘no’ reason—or rather, the reason for its own sake—then continue reading…

1.12 Writing Style

The method of ontology, concerning writing style and philosophical exposition, involves considering philosophers and ideas together in an interwoven way, instead of the more standard method of presenting their views separately and then drawing connections afterward. This interconnected style of writing is naturally dialectical because it involves figuring out and establishing the subject matter, rather than simply analyzing it. The ultimate key to the writing method of ontology is to allow ideas to naturally negate and resolve each other, with the thinker, in this manner, simply officiating the process by channeling it into a communicable system.

Truth is NOT about proving something to someone for some advantage, as is the case in law, but is the mere self-conscious expression of the natural operations of thought as they organically occur in the mind. Metaphysics is the catalogue of the logical spontaneity of thought, arranged into a system that can be communicated.

It has become a recent custom that when writing research, the author ought to identify with their work, as if it is a product made by them and represents their personal point of view. This really has nothing to do with the content of the work and is an irrelevant procedure in an ontological inquiry if the purpose is the experience of pure thought.

1.13 Involuntary Thinking

According to ancient Buddhist traditions, thinking is an involuntary process in nature, much like the growth of trees or the changing of the weather. The voluntary element of thinking lies in the reflective awareness of the natural operations of thought happening in the mind.

Thinking is a natural process, similar to “growing your hair or breathing”; the only difference is that the philosopher strives to communicate what he conceives from this process as honestly and accurately as possible (Alan Watts, Out of Your Mind: Essential Listening, Session 1). A fundamental presupposition in the method of ontology is that “thought” should not be viewed as something personal, so that it can be a proper object of study. What is personal can still be treated as an objective subject-matter for review, much like in psychoanalysis, where personal and subjective experiences are treated as objective phenomena for analysis.

Perception- Mental Fitness

Mental fitness is NOT merely about “focus,” but rather the capacity to sustain consciousness for an extended duration of time. While we might call this “attention span”—the span of your attention—this is NOT exactly true either in accurately defining “mental fitness.” Attention, in this sense, refers simply to the ability to maintain awareness (or observation) of objects through direct perception.

Perception is the ability, through the eye, to reflect images (moments) of reality into the mind. These images are of real objects having a sustained existence outside the eye in space, but they also act as a recollection of a predetermined event in time. What we “see” in space as objects are the residuals of moments happening in time; they are the “residue”, the reflection of the mind outside its own observer.

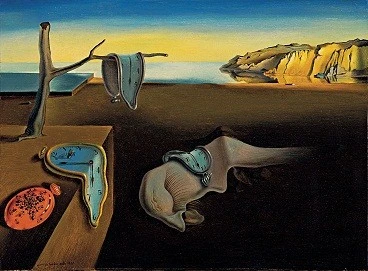

What you “see” has already happened, is enduring, and is simultaneously ending all at once. However, the ordinary mind does NOT perceive the world in this way. Instead, the very act of reflection requires an inversion, which is then inverted again, returning to some original (or predisposed) form. The act of inversion performed by the eye extends the particle state of the moment into a wavelength energy “beam” that undergoes duration in time, embodying those three characteristics mentioned earlier, i.e., simultaneity, instantaneity, and eternity. The wavelength of the moment in time has the beginning, the transition, and end already built into the very fabric of its substance. The mind can only scan this duration by undergoing each moment as if it is one coming after another in a chronological order. The true order however of which, is not determined in the same chronological order that the mind observes the sequence of events in time.

Concentration

The ability to maintain consciousness is an inward capacity for monitoring your own thoughts without losing the essence of their meaning. Mental fitness is defined by this ability, rather than mere focus. When we lose track of consciously apprehending the meaning of our thoughts, we revert to an unconscious state that we mistakenly recognize as “attention span.” In terms of perception, attention is simply the awareness of objects externally occurring outside the observer. However, the perception of objects directly in front of the observer can still remain in an unconscious state, just as the mind can have unconscious thoughts of which the observer is unaware. They are “there”, but you are not aware of them.

Reading an ontological work demands mental fitness—specifically, the ability to concentrate. This is why philosophy, on some level, is a meditation on the natural operations of thought. Concentration, in the philosophical sense, is the act of focusing consciousness on the operations of thought as they naturally occur in the mind. However, this kind of “concentration” is NOT about focusing exclusively on one object to the exclusion of others. Instead, it involves maintaining detachment from thought while still using it, in order to become conscious of it. You use the aspect of thought that does NOT identify with what is being thought about to simply observe your thoughts. This allows you to see how all the naturally distinguished elements fall together into the same conclusion.

1.15 Failed Attention

The “trick” is NOT to adopt a general attitude of detachment from thoughts. There are two ways to be impartial towards your own thinking: First, one can be “detached” from their thoughts in order to observe them “objectively” and NOT be personally influenced by them. Second, one can be impartial by “ignoring” their own thoughts because they are afraid of the truth that might emerge if they confront their own mind. Our goal is to reconcile these two extremes by understanding their relationship, which is NOT about taking an emotional repose toward your thoughts—meaning NOT reacting to them instinctively without calculation—but rather facing the harsh realities of truth by proactively determining them with a desired outcome for the observer. Ultimately, this is the method of taking “control” over your thoughts and shifting from pre-determined patterns to conscious determination.

Most people fail to maintain attention after a certain period when reading philosophical works by Aristotle or Hegel because their thoughts wander, causing them to lose track of the reading. This happens due to the inability to detach the mind from the act of reading. The natural opinions that arise from “thinking” pull the thinker “somewhere else,” away from understanding the essence of the content. However, this “somewhere else” the thinking takes the reader should be seen as an achievement, not merely a deviation—so long as the individual goes far enough to “find” themselves resulting in an “idea.” The truth within philosophical content should ultimately bring the reader “back” to the point they were trying to reach when they first sought the content.

1.16 “ignorance is bliss”

“Ignorance is Bliss”

The “truth” can sometimes set the reader into a mindset where they cannot manage what spontaneously arises in the mind. They cannot “let it go” and become fixated on their own thinking, without resolving meaning from their thoughts. In this way, the observer becomes “stuck” in a perpetual state of trying to understand, without ever arriving at actual understanding. They enjoy searching for “it” without ever truly finding “it.”

The “thoughts” that occur in the mind are NOT arbitrary, nor are they “just thoughts” in the sense that they lack relevance to reality. On the contrary, thoughts are always attempting to communicate something important to the observer; that is their function. It is only when the observer does NOT properly reason through those thoughts or misapprehends them that they form a feedback loop, continuing to repeat themselves in the mind. The thoughts do NOT let go of the observer—they “hunt” him, because he fails to “face” them. He purposefully remains ignorant in order to avoid confronting the TRUTH of his reality.

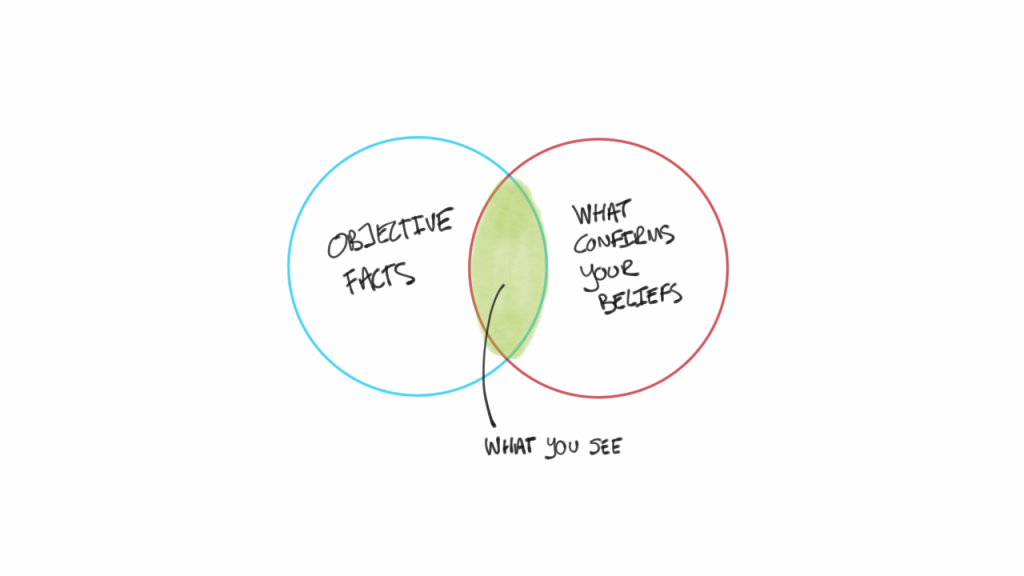

Ignorance is NOT accidental. You are “ignorant” NOT just because you lack the ability to know, but because there is an active component to ignorance—like actively ignoring something you know to be present, such as looking the other way. We do this all the time when it comes to the full truth of reality. Our evolutionary “adapted” modes of perception are geared towards ignorance of most of reality, focusing only on a certain resolution of it.

Carl Jung famously writes in his book Modern Man in Search of a Soul (paraphrase):

“We all can see, smell, hear, etc., but how far we can see, how much we can smell, to what extent we can hear, is the question concerning the limit of our senses.”

We constantly “look the other way” from our thinking, but deep down, we know that if we confront our minds, we will come to “know” the very facts we are avoiding. Human beings have a natural proclivity toward willful ignorance. However, the realities of nature do NOT allow this “ignorance [as] bliss” state of mind to persist for long. The realities of nature forcefully drag man out of his slumber, much like the man in Plato’s Allegory of the Cave, into the light of Reason. Initially, this light burns the eyes, but once the senses become accustomed, the mind perceives a higher reality than the one previously known. Man evolves forward with this new insight, whether he likes it or not. The question then becomes: What will he do with it?

1.17 ‘A Complex’ – Reoccurring Dream Theory

In psychoanalysis, the individual may experience the same dream repeating over and over again for years. In the case of recurring dreams, the observer has failed to properly “reason” (think), indicating that there are unresolved issues in waking life that the person cannot solve. The dream, therefore, manifests as a “complex”; or, philosophically, a “complexity,” which represents an illogical set of relations in the mind—a bundle of contradictions. It’s like a collection of tangled strings that the thinker has not been able to untangle, either due to a lack of mental fitness or virtue. The individual cannot confront this abstract complexity and attempt to resolve it by unraveling it into a solution; in other words, they fail to understand how the contradiction itself may contain the resolution.

When we learn to solve “problems” in school, such as a mathematical equation, we are strengthening the mind’s capacity to untangle logical contradictions that naturally arise in daily life, with real ethical consequences. Reality differs from a mathematical equation in that it has concrete consequences that affect the well-being of the subject. However, it resembles a mathematical equation because it requires a logical framework and resolution to achieve a certain result—i.e., a conclusion that follows from the premises. This process is not merely a mechanism of logic, but rather the mechanism through which potential events in time become real, concrete moments for the observer, shaping the remaining duration of existence.

If “complexes” are left unchecked, the individual may develop a fixation on certain repetitive thoughts, leading to anxiety disorders. In contemporary society, we often view mental disorders as arbitrary, meaning we do not always know their cause. However, it has only been recently that mental illness has been discovered to have strong links to physiological effects, such as stress-induced illnesses. This will be explored further in a later section, but it points to the connection between thought and physical consequences. These effects are not random; they are acquired and serve a specific purpose for the individual.

1.18 It’s (“NOT”)“just in your head”

The old claim that “it’s just in your head,” suggesting that something is not “real”, overlooks the real problems that the mind communicates with the individual. The individual ought to listen to their mind, as if what is being thought has the same efficacy as reality—just as if an event were happening right before their eyes. However, it is more difficult than simply “listening” to the mind because the individual must also resolve their thoughts, and they can only do so if they are mentally fit. In other words, they must be able to reason (think) well. The mind presents logical challenges to the individual, and these challenges are identical to the life scenarios the person is dealing with at any given moment. The abstract logic that the individual witnesses in their mind at any given moment will serve as the very abstract blueprint for a real-life event they will experience at some point.

How well the observer reasons will determine their access to new (novelty) information that naturally arises when properly resolving a logical problem. Only when “I” begin to engage with the activity, do its aspects start to be revealed. The proper way to resolve a logical problem is NOT by possessing technical skill—i.e., the ability to memorize and re-assimilate rules or equations—but rather by addressing the ethical issues that logic presents to the individual. It is in their choices about what is “ethical” or “not ethical” that the success of their resolution is determined.

What is ethical is considered objective, not relative, because even though there are infinite possibilities, the choice of one over the other determines a real, observable, and apprehensible moment. Relativity is akin to a ‘potential’ state, while objectivity pertains to a ‘real’ one. However, the categories of what is “real” as opposed to “ideal” fluctuate depending on the relationship with the observer.

The idea takes center stage, and all the importance will go to the idea that naturally arises in the mind. The reader, however, must anticipate the spontaneity of ideas that emerge and deal with them case by case, seeing them for what they are—as part of the same spontaneity.

Reading without “Truth”

Reading without the “idea” that supports it becomes laborious, without the reward of the truth that is supposed to come at the end of the reading. The truth should be presented at the onset, so that the duration of the reading serves to prove the principle. The truth should NOT be used to entice the reader. It should NOT be like a “carrot dangling in front” of the reader, but should be fed to them in order to nourish their future course of action.

When the student is left uncertain as to whether there is truth or not, this causes the thinker to feel discouraged and tired, often concluding that either they are unable to understand the content, or that the content itself is lacking. Typically, academic types claim that the content is lacking because they are encouraged to be “critical thinkers” and cannot admit—especially in an environment where their intelligence is esteemed—that their own intelligence may be lacking. For example, academics often dismiss the truth of Hegel based solely on his writing style, and this reveals the difference between shallow thinkers, who cannot move beyond the language barrier, and deeper thinkers, who access meaning through the language they encounter. As a general rule: the thinker most despised by mainstream academics is likely the one worth reading.

1.19 Doubt

Reason is NOT only the topic of this inquiry, but also the principle upon which all other concepts are built. In other words, Reason is the first and foremost essential substance that contains and discloses both reality and the mind. Reason is not something contained in the mind, but rather, the mind is a discrete measure, a particular manifestation of Reason.

There is a sense of an “incomplete feeling” that the reader will naturally encounter when engaging with Metaphysics, or any other form of art for that matter. As Alan Watts says:

“Every poet, every artist, feels when he gets to the end of his work, that there is something absolutely essential that was left out.” He later goes on to say, “The whole art of poetry is to say what cannot be said.”

This ineptitude is NOT necessarily due to the subject matter lacking in content, nor is it simply the incapacity of the reader as a limited thinker. The “incomplete” feeling that the reader always experiences—no matter how much information they receive—is, in fact, a natural manifestation of doubt. If the mind is a piece of spacetime, then doubt is a discrete measure within that continuity.

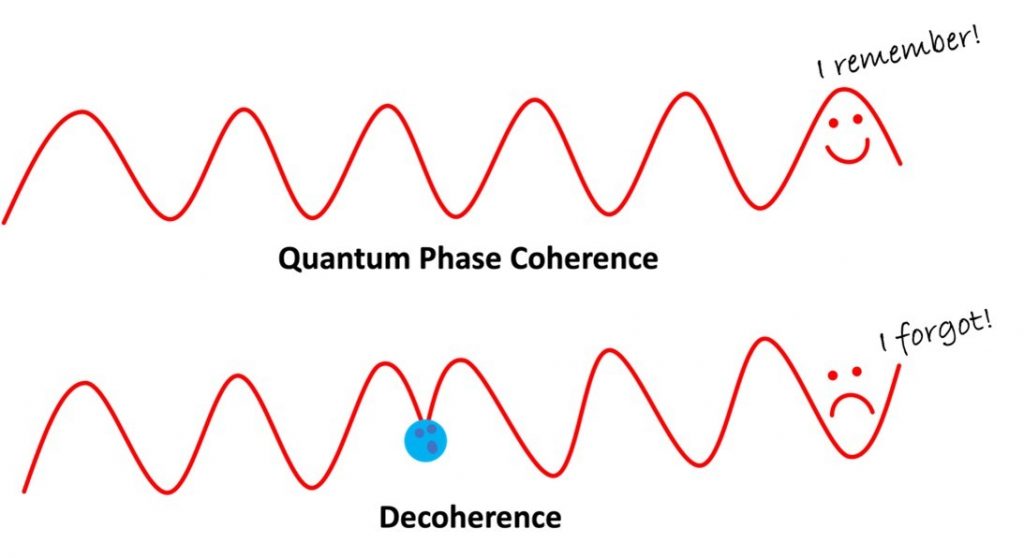

Doubt is a “discontinuity” between one thought and another. The thinker interprets this discontinuity as a lack of thought, an ineptitude of thought, or thought that is lacking. The “ineptitude” of thought occurs when the thinker is unconscious of the operations happening in their own mind. They “miss” the point, or rather, they did not “catch the hint.” When you become unconscious of the moments unfolding in your mind, this is actually a distraction caused by a disruption in the wavelength frequency between your mind and the world it operates within.

The consciousness of the thinker becomes “tired” of reasoning because Reason is always ongoing, eternal—like Plato’s Forms in nature—while consciousness itself is a fluctuating field, going “in” and “out” of rationality. When consciousness is in tune with Reason, we call it awareness or realization; when it is “out,” we call it unconsciousness.

1.20 Definition of Quantum “doubt”:

When the thinker forgets the events occurring in the mind and later realizes them, this interval is what we call “doubt.” The idea of doubt is not merely an uncertainty or indecision that the individual mind experiences. Doubt is built into the very nature of reality itself. The discrete measure, or pause, in the individual mind distinguishes one idea from another.

The interval between unconscious and conscious realization of the ideas in the mind is actually the transition from one moment to the next in time. Just as one object is separate from another in space, they do not merge into each other, creating a disfiguration that cannot be distinguished. Similarly, there are separations between moments in time that correspond to the distinctions between ideas in the mind. The Mind and spacetime outside the mind share in the same continuum at the basic subatomic, or fundamental level of reality.

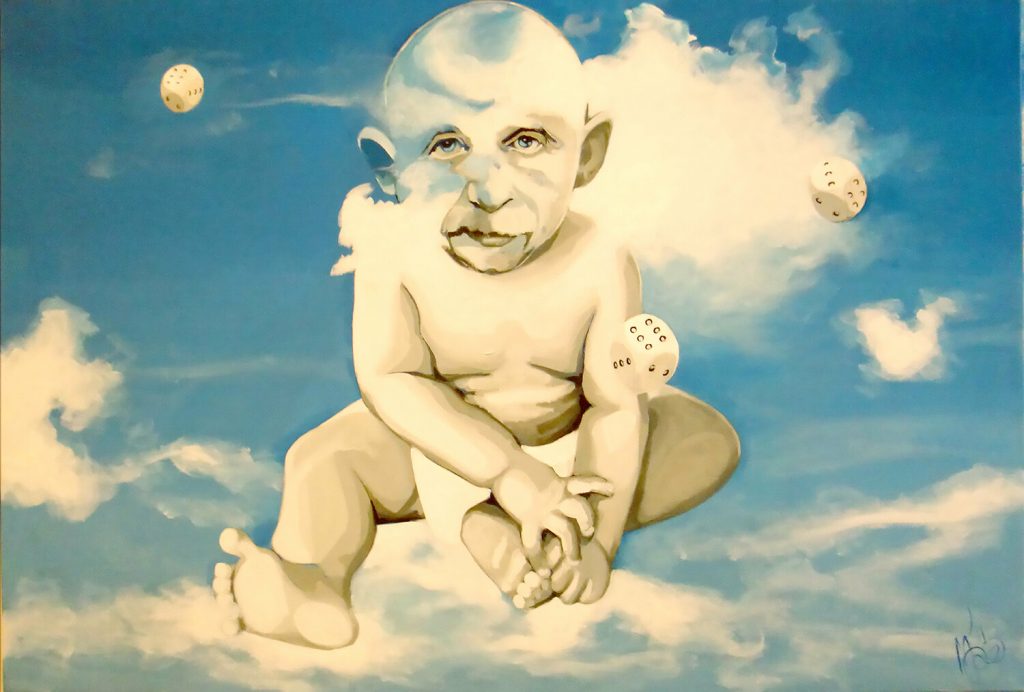

1.21 a “quanta”

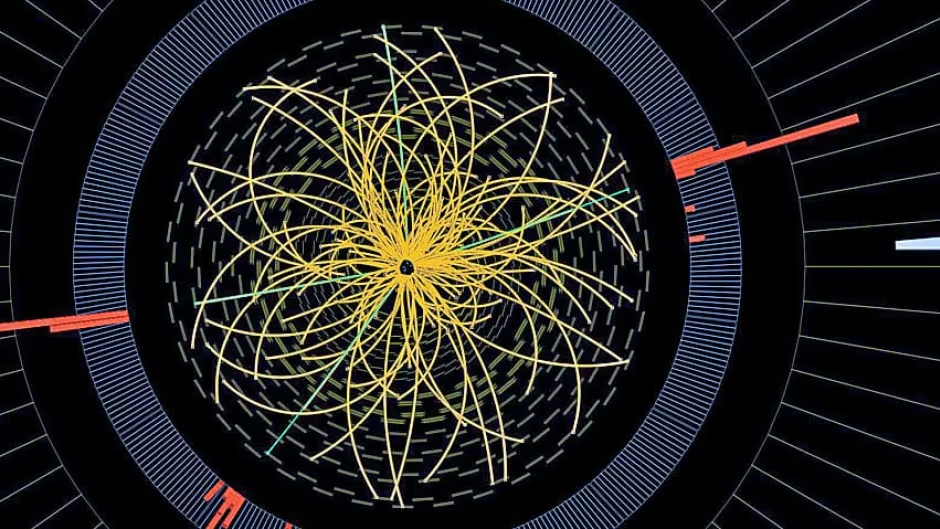

In our modern scientific accounts, quantum mechanics describes the basic energy state of the universe in terms of a “quanta”—a discrete point of energy “flickering” in and out of Being at a rapid pace, such that it is impossible to predict its position on a quantum field. Quantum fields can be characterized as — “invisible fields of information that exist independently of space and time.”— We are certain that quantum fields are real for one unambiguous reason: they carry energy. This discrete energy state—a “packet of energy”—whose instantaneous emergence into being is also simultaneously its exit into non-being (nothing), characterizes the physical side of the abstract notion of Reason in the human mind, known as Thought. In other words, it is what thought is. Light is the basic behaviour of matter at the most abstract level.

When there is a lack of interest or “distraction”, this is NOT a disconnect between one thought and another. The assumption is that thoughts must follow a certain order based on a narrative that the individual presupposes about their own identity. In more scientific terms, thoughts must be structured in a specific logical order. Logic does not only mean that an order must follow a particular structure; the precondition for logic is that all the possibilities of an argument must be laid out and revealed. As long as the individual is not discouraged by this hurdle, they can proceed to the thoughts that fill the void of doubt with content, and piece these contents together to form a general understanding.

1.22 How to Approach Reading Quantum Philosophy

The first and foremost principle to adopt when reading philosophy is that there is “no” topic. In other words, “Nothing can be talked about.” The phrase “Nothing can be talked about adequately” is interesting because it is a double negative. On one hand, it positively asserts that the concept of “nothing” can be talked about adequately—that it could be discussed correctly; in other words, nothing is a subject matter that can be addressed. On the other hand, the term “nothing” negatively affirms that no single thing on its own can be talked about adequately—that every subject matter is inherently incomplete (or lacking).

- This does NOT mean that you cannot talk about anything. In fact, you can talk about everything, including “nothing”—which is neither of them nor anything at all. However, any topic is incomplete because there is always the idea of “nothing” in contradiction to it.

- It also does NOT mean that you must first talk about everything in order to talk about anything. In its applicable meaning, “nothing” is NOT absolute; it is a positive affirmation, meaning that no subject can be talked about completely, or that partial knowledge cannot be talked about adequately. Comprehensive knowledge does NOT need to address all concepts, but only the fundamental ones, which ultimately presuppose everything that follows.

1.23 Structure

As for the structure of reading an ontological work, we are accustomed to reading from the top of the page and moving down to the bottom. However, we might achieve the same result if we began at the bottom and read upward, and then returned to the bottom. This is an experiment one should try, not a rule. It mirrors how we glance over a piece of work before we begin to read it in depth. The key to understanding metaphysical writing involves informal reading habits. This means one of two things:

First, meditation in the realm of reading requires that the mind should not only focus on the act of reading itself, but also pay attention to the mood and attitude that thought takes in reaction to what is being read. There is a danger here that the mind may wander off into thoughts unrelated to the reading, causing the meaning of the content to become lost or unclear. The continuity between thought and reading is a conception external to both, maintaining a concentration on each doing its own thing, while being in relation to one another.

Second, philosophical writings should be read in an abrupt manner. When the reader feels they are no longer absorbing the content, or when the content begins to seem disjointed, they should stop reading and look out into their environment, meditating on the thoughts that naturally occur after reading.

Worrying about losing track should indicate that the reader has already lost track, and a brief stoppage is required simply to see if what they remember from the reading presents itself naturally in the mind. This is why this inquiry is divided into many subsections—not only because the aim is to talk specifically about certain topics, but also to help the reader maintain checkpoints throughout the journey of thought, and to represent the abrupt nature of thinking accurately in the form of a conception.

1.24 Headlines — Headings over each subsection

The reader is discouraged from relying on the heading of each subsection as if it should indicate the topic under discussion. The heading of each section is NOT the topic itself, but rather a general sense or a “keyword” in the content that captures the reader’s attention, helping them maintain some checkpoints throughout the inquiry.

There is no special topic to be discussed in metaphysics other than Being, which encompasses all topics. Moreover, there is no set path to follow in a true ontological work, but only a general sense of thought-flow. Therefore, the reader can start from anywhere and still arrive at the same result. This will become clearer as the reader discovers the ultimate point (or purpose) of ontology.

The reader may “think” (or assume) that their understanding misrepresents what they have read, but this so-called misrepresentation is actually a form of paraphrasing the essential idea by the reader, in relation to how it is written by the author.

1.25 Confirmation bias

There is the possibility of “confirmation bias,” where the reader believes that what they have read confirms an already existing belief or idea. However, this is precisely where the continuity between what you read and what you think merges into a contradiction, which is unraveled by understanding.

The reader is encouraged to trust their thoughts that bring doubt to the discussion and should listen to these thoughts, as they are natural logical responses to the content being received.

The reader should adopt the position of an observer, meditating on what is being read in relation to what occurs naturally in their thought as a response to the reading. Often, the reader believes that because they do not understand the text, the content must be beyond their mental capacity, and therefore, they cannot critique what they do not understand.

Many times, philosophers complicate the matter at hand because they deal with complex issues. However, just because the issue is complicated does not mean the articulation of it must also be difficult. Often, clarity is sacrificed on the premise that the topic is inherently complex.

When you read a text that is not succinct, it may indicate that the thinker themselves is struggling with the topic they are articulating. The written word should never be seen as complete or whole, but rather as an abstraction of a thought process, captured as a timeless expression of words. The complexity of the writing style reflects the real struggle the thinker is having with the idea in their mind. This dialectic will naturally become more evident and clearer as the discussion continues.

The end… (Find next section)