Modern Introspective

Section 11 (first updated. 12.27. 2020)

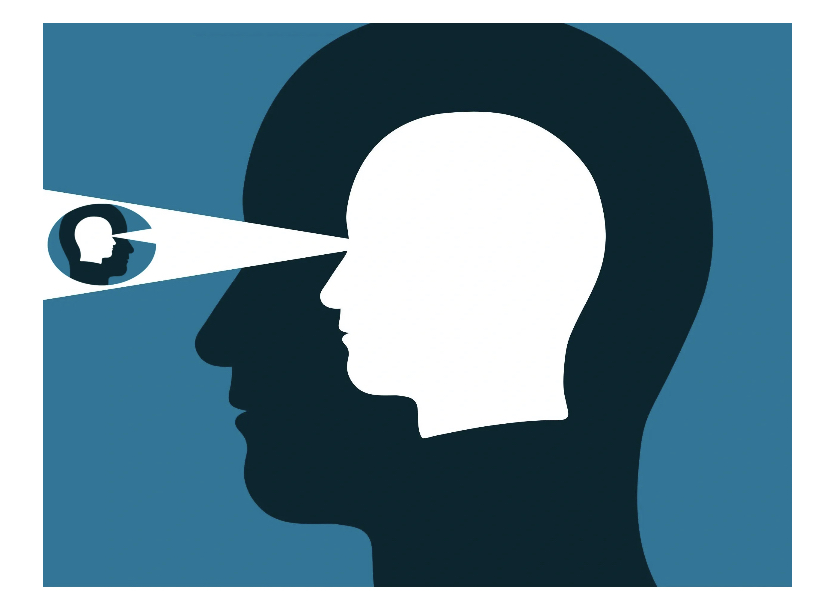

Intuition is the self perceiving itself from a moment other than the present.

The term a priori does not mean that “experience need not follow,” or that knowledge is derived without any experience whatsoever. Rather, the notion of “without experience” means that such knowledge is not determined bydirect experience, but rather, determines direct experience. When considering how experience relates to the order of a priori conception and experience, we must ask: In what order is the experience revoked or anticipated by the observer as an a priori conception? In other words, we question the causal relationship between experience and concept—which precedes which? This is a variation of the classic causality dilemma: Which comes first, the chicken or the egg?

For example, an a priori truth might be expressed as: “You do not need to break a hand to know that it is a bad thing.”However, this claim presupposes that, at some point, a hand has been broken, whether by oneself or another. Even if no hand is broken, we understand the qualitative distinction between good and bad. Here, ethics becomes foundational to knowledge. If the hand functions naturally, and breaking it causes it to function unnaturally—contrary to its intended purpose—then this alteration can be deemed bad, without requiring the actual experience of it¹.

Knowledge that is a priori is true independently of experiences as they are situated in time. Yet a disparity arises between thought and experience, because sometimes an experience triggers a thought, while at other times, a thought occurs independently of any corresponding experience.

The notion of time itself involves this disparity: thoughts may arise without regard to the linearity of temporal sequence. For example, one might reflect on the past while in the present, or infer the future based on a memory of the past². In this way, thinking resists temporal closure—it transcends discrete moments.

Footnotes:

- Kant discusses this principle in The Critique of Pure Reason, where he distinguishes between synthetic a priori judgments and empirical experience. The ethical example parallels his idea that certain judgments are valid prior to and independently of experience, yet they may still presuppose a historical or empirical framework.

- Augustine, in Confessions (Book XI), famously wrestles with this paradox: “What then is time? If no one asks me, I know what it is. If I wish to explain it to him who asks, I do not know.” The mind’s ability to reflect on the past and anticipate the future while situated in the present illustrates the mind’s transcendence of sequential temporality.

Nature Ethics: Health

A Priori of Matter

Value is the measure of the a priori—that is, knowledge prior to experience. Whether or not someone undergoes an experience does not alter the way a thing exists in and of itself¹.

The ancient Greeks associated nature with the standard of ethics². A thing is considered “good” when it acts in accordance with its nature, and “bad” when it deviates from that nature. Nature, therefore, provides the foundation for an ethical standard because it relates directly to the purpose of a thing.

To act contrary to one’s purpose is to do bad; to actualize one’s purpose is to do good. Purpose is the idea that sets something into motion in the first place. It is the reason for a thing’s existence. Whether that purpose manifests as an experience, a function, or a task is a more refined question³.

Pessimism contends that it was a mistake to come into existence at all, and that the appropriate attitude should be to resent or reject the reason that brought one into being. However, this outlook cannot escape the reality of Being itself. Whether one resents existence or not, the fact remains that one already exists. Furthermore, the reason why one dislikes their existence is, in many cases, entirely dependent on the self.

Often, unhappiness stems from unhealthiness—from doing what one ought not to do, and neglecting what one ought to do. Few would argue that health is overrated. Even those who disregard health often wish they had it. Likewise, individuals who despise life still maintain health at least to the extent necessary to subsist. Even those with suicidal ideation generally continue to eat, sleep, groom, and function until the moment they decide to act. This reveals that ideation requires duration in the present—a space in which fantasies or projected futures can be entertained before action is taken. This paradox implies that health is a natural value of good, implicitly preserved even by those who claim not to value life⁴.

Footnotes

- This is an echo of Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason, where he distinguishes between the noumenon (thing-in-itself) and the phenomenon (thing-as-experienced). The existence of a thing in itself is not contingent on subjective experience.

- See Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics, Book I, where he grounds the concept of the “good” in the fulfillment of function (ergon) according to nature.

- Aristotle again provides insight in Physics and Metaphysics, where telos (end or purpose) is essential to understanding the being of a thing. A thing’s essence includes its final cause.

- Philosophers such as Schopenhauer and Cioran have argued that life is inherently negative or burdensome. Yet even within their pessimism, there remains a paradox: the will to end life affirms the intensity of one’s awareness and continued engagement with it. This is closely tied to Freud’s concept of the death drive (Todestrieb) which paradoxically coexists with the preservation of the body until the very act of destruction.

Element

The Meaning of “Element” and Its Ontological Implications

The term “element” carries an interesting two-fold meaning. First, an element can refer to a part or aspect of something abstract. As one may observe, many of our conceptual terms exhibit this quality—they describe components of something abstract or conceptual. Second, element refers to an essential characteristic, and this is the basis upon which we relate it to nature—for example, a natural element like water or air. A synthesis of these two definitions suggests that nature itself is inherently related to something abstract. In this sense, the term element serves to unifyabstraction and essential natural substance into the same conceptual framework¹.

According to modern empirical standards, it is a well-established fact that water, air, and other classical natural elements are not the fundamental constituents of the universe. Their periodic structure reveals that they are composed of more primary elements—such as hydrogen and helium—which are both more abundant and presumed to constitute the majority of the known universe².

However, empirical science continues to employ an ancient method—namely, the adaptation of a particular or peculiar fact as the basis for making ontological claims. For example, when asked what the universe is made of, scientific materialism often asserts that the universe is mostly made out of hydrogen. This quantitative fact is then used to support an ontological thesis: that the universe is fundamentally material. Yet, when confronted with the mental or rational dimension—that is, the subject observing the phenomenon—scientific discourse tends to reduce this mental aspect to a material category, rather than giving it independent ontological status³.

To say that the universe is made out of hydrogen is, in principle, no more ontologically definitive than the ancient claim that the universe is made out of air. The only distinction lies in empirical specificity, not in ontological principle. While factually incorrect by modern chemical standards, the ancient idea is still essentially true in a broader metaphysical sense: “air” was understood as a general principle of life and motion, just as “hydrogen” today is viewed as the substratum of material formation. The element air is scarce in the cosmic scale because it is a very specific and differentiated kind of gas—whereas hydrogen, the simplest and most abundant gas, represents a more general and indeterminate concept of gaseous substance⁴.

Dark matter and Energy

In modern science, it is assumed that hydrogen is the most abundant element because it is observed throughout all known regions of the universe—particularly in stars. However, quantum science introduces a conceptually more abundant and more fundamental component than any element on the periodic table, namely what is known as dark matter.

The majority of the unknown universe is believed to be composed of dark matter, while the known universe—that is, the observable portion—consists primarily of hydrogen, helium, and the subsequent elements. On Earth, for instance, hydrogen and oxygen are more abundant than they are in most other parts of the known universe.

Thus, the extent to which our reality is composed of known versus unknown elements depends largely on the limits of our observational reach. Where we look, we find greater concentrations of certain elements—hydrogen in stars, oxygen in planetary atmospheres. But where we have not looked, or cannot yet observe directly, is likely composed of something more mysterious, such as dark matter and ultimately dark energy.

These unknown substances are not directly observable but are inferred by their gravitational effects on visible matter. It is a logical assumption, grounded in the principle of cosmic equilibrium, that for matter to exist, there must be an inverse—namely antimatter—to preserve the balance of existence. In this view, reality consists not only of what is materially present but also of what is necessary in order for material presence to be possible at all.

Footnotes

- Aristotle’s Metaphysics (Book V) discusses the concept of element (stoicheion) as both the simplest part of a composite and as something that cannot be broken down further. This dual nature of “element” as abstract and essential informs both metaphysical and physical thinking.

- In cosmology, it is generally accepted that hydrogen constitutes roughly 75% of the baryonic mass of the universe, followed by helium at around 24%. See: Carroll, S. (2010). From Eternity to Here: The Quest for the Ultimate Theory of Time.

- This is a key critique from idealist and phenomenological traditions. For example, Edmund Husserl argued in The Crisis of European Sciences that science “abandons the lifeworld,” reducing conscious experience to physical processes and overlooking the very subjectivity that gives rise to meaning and observation.

- The Presocratic philosopher Anaximenes held that “air” was the fundamental substance (archê) of all things, due to its ability to transform into other elements through processes of rarefaction and condensation. Modern reduction of air to a specific mixture of gases parallels the shift from symbolic metaphysics to chemical materialism, yet the function of “element” as grounding principle remains consistent.

Milesian Principle

The Ontological Foundations of Modern Science and Its Pre-Socratic Origins

The contemporary ontological stance of modern science is comparable to the development of empiricism during the Milesian school. It is arguable that empiricism began in the Pre-Socratic era. During this period in ancient Greek philosophy, the dominant ontological predisposition was that the universe is purely material. This view, associated with the Milesian school, represents one of the oldest known positions in Western metaphysical thought¹.

However, this materialist viewpoint was not the final conclusion of Pre-Socratic philosophy, which evolved significantly before culminating in the thought of Aristotle. At the early stage, there was no Anaxagoras or Heraclitus, and the universe was still conceived as being derived from one single material element—whether water, air, or fire—serving as the underlying substratum of all things².

Naturally, what followed was a critical development: the conclusion that mind (nous) or reason is the essential governing substance of the universe. This shift occurred as philosophers like Anaxagoras and Heraclitus recognized the redundancy of one material element over another. No matter which substance is proposed—fire, air, or water—it can always be replaced by another with equal validity. This highlighted the limitations of proposing a single material element as the ontological ground of all things.

The flaw in this approach is not merely that each material element provides only limited knowledge about a reality far greater than it; rather, each requires something beyond itself to explain existence. For example, fire presupposes the presence of air or fuel to exist. Thus, saying that fire is the first principle (archê) also implies that air or water could equally be considered first principles, as each provides its own explanatory framework for the composition of nature³.

It is important to recognize that Pre-Socratic terms like fire, air, and water do not correspond precisely to our modern chemical understanding of elements. In contemporary science, elements are highly specific, chemically-definedcompounds relevant to biological life and derived through empirical observation. In contrast, the Pre-Socratic elements were qualitative metaphysical principles, abstracted from perceptual experience, yet not reducible to empirical data alone⁴.

As Hegel famously remarked, Thales is the “first man” because he identified the first element—or, more precisely, he identified the first element he perceived, namely water⁵. His selection was based on what was most abundant and visually apparent. Although Thales’ cosmology is often dismissed today for being inconsistent with our current scientific worldview, this does not render it untrue in a philosophical sense. In fact, Thales’ abstraction of water as the primordial substance reveals a deep insight into the nature of objects and Being in the universe.

Footnotes

G.W.F. Hegel in Lectures on the History of Philosophy praised Thales for beginning the movement of philosophy by abstracting a universal principle from particular experience. Thales’ use of “water” was both literal and symbolic.

The Milesian school (including Thales, Anaximander, and Anaximenes) sought the archê or first principle of all things in a material element. This materialist orientation marks the early stages of Greek natural philosophy.

See Anaximenes’ claim that all things are composed of air through processes of rarefaction and condensation, and Heraclitus’ claim that fire is the underlying principle, symbolizing flux and transformation.

This criticism is in line with Aristotle’s rejection of material monism in Metaphysics, where he proposes a more complex causal framework including formal, final, and efficient causes in addition to material cause.

Pre-Socratic use of the elements was often symbolic or qualitative rather than quantitative. For instance, firerepresented change, water represented continuity and life. See G.S. Kirk & J.E. Raven, The Presocratic Philosophers.

Thales cosmology- ‘flat land on vast water’

Water as Arche: Reconsidering Thales’ Cosmology

Thales believed that water is the essence of all matter because he conceived of earth (as an element) as a flat disk floating upon a vast sea. To properly engage with this abstraction, we must suspend our modern cosmological assumptions and attempt to inhabit the ancient mindset—to see the world as the early thinker saw it. This does not mean that Thales’ view was merely subjective, nor that reality is determined by the particular mind that conceives it. Rather, his abstraction strives to articulate a truth about Being that transcends individual perception.

If we contemplate Thales’ abstraction more deeply, we find that water represents more than a material substrate—it carries an essence, a productive principle that gives rise to certain qualities. If we reduce water to just a material medium and ignore the essential outcomes that arise from it (e.g., growth, motion, life), then we find no meaningful distinction between it and void, space, or dark matter. These all share in the general concept of matter, but differ by essence. If we recognize matter as a substratum common to all, then essences are what distinguish one element from another: water carries the essence of life, while void, darkness, or emptiness carry the essence of death. These different essences are not incidental—they are ontological characteristics of the material substratum itself¹.

Thus, to speak of water floating in the void is to describe the division between life and death—the potential for life emerging from a backdrop of non-being. For the ancients, the world was not a void, but a place of life. Thales’ famous claim that “water stands under all things” was not simply a physical hypothesis—it was an ontological claim that life, growth, and change presuppose a living medium².

In modern thought, water is regarded as one principle among many in nature, such that the universe could still exist without it. But this overlooks the essential role that water plays in the developmental logic of the cosmos. If we view the universe as an empty void in which events happen accidentally and without reason, then water may seem unnecessary. But if we instead affirm that the universe is a domain of ordered events governed by causes and directed processes, then water becomes absolutely essential—not just for biological life as we know it, but for the very possibility of development³.

To say that water is an arche (ἀρχή)—a first principle—means that we must not conceptualize it as simply layered onto space, like an object placed within a container. It is not that 1) space comes first, then 2) water exists within it, and then 3) earth floats on top of the water. Rather, space itself is disclosed through water, such that without water, space would lack meaning. If water is as essential as space—or even prior to it—then space becomes a kind of cover or shadow that veils the generative potential of water as a source of life⁴.

A cosmological structure that influenced much of ancient ontology can be summarized as follows:

- Water is the first essential layer of the universe; it is the ground in which even space is contained, and it represents the substance of life.

- Space conceals water as darkness, as the absence of direct perception or the limit of observation—the unknown that surrounds the known. For example, like the ocean at night, you cannot distinguish below from above; in the darkness, the water and the sky seem to merge into a single unity for perception.

- Earth, as both element and planet, is disclosed on top of water; the life it bears is only possible because of the essential nature of water. The Earth—specifically, the land—both stands above and rests beneath the water, such that water functions as a kind of space for land. Just as space today serves as the platform for planets, water serves as the platform for land.

This view reverses the modern assumption that space contains all elements; instead, it proposes that the essential element contains space, and not the other way around⁵. It could be that where we see dark space today, Thales saw that darkness as underlain by water—that the entire universe, where we now observe darkness, is actually filled with or sustained by water. This view only makes sense if we shift our ontological perspective: instead of seeing the universe as a lifeless arena, we must view it as a place of life. For Thales—and indeed for many of the Pre-Socratic philosophers—the universe was understood as a living organism, not an inanimate collection of objects.

Footnotes

- In ancient cosmology, elements were understood as essences, not just material building blocks. See Empedocles’ four elements and their relation to philia (love) and neikos (strife) in establishing a dynamic system of reality. Also see Anaximander’s idea of the apeiron as the boundless source.

- Thales is recorded by Aristotle in Metaphysics I.3 as holding that “everything is water.” While this is often interpreted materially, the symbolic and metaphysical reading suggests water is a principle of life and cohesion, not simply fluidity.

- This is closely related to Aristotle’s concept of teleology—that nature does nothing in vain and that natural processes aim toward ends (telos). Water, in this view, is not accidental but instrumental to nature’s function.

- The inversion of space and matter challenges Newtonian metaphysics, which sees space as an empty container. This alternative resembles Leibniz’s relational view, in which space is the order of coexistences and is dependent upon substance.

- This idea foreshadows Neoplatonic metaphysics, where the One or Source gives rise to multiplicity, and space is derivative rather than primary. See Plotinus, Enneads V.1.

Arche – the First principle

From Element to Reason: The Pre-Socratic Path to Universal Substance

The Pre-Socratic philosophers each began their inquiries by positing a single, observable element—perceived through the senses—as the fundamental substance (arche) from which all things arise. The problem with asserting any one such element as the ultimate cause of all things is that it invites the issue of infinite regress: if water, for instance, is claimed as the fundamental principle, why not air, or fire, or any other observable phenomenon? To designate a substance as fundamental requires that it be unique—not merely another thing among others, but rather that upon which everything else depends. It must be, in other words, the first and the source of all multiplicity.

This philosophical trajectory began with Thales, who identified water as the arche, followed by Anaximander, who posited the apeiron (the infinite or indefinite), and Anaximenes, who chose air, understood as capable of self-motion(and thus soul-like). Later, thinkers like Heraclitus proposed fire as the principle of change, while Anaxagoras introduced nous (mind) as a cosmic ordering principle. Eventually, this progression culminated in the idea of universal reason (logos) as the most fundamental substance. In this conception, every object can ultimately be reduced to its abstract form or idea, making reason the only true, underlying essence of all things.

The Pre-Socratics also grappled with the paradox of the One and the Many. Numerically, the paradox seems insoluble: the One cannot be singular, for every “one” implies the possibility of another like it. Conversely, the Many is nothing more than a collection of single Ones, and thus is itself, paradoxically, another One. However, this paradox finds resolution in qualitative rather than quantitative terms: the One can be understood as a shared quality, a common essence that appears in multiple forms. The Many are thus qualitative instantiations of a single archetype.

This historical progression among the Pre-Socratics shows that each philosopher replaced the prior’s arche with another more abstract and inclusive one—each aiming to identify a substance that possessed characteristics the previous did not. This dialectical development eventually led to the idea of reason as the “purest” or most universal substance, since it is that by which and through which all other substances are understood and ordered.

This leads to a deeper philosophical question: Whose mind governs the world? The idea of God is one response—a move from general principle to a more personal or intentional agency. Yet the characterization of God often remains vague or undefined. The answer may not lie in any particular mind, but rather in mind as such, or reason in general, as that which structures reality. The divine, in this sense, is not an anthropomorphic being, but universal reason itself.

The thinkers of the Milesian School were significant not only for their metaphysical inquiries but also for grounding empirical observations in universal claims—a foundational gesture in the development of the scientific method. They did not merely speculate, but abstracted universality from particular perceptual experiences.

As Immanuel Kant later observed in the Critique of Pure Reason:

“A new light must have dawned in the mind of the first man (whoever he may have been) who demonstrated the properties of the isosceles triangle. For it did not occur to him that he must discover what is contained in that figure by merely thinking it, or by merely inspecting its image. Instead, he realized that he must produce the properties of the figure, as it were, according to a rule, and he must derive them from the concepts that he himself had placed in the figure in accordance with its concept—a priori and with apodictic certainty.”¹

Kant’s reflection underscores the pivotal realization: true knowledge arises not merely from passive observation but from active, rational construction. It is this act of reason—projecting order, structure, and form—that defines both the Pre-Socratic quest and the subsequent unfolding of Western philosophy.

Footnotes

- Immanuel Kant, Critique of Pure Reason, trans. Paul Guyer and Allen W. Wood (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), A712/B740.

A priori:

Kant, Thought, and the Reality of the A Priori

What Kant means by “a priori” relates to the way reason is brought into the mind as thoughts. The mind experiences the concept of reason not as an abstraction devoid of content, but as real thoughts and ideas. These are not merely hypothetical or speculative possibilities. In other words, a theory is not simply an abstract or imaginary concept; rather, it expresses the actual phenomenon it is about. Thoughts are concrete events, occurring within the mind, even if they are received unconsciously.

Only with the recognition that human beings are self-conscious, and not merely conscious, did ideas begin to be regarded as “hypothetical” in a pejorative sense—as somehow less real than physical phenomena. But what we call real must be defined as that which has concrete effects on the experience of the mind. From this, we gain a clearer understanding of what thoughts are—but the question remains: How do thoughts appear in the mind?

Thoughts appear in the mind in two ways:

- First, thoughts arise from direct contact with objects. The mind represents the idea of an object it is immediately perceiving. This is what we call knowledge derived from experience, or empirical knowledge. The idea in the mind corresponds to an external object, and there is a kind of match between the phenomenon and the thought that represents it. In this way, both are united in the act of observation; they share a common reality through the observer, who discloses both the object and the idea of the object.¹

- Second, thoughts may arise that do not match experience—in fact, they may contradict it. This is where Kant introduces the notion of a priori knowledge, challenging the empiricist claim that all knowledge is derived from sensory experience.² For Kant, a priori does not mean that thought arises completely independent of experience in the sense of ignoring it. Rather, he means that thought has a structure or form that can anticipate or condition experience. In other words, experience can reveal one thing, while thought about that experience may indicate another. Thought and experience do not always coincide. This disjunction is what makes a priori knowledge both necessary and possible.

If all knowledge were derived from experience, then why do thoughts arise in the mind that seem to contradict what is being experienced in the present moment? Often, the thoughts we entertain do not match the current experiential context. One might argue that an earlier experience causes a later thought, and while this is plausible, it avoids the deeper implication: this disconnect between thought and experience is precisely what we mean by a priori. It is knowledge not derived from any particular experience, but structurally prior to it. It is what allows the mind to represent, compare, or even challenge experience through its own inner capacity.³

Footnotes:

- Plato makes a similar point in the Theaetetus, where knowledge is defined as “justified true belief”—involving the harmony between belief (thought) and truth (reality). See: Plato, Theaetetus, 201d–210d.

- See: Immanuel Kant, Critique of Pure Reason, trans. Paul Guyer and Allen W. Wood (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), B1–B2. Kant writes: “There can be no doubt that all our knowledge begins with experience. But…though all our knowledge begins with experience, it does not follow that it all arises out of experience.”

- Kant distinguishes a priori judgments (independent of experience) from a posteriori (dependent on experience). He also introduces the concept of synthetic a priori judgments, which extend knowledge but are not derived empirically. Ibid., B15–B17.

Knowledge before Experience

The A Priori, Empiricism, and the Indeterminacy of Thought

A priori knowledge challenges the very notion of what it means for knowledge to be derived from experience. If, from the same experience, an external fact yields a certain kind of result, yet internally induces thoughts that do not result directly from that experience—and may even contradict it—then it becomes clear that thought is not always a mere reaction to sensory data. This contradiction undermines the empiricist assumption that the mind is always and only reactive to sense stimuli.

Typically, we assume thoughts follow sense impressions. Yet sometimes, as in dreams or waking intuitions, thoughts seem to predict future experiences. These thoughts may be vague, intuitive, or imprecise, yet they point forward, appearing anticipatory rather than reactive. This very indeterminacy—the openness of thought to what may come—is what allows thought to move ahead of experience.

Empiricism constrains “experience” to a set of observable, measurable conditions, governed by axioms and hypotheses designed to yield testable conclusions. It seeks certainty and clarity, and in doing so, treats speculative thinking as something to be disciplined—redirected or corrected—by empirical precision. Even if this yields truth in a narrow sense, it does not explain the source of thought itself. Where does the capacity for speculative, intuitive, or predictive thinking come from in the first place?

Empirical facts can be highly accurate, but only because they limit the scope of thought—reducing the full range of mental possibility to a constrained set of conditions. They narrow the field of understanding for the sake of reliable results. But this methodology fails to account for the invariable and unconditioned power that gives rise to thought at all.¹

Experience, therefore, can be understood as the narrowing of thought—a reduction of the mind’s limitless potential into a fixed frame for analysis. But this narrowing is a presupposition from thought, not for it. Thoughts often appear to arise spontaneously, in ways disconnected from immediate circumstances. This apparent randomness reveals that thought may reflect indirect aspects of reality—elements not present in direct experience but which nonetheless inform it.

The mind, limited by its finite sensory apparatus, is not directly exposed to the totality of reality. It may be that the mind simply lacks the capacity to conceive of the whole of experience at once. But it is equally possible that thought itself extends beyond experience, disclosing dimensions of reality that remain hidden to the senses but present in reason.²

Footnotes

- Immanuel Kant, Critique of Pure Reason, trans. Paul Guyer and Allen W. Wood (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), B1–B2. Kant distinguishes between the origin of a priori knowledge and the content of experience: while knowledge begins with experience, not all of it arises from experience.

- See G.W.F. Hegel, Phenomenology of Spirit, trans. A.V. Miller (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1977), Preface, §21. Hegel proposes that reason reveals what is not yet apparent in immediate experience, and that thought unfolds what lies implicit in the real.

Future Ideas

A Priori Thought and the Possibility of Experience

A priori thoughts are akin to what Charles Sanders Peirce refers to as “esse in future”—to “be in the future,” that is, ideas that anticipate or foreshadow future conditions or events.¹ For instance, thoughts often arise unbidden in the mind that seem disconnected from current experience, and yet they are troubling enough to prompt reflection. Consider walking down a street or sitting quietly on a bus, when suddenly the idea arises to strike or harm a nearby stranger. The imagined target could be anyone—an old woman, a passerby, a child. The specificity of the scenario does not matter; what matters is the involuntary nature of the thought and its stark contradiction with one’s moral character and conscious intention.

Similarly, while driving a car or riding a bicycle, one might vividly picture a crash or a catastrophic failure, even though nothing in the immediate experience suggests danger. These images come without warning and usually never materialize in reality. Such thoughts are often dismissed as random, hypothetical mental noise—mere intrusions of imagination. But are they truly random?

These so-called “random obstructions of thought” are not merely meaningless byproducts of cognitive function. Rather, they may be expressions of possible routes of potentiality—directions into which the present could unfold. In this view, experience is not a fixed line but a field of branching actualizations, and the observer—through thought—selects, or is drawn toward, one outcome among many.² Thought, then, is not reactive, but constitutive of what we come to experience as real.

However, this “selection” is not always what we would judge to be rational. Sometimes, the most rational outcome by logical standards—say, preserving life or avoiding harm—fails to materialize, and instead an irrational or destructive event becomes actual. Here, what is real is not necessarily rational, at least not from the standpoint of human desire or expectation. This raises a deeper metaphysical question: why do certain irrational outcomes become real, and why does the mind seem to foresee them, even when it has no direct prior experience of them?

In one sense, thoughts about future possibilities are simulations—mental postulations that sketch out what mighthappen. Take the fear of a crash while driving: the thought arises because the possibility is real. But to simulate this possibility, the mind must already possess some template or form of the experience. If the individual has never undergone or witnessed such an event, the question arises: when did they acquire this template?³

Can one experience a thought before it becomes actual in the present? Can one person’s experience be passed downto another without a common genetic link? If we consider that mind is the more fundamental quality shared across members of a species—a universal essence expressed individually—then it becomes plausible to propose that thoughts may be transmitted without physical contact. Just as language, myth, and symbol carry meanings across generations, might thoughts themselves pass between minds through a non-material medium of shared rationality?⁴

In this framework, thought is not merely private nor local. It may belong to a transpersonal reality, wherein each mind is a participant in a shared structure of reason that exceeds the individual. Ideas, then, are not generated by the individual alone, but are received from a collective source that prefigures and exceeds immediate experience.

Footnotes:

- See Charles Sanders Peirce, Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce, Vol. 1–6, ed. Charles Hartshorne and Paul Weiss (Harvard University Press, 1931–35), esp. 1.337–1.341, where Peirce distinguishes “being in future” (esse in futuro) as a mode of real possibility.

- Compare to G.W.F. Hegel’s concept of “actuality” (Wirklichkeit) in Science of Logic, where actuality is not mere existence but the realization of what is rationally determined through internal necessity. See: Hegel, Science of Logic, trans. A.V. Miller (London: Allen & Unwin, 1969), Book 3, Section 2.

- This question mirrors Carl Jung’s concept of the collective unconscious, where inherited archetypes structure thought and imagination without personal experience. See: Carl Jung, The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious, trans. R.F.C. Hull (Princeton University Press, 1981).

- Similar metaphysical ideas can be found in Plato’s Theory of Recollection, where learning is the recollection of knowledge already latent in the soul. See: Plato, Meno, 81d–85b.

Posteriori

Quality, A Priori Knowledge, and the Experience of the Universe

The principle of Quality reveals the internal working of the universe. This inner nature is grasped differently than the objects of empirical experience. Yet this form of insight is often mistakenly identified as a priori knowledge—that is, knowledge presumed to be independent of experience and derived solely from pure reason.

Kant defines this distinction in the Critique of Pure Reason:

“The question is whether there is any knowledge that is thus independent of experience and even of all impressions of the senses. Such knowledge is entitled a priori, and is distinguished from the empirical, which has its sources a posteriori, that is, in experience.”¹

He later distinguishes between pure and mixed a priori knowledge—emphasizing that the former arises entirely from reason, untainted by any empirical data.²

But this classical definition may miss something deeper. The universe is its own knowledge; knowledge is not something separate from the universe, but is rather the very experience of the universe itself. In this sense, knowledge is not a detached observation, but the self-experience of Being. Thus, the concept of “a priori” loses its classical meaning if it is defined as the attainment of knowledge independent from experience. Rather, a priori is better understood as the inner drive, the activity, or the form that a posteriori knowledge takes—the way experience becomes intelligible as it is perceived in the passing moment of lived time.

In this light, a priori is not a fixed category of “non-empirical” truth, but the structural condition by which experience becomes knowable in the first place. It is the motion of experience into form—the dynamic principle that allows quality to emerge through experience.

Footnotes:

- Immanuel Kant, Critique of Pure Reason, trans. Paul Guyer and Allen W. Wood (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), B1–B2.

- Ibid., B3–B4. Kant distinguishes pure a priori knowledge, which contains no empirical component, from impurea priori knowledge, which may still require empirical content for its application.

Principle of Evolution

Mind as Species: The Evolutionary Whole and Its Individual Parts

The mind as an evolutionary organism is not limited to the particular form it assumes through the organs of sensation. In other words, the species is more fundamental than the individual members that comprise it. The species is not an individual organism experiencing the world, but rather a set of experiences shared and related among its members.

This is difficult to conceptualize because the species is only reflected through each of its members. It is the distinct individuals who express the same nature that characterizes the species, and it is precisely this shared nature that groups them together as the same type of being.

The principle of evolution implies that the species (the whole) is more fundamental than any particular organism(the part). The species is the mind—the common nature shared by all living organisms, in whatever form or structure they appear. All species possess mind in some form, but they also possess a particular type of mind, which differentiates one species from another.

Every lifeform possesses a kind of control system—a faculty for directing action and intention. In the case of an organism, this direction is shaped by the species-nature it embodies. All members act in ways that, taken together, fulfill the common functions and ultimate aims of that species. Thus, the species is the totality of nature expressed within each of its individual members.

The mind of the species constitutes the principle of evolution in two respects:

- It explains how evolution involves the generation of new lifeforms, as well as their eventual extinction.

- It accounts for how variations of the same mind—shared across individuals—develop, adapt, and change over time, either advancing or regressing.

The species generates a range of different bodies that perform slightly varied sets of actions and intentions, all oriented toward achieving experiences that, while not identical, are convergent—contributing to some broader pattern of change or progress in future generations.

Footnotes

- Aristotle, Parts of Animals, trans. William Ogle (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1882), I.1. Aristotle observes that the nature of the species is prior to the individual, for the species embodies the form which individuals instantiate.

- Charles Darwin, On the Origin of Species (London: John Murray, 1859), Ch. 3. Darwin notes that species variation is the result of cumulative changes across generations, guided by selection pressures but grounded in a shared hereditary structure.

- Henri Bergson, Creative Evolution, trans. Arthur Mitchell (New York: Henry Holt, 1911), Ch. 2. Bergson’s concept of the élan vital parallels the idea that a living species possesses a unifying impulse or mind, expressed diversely in individuals but oriented toward the same vital aim.

Heredity

The species is the whole implicit in each part.1

We might ask: is it more accurate to speak of the species of mind or the mind of species?

Heredity is a record-keeping system in nature, related to the accumulated experiences of mind.2 The common principle—mind—is not limited to certain organic achievements. It does not belong exclusively to this being or that being; rather, all beings both possess mind and are possessed by mind.3 Mind is also not merely a subjective organ of individuals that allows for experiences; it is more than that. It maintains all experiences across time during the developmental history of a species. There is a general mind innate in each animal—called the unconscious in psychology, or, in biological terms, heredity.4

The concept of heredity suggests that there exists a system in nature that stores information across time, and that this information is encoded in the genetic makeup of organisms undergoing experiences of mind. These experiences teach them new knowledge that is then passed down toward future versions of themselves.5 The information stored in the unconscious dimension of mind constitutes the geometric, genetic, and neurological structures of the biological specimen. The neurology of the brain is based on cultivated and acquired pathways of experience. These pathways are structurally analogous to other organic aggregates in nature—such as fungal mycelia or plant root systems—since they are rooted (pun intended) in nature. Just as individual plants emerge and perish, the species of plant subsists for an indefinite period.6

Neurogenesis occurs when synaptic connections increase the rate of neuronal transmission. As a result, new pathways physically grow outward, like branches on a tree, reaching a spatial limit of their capacity. At the very tip of the nerve is the final event—the most recent developmental moment the species has reached in its evolutionary journey. Yet this so-called present prototype of the species branches into multiple experiential directions in space, each reaching its own peak limit at different points in time. In other words, although the general trend of evolution can be described as upward—that is, generally advancing—the pattern of its progression may be unpredictable. Regressions or downward turns in evolutionary form may still qualify as evolution if they produce novel experiences that yield new knowledge.7

This is analogous to a moral maxim in which even bad actions serve a good function by revealing the nature of the bad itself.8 From such unpredictable patterns we may nevertheless extrapolate an overall upward trend, suggesting improvement over time. However, the specific succession of prototypes may not always exhibit that positive value—or may manifest it in an unbalanced or distorted manner. For instance, a father may be less intellectually developed than his son, or the leap in intellect from one generation to the next may be so extreme that the two seem almost unrelated in dimension of thought. How, then, can one give rise to the other? This difficulty arises because such comparisons are finite and limited in abstraction. They fail to consider the cumulative contribution of all members of a generation that culminates in the apparent leap between father and son. One individual may characterize the species better than another, but the direction in which this occurs is not predetermined or definite.9

Footnotes

This recalls the statistical nature of evolutionary change, where variation across the population—not the direct lineage from father to son—drives adaptation. ↩

This echoes Aristotle’s idea in Metaphysics (Δ, 1017b10–25) that the whole exists potentially in each part by virtue of its form. ↩

Darwinian evolution treats heredity as the transmission of traits, but the analogy to a record-keeping systemsuggests a metaphysical continuity of form beyond purely genetic mechanisms. ↩

The dual phrasing (“possess mind” / “possessed by mind”) reflects a tension between individual agency and the overarching species-mind. ↩

Freud’s concept of the unconscious (Das Unbewusste) parallels the idea that there exists a layer of mental life not reducible to conscious awareness, yet operative in shaping behavior. ↩

This aligns with Lamarckian notions of acquired traits influencing future generations, though in modern biology, epigenetic mechanisms are the closest analog. ↩

See Deleuze & Guattari’s rhizome metaphor in A Thousand Plateaus for a philosophical parallel to the branching analogy. ↩

In this sense, evolutionary “progress” is not strictly teleological but dialectical, with apparent regressions contributing to the overall adaptive knowledge of the species. ↩

Compare with Hegel’s dialectic, where the negative (das Negative) is a necessary moment in the unfolding of the Absolute. ↩

Mind species

Species Memory and Intuition

An individual specimen may not have undergone a certain experience, yet the mind, as a manifestation of the species, has—over evolutionary history—undergone all possible categories of experience.1 This cumulative experiential heritage is ingrained in the very neurological structure innate in each organism of the species.2 Such inherited patterns may account for intuitions about events the individual has never directly experienced, but toward which they have a mental “feeling” or anticipation.

For example, while striking a stranger may be an improbable action in contemporary society, in prehistoric times it may have been a far more common and even adaptive response.3 Conversely, seeking peaceful resolution may have been a later mental assimilation, emerging only after the relative stability of social structures reduced the survival utility of violence.4 This illustrates that ideas can be independent of the individual’s direct experience—not in the sense that experience is unnecessary for thought altogether, but rather that the relation between experience and thought is mediated by processes of causation and entropic ordering over evolutionary timescales.5

The Pragmatic Nature of Mind

The mind is fundamentally pragmatic because it retains past experiences and carries them into the future through the medium of the possible present.6 In future situations, past experiences—now often reappearing as spontaneously generated mental scenarios—serve a pragmatic role: to warn, inform, and shape responses to present circumstances. One can learn from possible scenarios imagined internally, without undergoing them physically in the present, and thus acquire the same information without the cost of direct exposure.

This represents a significant evolutionary advancement: organisms are no longer confined to reacting only to experiences imposed by circumstance, but can instead select experiences to seek or avoid, based on projected possibilities.7 At the same time, the reverse also holds true—the actualization of certain future states is guided by the preexistence of these imagined possibilities.

The Ideal as Temporal Contrast

The past determines the future not merely in the conventional sense—where previous events shape present conditions, which then determine future outcomes—but also in a nonlinear sense, where the past may be placed ahead of the present in a sequence of extensive (rather than purely chronological) order.8 This is possible in an abstract state of mind, where past events serve as enduring standards by which future events are evaluated.

In this function, the past operates as a contrast to the future. Here, “contrast” is used analogously to its meaning in visual art: the deliberate juxtaposition of two elements in opposing ways, such as areas of bright light against areas of darkness.9 In art, contrast creates focal points that structure perception; in time, contrast structures meaning and orientation.

The past, as an ideal, drives future events to unfold in the present. This “ideal” is value-neutral—it can be either positive or negative. Negative events are ideals in the sense that they exemplify what the good is not, while positive events are ideals insofar as they provide a model for what the good is and should be pursued.10

Footnotes

This broader, value-neutral definition of the ideal aligns with certain Aristotelian and Hegelian uses of the term, in which ideals serve as teleological reference points regardless of moral valence. ↩

This claim is related to Carl Jung’s notion of the collective unconscious, which holds that the human mind contains inherited structures of experience beyond personal memory. ↩

Comparative neuroscience supports that certain behavioral tendencies are encoded in neural circuits shared across members of a species. ↩

Anthropological studies of early human societies suggest that inter-group violence was a frequent adaptive strategy for resource competition. ↩

The emergence of agriculture and complex social hierarchies likely shifted adaptive strategies toward cooperation and alliance-building. ↩

“Entropic ordering” here refers to the structuring of cognitive tendencies over time in a way that resists chaos through patterned survival behaviors. ↩

This pragmatic orientation parallels Charles Peirce’s pragmatic maxim, in which the meaning of ideas is grounded in their conceivable practical effects. ↩

This shift marks the beginning of prospection, the capacity to simulate and evaluate possible futures before acting. ↩

This notion resonates with Henri Bergson’s idea of duration (la durée) as a qualitative, interpenetrating temporal flow. ↩

In aesthetics, contrast functions as a structuring principle—its temporal analogue is the differentiation of events to create significance. ↩

Kant- ‘the object in-itself‘

Kant explains that experience is not only the passive participation in events or the observation of objects, but also the creation or representation of them.1 He asks: Would you not call production an experience?2

For Kant, a priori knowledge simply means “universal” knowledge.3 For example, the claim that all things change involves both an a priori and an a posteriori component. Saying that a specific thing changes is not the same as explaining what change is in itself. The former refers to a determinate object undergoing change, which can only be accessed through empirical experience—by actually “looking” at it. By contrast, all things change is an a priori claim because that proposition cannot be perceived empirically or directly; any direct perception of it would mean observing only some things changing, thereby contradicting the universal claim.4

In other words, direct perception of a universal principle inevitably restricts it to a particular instance, thereby denying its universality. The notion of a priori knowledge thus concerns absolutes of pure thought. Statements such as all things change or, as Zeno inversely claims, there is no motion, are “true” only in the abstract. Abstract substance is the sole “material” that can sustain two absolute, yet logically opposite, propositions.5

A common mistake arises when the definition of an “absolute” is taken to mean that the existence of one principle necessarily excludes the existence of any other principles. This misinterpretation leads to a dead end in thought, trapping the thinker in a contradictory loop with no resolution.6

The term a priori denotes precedence over a posteriori because, in order to identify any particular object as distinct from all others, one must already possess the general concept of difference and particularity. That is, an object must have either (1) come into being through generation from some general category of being, or (2) always existed but been specifically singled out by a sensible faculty.7 For example, to pick out a triangular object undergoing changes in shape and size presupposes prior knowledge of the general concepts of shape and size—concepts that apply to all objects. One would not recognize a triangle without first understanding the universal form of triangularity.8

Similarly, to conclude that extension is a property of material objects does not require examining objects outside the one in question; the concept of extension is already contained in the nature of the object itself.9

Footnotes

Spinoza, Ethics, Part I, Proposition XV, Scholium. ↩

Kant, Critique of Pure Reason, B125–B126. ↩

Ibid., B127. ↩

Ibid., B3–B4. ↩

This is a classic example of Kant’s distinction between the universal and the particular judgment. ↩

Cf. Aristotle, Metaphysics, IV.3–4, on the principle of non-contradiction and opposites. ↩

This is a logical impasse akin to the antinomies Kant describes in the Critique of Pure Reason. ↩

Kant, Prolegomena to Any Future Metaphysics, §2–3. ↩

Plato, Meno, 81a–86c, on the recollection of forms. ↩

“fire” – atomic level

At the atomic level, from a purely physical point of view, the transformation of one element into another—say, in the combustion that produces fire—begins as a change in the motion, specifically the speed, of atoms relative to each other. Fire occurs when atoms, initially close together, begin to accelerate in relation to one another. They start to “jiggle” rapidly—this is often loosely described as “friction”¹—and eventually, with enough velocity, one atom displaces another, each occupying the space previously held by the other. This displacement triggers the release of energy: the degeneration of an atom occurs when it loses its specific position in relation to surrounding atoms, and the replacement of one atom by another automatically initiates the formation of the latter in that same position.

This process, whereby one atom rapidly replaces another, constitutes the very mechanism of deconstruction (degeneration) of any physical structure. This is why fire can consume virtually anything. At the atomic level, fire is simply a collection of atoms moving at extremely high speeds relative to one another. When such atoms encounter other atoms, they displace them—knocking them out of position—and thereby break down the structure in question. Of course, our experience of fire is not limited to this purely physical description; it possesses multidimensional aspects.

When an organism encounters this atomic process, its brain recognizes the activity and overlays sensory qualities onto it. The mind attributes the colour “red” to fire so that it can quickly draw attention when in proximity. The organism develops an instinctive intuition that fire can destroy its physical structure, followed by more elaborate perceptions and sensations—sight, smell, touch, etc. For sight, the red of fire functions as a biological warning signal. This is not because fire is inherently red—it also emits blue, violet, and even ultraviolet wavelengths²—but because the red portion of the spectrum is most salient for survival. For touch, fire produces pain because pain is the sensation associated with structural breakdown, and the organism, if it wishes to survive, should reduce contact with it.

For Kant, the question of what it means for an object to be a “thing-in-itself” (Ding an sich)³ is unanswerable, because he holds that the object is always dependent on the faculties of Reason that perceive it—the only aspect accessible to us. What the object might be outside of these faculties is unknown. This leads to his striking claim that the totality of all objects represented exists within the subjectivity of reason itself.

Kant’s philosophy culminates in the unresolved tension between the object “in itself” and the object as represented by Reason. Since the latter is always a product of reason, the question arises: does there exist an objective reality independent of Reason? Kant answers that, if such a realm exists, it is inaccessible; any representation of it would already be shaped by the categories of reason. Thus, what is “objective” for Kant coincides with what is “subjective” in the sense that both belong to the same representational domain. The distinction between the two is not one of kind, but of dimension⁴: the objective state is the totality of representations, each of which is “objective” relative to another.

The analytical faculty of understanding has two functions:

- Differentiation — distinguishing objects from one another.

- Conceptual containment — grasping an object without going beyond it to speculate about its ultimate nature.

Kant also observes that the very empirical observation of action implies that substance is not caused by anything other than itself; an action, by definition, is self-causing (causa sui).⁵ Furthermore, when a substance changes from state A to state B, the moment in which B exists is distinct from and subsequent to the moment in which A existed. This raises the question: are the two states themselves distinct from the change, or is the change simply the relation between them?

Here, we can relate this to Peirce’s “law of mind”, which holds that mind works from the future to the past, while matter works from the past to the future.⁶ In this view, the relationship between mind and matter is simultaneous: the mind’s proposal of an idea constitutes the “future” as the final cause seeking actualization, while the material process that realizes it embodies the “past” as a general substrate taking on a particular form towards actualizing it.

Footnotes:

- In physics, the rapid motion of atoms is due to increased kinetic energy; “friction” here is metaphorical, as true friction occurs between macroscopic bodies, though interatomic collisions produce similar energetic effects.

- Blackbody radiation from hot objects emits a spectrum; fire appears red or orange at lower temperatures (~600–1000°C) and shifts toward blue at higher temperatures.

- Kant, Critique of Pure Reason, A30/B45, where he introduces the notion of the Ding an sich.

- On Kant’s dimensional distinction between appearances and things-in-themselves, see Critique of Pure Reason, A235/B294.

- Kant, Metaphysical Foundations of Natural Science, §6.

- C.S. Peirce, “The Law of Mind” (1892), The Monist, Vol. 2, No. 4, pp. 533–559.

The intuition is the instinct of Reason

For Kant, intuition is indistinguishable from the principles of space and time; these principles are not merely derivedfrom intuition, but are in fact identical with it.1

If, for example, we ask: How do we derive the fundamental nature of things? The immediate answer is that sensationconfirms that there are objects of existence. Yet, when we ask about the nature of the object, sensation can only indicate the features it is capable of grasping—sound, taste, color, etc.—but all such features merely indicate that there are objects possessing these features. If we further ask: What is the relation between one object and another? Sensation can only show that they possess one feature over another, without revealing how such features constitute the same object.

This requires a faculty different from sensation—one capable of grasping the essential relations that constitute objects. The understanding, whose predicate nature is desire (and which is the highest form of desire), can analyze things by dividing their natures, yet this analytic process still requires another faculty: one that can derive the essential form and nature of objects. It is precisely this faculty that we so habitually deny exists at all—biting the very hand that feeds us, or rather, looking away from the very mode of cognition that enables us to deny it in the first place. This denial is not merely a logical fallacy, but also an ethical one, for all logical fallacies are in essence ethical errors.2

Kant argues that intuition is the faculty that grasps the fundamental relations between objects. For example, the notions of space and time are not derived from sensation, because sensation contains no such notions; in sensation, things simply exist as they are.3 Space and time are instead derived from intuition, for intuition is the faculty in which the essential nature of objects resides. If space and time are concepts of intuition, we must therefore ask: What is the nature of the intuition that always possesses these concepts, which serve as the fundamental relations binding all objects of sensation together?

This brings us back to the principle that “the relation is more fundamental than the parts.” To say that the relation is more fundamental is to say that the self-identical being is, in fact, the same determination capable of intuition in one way or another. Intuition is simply the determination of an activity.

The proof for this lies in the relationship between sensation and cognition. Do we say that sensation belongs to cognition, or cognition belongs to sensation? Aristotle poses the question: Do we see in order that we may have eyes, or do we have eyes in order that we may see?4 Even empirically, if we examine human anatomy, we find that all organs of sensation are extensions of the brain: the eyes connect to the occipital lobe, and the brain itself receives and processes all sensory information.5 It is therefore indisputable that the organs of sensation are faculties of the mind, not the other way around.

It is absurd to claim that the mind belongs to the eyes, the nose, or the ears. Yet, the foundational logic of much of empiricism rests on precisely this assumption: that the mind derives its knowledge solely from sensation. This is a crude opinion, for sensation is itself a higher-order mode of information acquisition, one that belongs to biological life. The process of reason, by contrast, extends beyond the scope of comprehension possible even to the most complex biological organisms such as the human being.6

Footnotes

Peirce’s “Law of Mind” in The Monist (1892) provides a parallel: mind works from the future to the past, while matter works from the past to the future. ↩

Kant, Critique of Pure Reason, A22/B37–A26/B42. Kant explicitly states that space and time are forms of intuition rather than derived empirical concepts. ↩

This echoes Aristotle’s view in the Nicomachean Ethics that intellectual error is inseparable from ethical failing, since the good is bound up with right reason (orthos logos). ↩

Kant, Critique of Pure Reason, A23/B38–A24/B39. ↩

Aristotle, De Anima, 415b15–20. ↩

See Bear, Connors, and Paradiso, Neuroscience: Exploring the Brain, 4th ed., on the neural pathways of sensory organs. ↩

Consciousness “I”- observe the environment

The categories outlined by Aristotle, later appropriated by Kant and Hegel, are in truth the fundamental determinations of being. They are logical because being is characterized by the concept of Reason. Reason is the manifold of consciousness. All such principles and categories are separated for analytical purposes, yet in their essential nature they belong to consciousness itself.

The ordinary understanding of consciousness is roughly as follows: it is usually stated that consciousness belongs to an “I,” and that what I am as consciousness is external to another consciousness which, from its own point of view, is also an “I” in and of itself. From my point of view, however, it is an other. Thus, the interactions between these various consciousnesses are seen as instances of one consciousness imposing its will upon another.

When one asks what constitutes the continuity between consciousnesses, the common answer is that they are in communion because they share the same environment. This answer is, however, neither satisfying nor logically adequate. If the environment is the only means of connection between opposing consciousnesses, one must ask: In what way is the environment observed? If the answer is a return to the concept of consciousness—that the environment is observed and thereby confirmed by consciousness—then a further question follows: What if the opposing consciousnesses observe the environment differently?

This assumption logically follows from the earlier claim that consciousnesses are opposed as others, for my being an “I” necessarily excludes your being the same “I”; otherwise, there would be no distinction between us. Empirically, such a distinction clearly exists, for each “I” is situated in a different body.

If opposing consciousnesses each observe the environment differently—and they do, given their distinct positions within it—under what sense, then, is the environment their shared continuity? Even granting the difference in perception, the environment still contains both opposing forms of consciousness. Empirically, there is a variety of bodies, each with a head containing a brain.

Does the fact that opposing consciousnesses hold opposing views about the environment exclude the fact that they nevertheless represent it and are contained within it? If the environment contains that which represents it, then the crucial question is: What is the relation between the representation and the environment itself? The answer must be that the opposing forms of consciousness exist within the same consciousness that contains their opposition. Indeed, the very recognition that one consciousness opposes another presupposes a consciousness they already share.1

The difficulty with Kant—one that Hegel appears to resolve—is that Kant maintains intuition and its categories as subjective determinations, such that they contain the object. Hegel, by contrast, argues that the determinations of thought are not merely subjective, for what Kant calls “subjective” is a confused way of naming that which contains the objective. Thought not only contains the object but is also contained by it; in other words, thought is the content of the object, and the object is nothing other than that in which thought partakes.2

The notion of the ultimate observer can be clarified through the concept of the infinite—analogous to the distinction between cardinal and ordinal numbers. Cardinality measures quantity; ordinality measures position within a structure. In the same way, the infinite is not merely a sum of parts but the structural whole within which those parts (finite consciousnesses) take their place.3

Footnotes

For the mathematical analogy, see Cantor’s work on transfinite numbers (Beiträge zur Begründung der transfiniten Mengenlehre, 1895–97), where ordinal and cardinal infinities represent distinct but related ways of conceiving the infinite. ↩

This is akin to Husserl’s concept of the lifeworld (Lebenswelt)—the pre-given horizon of meaning in which all subjective perspectives already coexist. ↩

See Hegel, Science of Logic, “Doctrine of the Concept,” where he rejects Kant’s separation between the form of thought and the thing-in-itself. ↩

Misinterpretation of Intuition

The intuition is the only faculty of thought whose very existence is disputed. There is no doubt that all the faculties of sensation, as well as that of the understanding, are generally accepted as the only valid modes of thought. The argument against intuition claims that there is no immediate proof of such a faculty, in contrast to the other faculties whose existence is self-evident. For example, perception affirms its own existence; touch, smell, and so on, each confirm their own operation. Even the understanding is reflexive toward itself, recognizing itself as understanding. The intuition, on the other hand, merely receives facts about the object without providing any explicit indication of itself as the faculty receiving them. The critique thus asks: How can intuition provide knowledge without first providing knowledge of itself as the source of that knowledge? How can a faculty yield cognition without our knowing that the faculty even exists?

This skepticism toward intuition is granted as a legitimate concern—but it should in no way be taken as the final word on its nature. For the very critique leveled against intuition is itself an act of intuition, insofar as it grasps the relation between a faculty and its self-knowledge without recourse to sense-experience or purely discursive reasoning.1

Ordinarily, it is said that sensation occurs first, then intuition follows, and then the understanding. On the one hand, this sequence is correct, for intuition in this sense acts as the mediation between sensation and understanding. When the senses deliver the sensible forms of objects, the rational forms are apprehended by the intuition, and the understanding then seeks to synthesize and interpret the knowledge derived from both sensation and intuition.

However, this basic description is misleading if taken to imply that intuition depends on sensation in its very nature. At most, the appearance of chronological succession is a feature of experience, not of essence.2 We have already expressed our dissatisfaction with reading the categories in purely chronological terms. Intuition is not merely present after sensation; it is present before, during, and after every faculty of thought. Intuition is the whole within which particular faculties—sensation, understanding, and others—are contained and coordinated.

The intuition is, in this respect, the instinct of reason3—the underlying condition for any faculty to affirm itself. If we ask, “How does perception confirm itself as the faculty of seeing?” the answer is not, except humorously, “by looking in a mirror,” but rather that perception possesses an intuition of itself as perception. Any faculty must first have an intuition of its own act in order to perform its function. The physical “proof” of intuition, then, lies in the very form and operation of every other faculty. In other words, the senses came out of intuition and not the other way around. The intuition is the power of mind to find form. This, however, may not be a fully satisfactory answer, because it still defines intuition only by reference to other faculties and does not provide a definition of itself. But what if its definition is precisely the manifold of mind? What if intuition is the whole of the senses working together to create an operation of mind that is more advanced than each sense taken individually?

This is precisely what intuition is: the instinct of the mind concerning abstract phenomena arising from the past and extending into the future. We can only perceive them as they pass through the present; in that moment, the forms enter the mind and then pass beyond it. More accurately, the mind, possessed by them, derives an innate understanding of their inevitable existence, then forgets the matter and is drawn back into the immediacy of the present moment.

Footnotes

Aristotle’s nous (νοῦς) in De Anima III.4–5 offers a precedent for conceiving a faculty that grasps essences directly without mediation by sensation. ↩

Kant, Critique of Pure Reason, B33–B36, discusses the immediacy of intuition as distinct from conceptual mediation, though without acknowledging that the critique of intuition implicitly exercises the very capacity it doubts. ↩

Compare Hegel, Science of Logic, where he warns against treating the logical determinations as temporal events rather than necessary moments in the self-unfolding of thought. ↩

———-

Transcendental

Apperception (Kant) and Its Relation to Peirce’s Abduction

Apperception (Kant’s term) refers to the mental process by which an individual assimilates a new idea into their existing body of ideas—a form of what might be called “fully conscious perception,” or the recognition of a unity lying beyond immediate sensation. Kant sees the forms of reason—intuition and understanding—not merely as derived principles, but as the very conditions upon which objects attain identity in our cognition.

Kant’s use of transcendental essentially functions as his version of metaphysics. He adopts this term to denote a prioriknowledge—knowledge that precedes empirical experience. While a priori literally means “from the former,” it is often mistakenly taken to imply detachment from experience. The term transcendental is similarly misunderstood, typically interpreted as referring to “some realm beyond objects.” In Kant’s usage (and comparably in Aristotle and Hegel), experience refers more broadly to both empirical and psychical phenomena. Likewise, “beyond” should not exclude the object, but indicate a deeper inquiry beneath its empirical presentation—essentially, the realm of theoretical insight.

The Latin root trans- implies movement or transformation, which echoes Kant’s intention: transcendental refers to how abstract, conceptual structures (the forms of reason) transform into the material world that is later perceived through the senses. Kant acknowledges that our sensory faculties are limited and thus we only grasp substance in a partial sense. Hegel, meanwhile, addresses this limitation by arguing that contradiction is itself a constitutive principle of substance—not a dead end, but the very mechanism of its development.⁴

Kant’s philosophical project also includes probing the nature of material idealism—the question of whether there is an external reality beyond internal representations (such as “I think”) and how that reality might relate to inner skepticism. His famous Refutation of Idealism asserts that questioning “Why?” is not a skeptical dead-end but a fundamental mechanism in the nature of change.⁵

In Kant’s framework, apperception functions as the process through which a potential form is assimilated in relation to existing actual forms. A new actual form is generated precisely by mediating between previous ones. The relation, then, is what produces new actuality.

To broaden these ideas, consider Charles Sanders Peirce’s concept of abduction: an intuitive leap that generates new hypotheses from surprising facts—it is the introduction of new explanatory insight that cannot strictly be deduced nor derived inductively from existing premises. Abduction is characterized by creativity and informed conjecture, which resonates with Kant’s notion of intuition as that faculty enabling insights beyond sense data alone.⁶

Finally, regarding thought and consciousness: Thought is the mechanism operating within the universe. One’s awareness of thought does not imply ownership—it simply reflects the necessary, self-monitoring relationship between subject and object. Self-consciousness involves a constant, indivisible relation that requires ongoing recognition of the subject–object dynamic.

Footnotes

- Apperception (Kant): Kant distinguishes transcendental apperception (the unified consciousness underlying experience) from empirical apperception (the changing sense of self) in his Critique of Pure Reason (Wikipedia, Encyclopedia).

- Peirce and Abduction: Peirce defines abduction as the inference that introduces new explanatory hypotheses, rather than following deductive or inductive patterns (iep.utm.edu, Wikipedia).

- Transcendental and A Priori: The distinction between transcendental logic (conditions of experience) and general logic further clarifies Kant’s use of these terms (Reddit, Wikipedia).

- Hegel on Contradiction: Hegel critiques Kant by arguing that contradiction is the engine of development—not a failure of reason (plato.sydney.edu.au, messagesfromspiritworld.info).

- Refutation of Idealism & Material Idealism: Kant’s argument ensures that empirical realism—belief in external objects—is compatible with transcendental idealism (Wikipedia, Reddit).

- Abduction as Creative Intuition: Abduction’s logical form allows for imaginative insight—Peirce stresses that nature is explainable and such reasoning is essential to inquiry (iep.utm.edu, Wikipedia).

#19- Metaphysical transcendence

The Subjectivity of Thought and Apperception

Kant argues that, because understanding—the faculty of thought—is finite, it can never fully grasp the universal, which is infinite. Consequently, thought is subjective by definition. However, this very limitation is precisely how consciousness enables the universal to know itself. This process is apperception: the act of particularizing universal reason so that it may conceptually conceive itself. This is metaphysical transcendence in action.

Transcendence: Developmental Stages of Conscious Reason

Transcendence can be understood as the developmental progression of consciousness and reason. Just as humans pass through stages of growth—each featuring shifts in cognitive capacity—so the cosmos itself unfolds through dialectical stages of universal reason. We engage in self-dialogue across time, and our capacity to transcend spatial and temporal limitations is an incorporeal, eternal feature of our thought.